Southern Ethiopia faces a critical public health challenge as the World Health Organization (WHO) confirms the nation’s first-ever Marburg virus outbreak. With at least nine individuals infected by this highly contagious and often fatal disease, often likened to a cousin of Ebola, the incident has triggered urgent global health alerts and significant containment efforts. This rapidly spreading viral hemorrhagic fever, for which no vaccine or approved antiviral treatment currently exists, underscores the importance of immediate action and coordinated international support.

What is Marburg Virus Disease (MVD)?

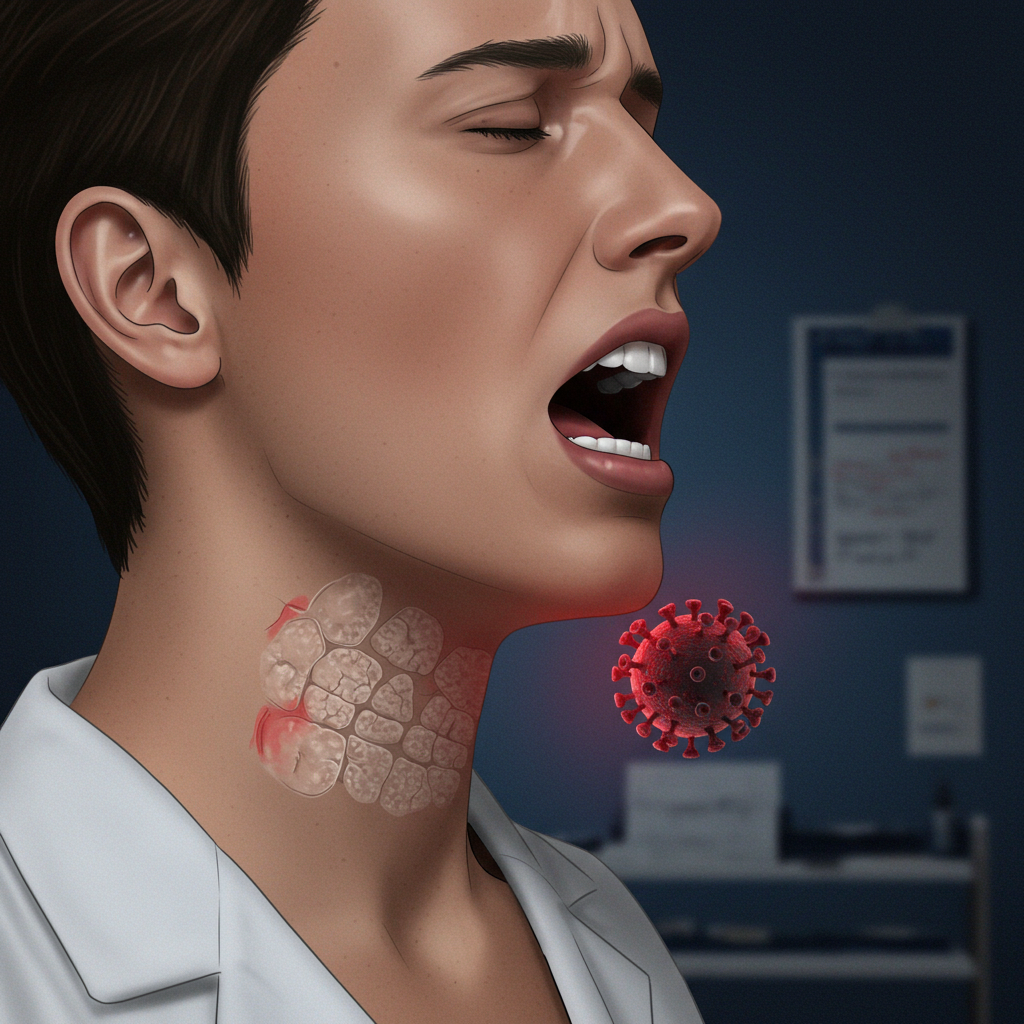

Marburg Virus Disease (MVD) is a severe viral hemorrhagic fever. It belongs to the Filoviridae family, the same classification as the Ebola virus, leading to its frequent description as “Ebola’s cousin.” Two closely related viruses, Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV), are responsible for causing MVD. These pathogens lead to severe internal bleeding and extensive organ damage, resulting in a notably high fatality rate.

The virus first emerged in 1967. This occurred following simultaneous outbreaks among laboratory workers in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany, and in Belgrade, Serbia. These initial cases were traced back to monkeys imported from Uganda. Since then, MVD has caused sporadic outbreaks across various African nations, demonstrating its concerning potential to reappear even after years of dormancy. Its classification as a zoonotic disease means it primarily transmits from animals to humans.

Ethiopia’s Urgent Battle Against the Virus

The current Marburg virus outbreak in Ethiopia marks a pivotal moment for public health in the East African country. Nine cases have been confirmed, all located in the southern region. Both the WHO and Ethiopia’s Ministry of Health have officially acknowledged the outbreak, mobilizing resources to mitigate its impact. The WHO is actively assisting Ethiopian authorities. This support focuses on containing the outbreak, providing treatment for infected individuals, and implementing strategies to prevent cross-border spread. These proactive measures are crucial given the virus’s highly contagious nature and severe outcomes.

How Marburg Virus Spreads: Understanding Transmission

The journey of the Marburg virus into human populations typically begins with a zoonotic spillover. Certain bat species, particularly fruit bats, are known natural hosts for the virus. Human infection often originates from contact with infected wild animals or their bodily fluids.

Once the virus has jumped to humans, human-to-human transmission becomes the primary driver of an outbreak. This occurs rapidly and efficiently through direct contact with the bodily fluids of infected individuals. These fluids include:

Blood

Saliva

Urine

Feces

Breast milk

Semen

Vaginal fluids

Furthermore, transmission can happen indirectly. This involves contact with surfaces and materials contaminated with these fluids. Shared items, medical equipment, and bedding can all serve as vectors for spread. Such indirect routes significantly complicate outbreak control. This highlights the critical need for immediate patient isolation and rigorous hygiene protocols in affected areas.

The Incubation Period and Early Warning Signs

After exposure, Marburg virus disease symptoms typically appear abruptly. The incubation period, which is the time from infection to symptom onset, can range from 2 to 21 days. Early signs of the illness often resemble common tropical diseases, making initial diagnosis challenging. These initial symptoms commonly include:

High fever

Severe headache

Muscle aches

Chills

Marburg Virus Symptoms: A Rapidly Progressing Illness

As MVD progresses, patients often experience a rapid worsening of their condition. Within a few days, additional severe symptoms may develop. These can include:

Chest pain or abdominal pain

Nausea

Vomiting

Intense diarrhea (which can persist for a week)

A distinctive non-itchy rash may also appear between two to seven days after the onset of initial symptoms. In advanced stages, the disease escalates to severe manifestations, including significant internal and external bleeding. Patients may experience:

Bleeding from gums, nose, and other organs

Severe blood loss

Hemorrhaging

Multi-organ dysfunction or failure

Circulatory collapse leading to shock

Fatal cases typically occur rapidly, often between eight and nine days after symptoms begin. These deaths are usually preceded by massive blood loss and severe shock. The World Health Organization estimates the average case fatality rate for MVD to be roughly 50 percent, although this figure can fluctuate significantly depending on the specific outbreak and the quality of available medical care.

Diagnosing a Complex Viral Threat

Diagnosing Marburg virus disease in its early stages is particularly challenging. Its initial symptoms mimic many other tropical diseases, such as malaria, typhoid fever, and other viral hemorrhagic fevers. Accurate diagnosis requires specialized laboratory testing of blood samples. Advanced diagnostic methods are crucial for confirming an infection, including:

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays: To detect viral genetic material.

Antibody-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA): To identify the body’s immune response to the virus.

Antigen-capture detection tests: To find viral proteins.

These specialized tests are essential for confirming MVD and enabling prompt isolation and treatment, which are vital for containing an outbreak.

Treatment and Global Efforts Against Marburg

Currently, there are no approved antiviral treatments or vaccines specifically developed to target the Marburg virus. This absence of specific therapeutic options underscores the critical nature of outbreaks and the challenges in managing infected individuals.

Patient survival largely depends on early and intensive medical intervention centered around supportive care. This comprehensive approach aims to manage symptoms and support vital bodily functions. Key aspects of supportive care include:

Aggressive rehydration: Replenishing fluids intravenously to combat dehydration caused by vomiting and diarrhea.

Restoring electrolyte balance: Correcting imbalances that can arise from severe fluid loss.

Managing bleeding: Addressing hemorrhage through blood transfusions and other interventions.

Treating any secondary infections: Administering antibiotics or other treatments for co-occurring bacterial or fungal infections.

Research efforts are actively underway to develop potential treatments and vaccines. Scientists are exploring monoclonal antibody treatments, novel antiviral compounds, and various vaccine candidates. However, none of these have yet received approval for public use. The rarity and severity of Marburg outbreaks, combined with the lack of specific therapeutic options, make the current situation in Ethiopia a matter of urgent global attention.

A History of Outbreaks: Learning from the Past

While the Ethiopia Marburg outbreak is its first, the virus has a documented history of emergence in other African nations. Previous outbreaks have been reported in:

Angola

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

Ghana

Kenya

Equatorial Guinea

Rwanda

South Africa

Tanzania

Uganda

Laboratory tests have confirmed that the strain of the Marburg virus identified in Ethiopia is consistent with those reported in previous outbreaks across East Africa. This historical pattern highlights the virus’s inherent potential to re-emerge repeatedly, even after an initial outbreak has been successfully contained. Understanding these past events is crucial for developing effective response strategies.

Containing the Spread: A Coordinated Public Health Response

Containing a Marburg virus outbreak demands an immediate, multi-faceted, and highly coordinated public health response. The WHO, in close collaboration with Ethiopian authorities, is actively implementing a comprehensive strategy. This strategy focuses on several key pillars:

Surveillance and Contact Tracing: Rapidly identifying all individuals who may have come into contact with confirmed cases to monitor for symptoms and prevent further spread.

Case Management: Providing immediate and intensive supportive care to infected patients to improve survival rates and reduce the risk of transmission.

Infection Prevention and Control (IPC): Implementing stringent hygiene protocols in healthcare settings and communities. This includes proper handling of bodily fluids, safe burial practices, and personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers.

Community Engagement: Educating local communities about the virus, its transmission, symptoms, and the importance of seeking early medical attention. This helps to build trust and encourage adherence to public health measures.

Cross-Border Preparedness: Monitoring and strengthening surveillance in neighboring regions to address the potential for international spread, a critical aspect given the disease’s high transmissibility.

The challenge of controlling such outbreaks is amplified in resource-limited settings. Swift deployment of medical supplies, trained personnel, and robust infrastructure for isolation and testing are paramount. Without immediate isolation and rigorous hygiene interventions, controlling the rapid spread of MVD becomes significantly more difficult.

Why Global Vigilance is Paramount

The Marburg virus outbreak in Ethiopia, though currently contained to a specific region, demands close global attention. The virus’s rarity, coupled with its severe clinical course and the lack of specific treatments, makes every outbreak a significant concern for global health security. The potential for the virus to mutate or spread unchecked poses a broader threat. Continued international collaboration, research into vaccines and treatments, and robust public health infrastructure in vulnerable regions are essential to prevent future outbreaks from escalating into larger crises.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Marburg virus and how does it compare to Ebola?

The Marburg virus causes Marburg Virus Disease (MVD), a severe viral hemorrhagic fever. It belongs to the same Filoviridae* family as Ebola, leading to its description as “Ebola’s cousin.” Both viruses cause similar severe symptoms like fever, bleeding, and organ damage, and have high fatality rates. Key similarities include transmission via bodily fluids and zoonotic origins (bats). However, they are distinct viruses with different genetic makeups. Currently, neither has an approved vaccine or specific antiviral treatment, though research is ongoing for both.

Where has the Marburg virus been reported before the Ethiopia outbreak?

Before the current outbreak in Ethiopia, the Marburg virus has caused sporadic outbreaks in several other African countries. These include Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ghana, Kenya, Equatorial Guinea, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda. The virus was first identified in 1967 in Germany and Serbia, linked to infected monkeys from Uganda. Ethiopia’s current outbreak is its first, and lab tests confirm the strain is consistent with previous East African outbreaks, highlighting its recurrent nature.

What are the immediate public health actions taken during a Marburg outbreak?

During a Marburg outbreak, immediate public health actions focus on rapid containment and patient care. These include: isolating confirmed cases to prevent further transmission, initiating aggressive contact tracing to monitor exposed individuals, implementing strict infection prevention and control (IPC) measures in healthcare settings, and practicing safe burial procedures. The World Health Organization also supports affected countries with resources for patient treatment (supportive care), community engagement, and cross-border surveillance to prevent the virus from spreading to neighboring regions.

Conclusion: Remaining Alert and Informed

The Marburg virus outbreak in Ethiopia represents a grave challenge requiring a swift and coordinated response. Its designation as “Ebola’s cousin” is well-earned, given its severe nature and high fatality rate, further compounded by the current absence of specific treatments or vaccines. The concerted efforts of the WHO and Ethiopian authorities are vital for containing this first-time outbreak and protecting communities. As global health experts continue to monitor the situation, staying informed and adhering to public health guidelines remains crucial for both affected regions and the international community.