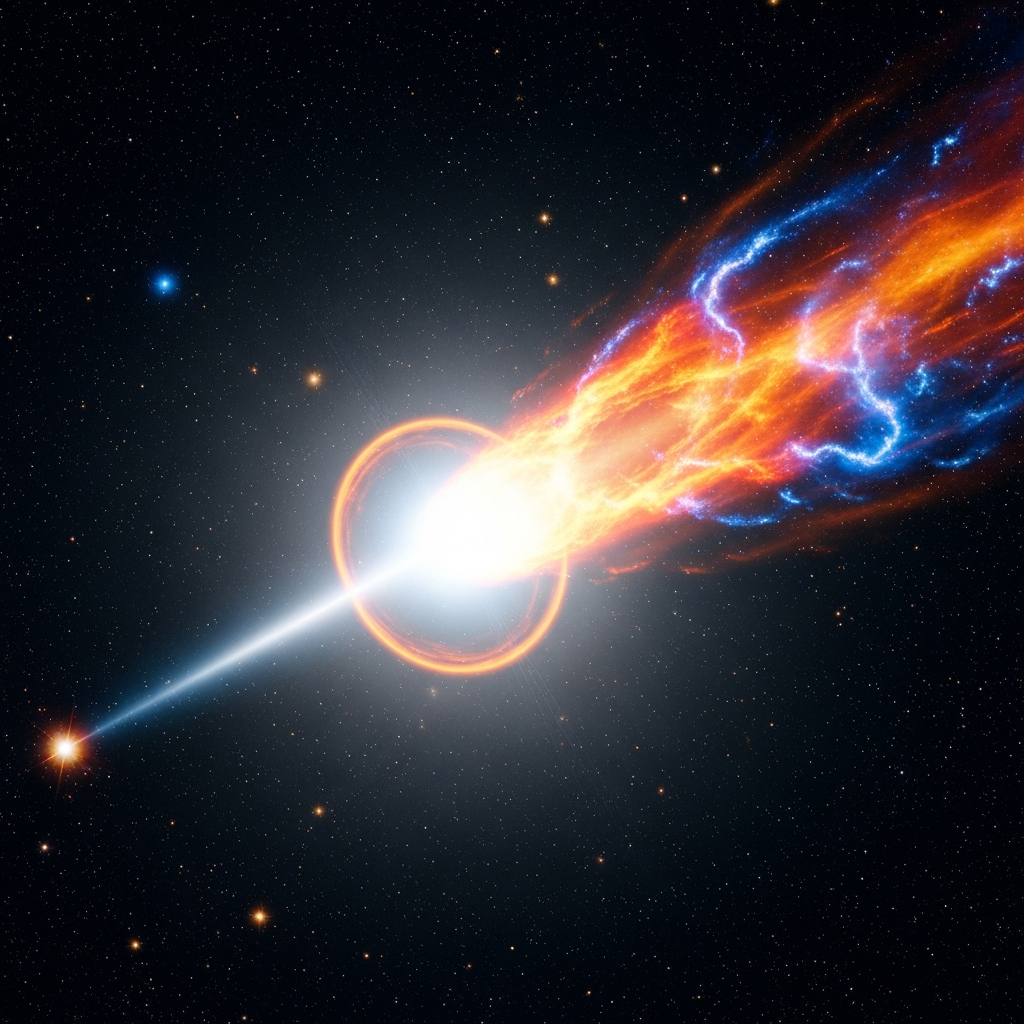

The cosmos frequently delivers breathtaking spectacles, but some events challenge our deepest understanding of the universe. One such phenomenon is GRB 250702B, a record-shattering gamma-ray burst detected on July 2nd, 2025. This colossal stellar explosion blazed for an unprecedented seven hours, nearly doubling the duration of any previously recorded gamma-ray burst. Far from being a mere anomaly, GRB 250702B has become a profound “cosmic stress test” for astrophysical models, forcing scientists to rethink how the most energetic events in the universe are born. Its puzzling characteristics, from unusual X-ray patterns to an unexpected host galaxy, demand a fresh look at the extreme physics of black holes and dying stars.

The Unprecedented Seven-Hour Cosmic Blast

Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are the most luminous and energetic explosions in the cosmos. These fleeting flashes typically last just milliseconds, or at most a few minutes. Even the handful that extend for hours are rare outliers. With over 15,000 GRBs detected to date, astronomers thought they had a firm grasp on these powerful events. Then came GRB 250702B.

Lasting a staggering seven hours, this gamma-ray burst defied all expectations. Its extraordinary duration meant no single space-based instrument could continuously observe it. Eric Burns, an astrophysicist at Louisiana State University, highlighted the observational challenge: “The burst went on for so long that no high-energy monitor in space was equipped to fully observe it.” Only through the synchronized efforts of multiple spacecraft and ground-based telescopes could researchers piece together its story. As Brendan O’Connor and his team observed, GRB 250702B “does not neatly fit into any class of known high-energy transients.” This single event underscores the vast uncertainties that still surround the causes of these cosmic leviathans.

A Multi-Telescope Pursuit Across Billions of Light-Years

Unraveling the mystery of GRB 250702B required a truly global and multi-wavelength astronomical campaign. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope made the initial detection, triggering a rapid follow-up from a constellation of instruments. X-ray observatories like NASA’s Swift, Chandra, and NuSTAR quickly pinpointed its location. Ground-based giants, including the Keck, Gemini, and Very Large Telescope (VLT), gathered crucial optical and infrared data.

Andrew Levan, an astrophysics professor at Radboud University, described the distant host galaxy as “strange looking.” The Hubble Space Telescope later confirmed this and helped to clarify its structure. High-resolution imagery from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) with its NIRCam instrument allowed Huei Sears of Rutgers University to see the burst shining through a prominent dust lane. Later, Benjamin Gompertz’s team, using JWST’s NIRSpec and the VLT, determined the burst’s incredible power. It erupted with energy equivalent to a thousand Suns shining for ten billion years. This gamma-ray burst was also remarkably ancient, originating about 8 billion years ago—long before our own Sun and solar system even existed.

Jonathan Carney, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina, led an extensive ground campaign using the NSF Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope and the twin 8.1-meter International Gemini Observatory telescopes. These rapid-pointing instruments were crucial for capturing the fading afterglow. The combined efforts of these observatories revealed a dense, dusty environment surrounding the GRB 250702B source. This heavy obscuration, primarily within the host galaxy itself, explained why the afterglow was almost invisible in visible light but shone brightly in infrared wavelengths.

Unpacking the Anomalies: Why GRB 250702B Defies Standard Models

Most long-duration GRBs are linked to the catastrophic collapse of massive stars into black holes—events known as supernovae. These typically feature a sharp initial blast of gamma-rays, followed by a gradually fading afterglow of X-rays and other emissions over several days. However, GRB 250702B presented a suite of peculiar characteristics that don’t fit the standard picture.

Firstly, its X-ray emissions were far more complex. While typical GRBs produce a declining afterglow, GRB 250702B exhibited rapid, repeating X-ray flares up to two days after the main burst. Brendan O’Connor of Carnegie Mellon University explains, “The late X-ray flares show us that the blast’s power source refused to shut off, which means the black hole kept feeding for at least a few days after the initial eruption.” This implies a sustained accretion of matter onto a black hole, powering these prolonged flares.

Even more intriguing, the event displayed clear signs of X-ray emissions preceding the main gamma-ray burst. This crucial clue suggests material was accumulating and heating up in an accretion disk around a compact object before the main explosion.

Lastly, the host galaxy of GRB 250702B itself is an anomaly. Most GRBs occur in smaller, often irregular galaxies. Yet, Jonathan Carney’s detailed study revealed that this host galaxy is surprisingly massive, “with more than twice the mass of our own galaxy.” JWST observations ruled out the galaxy’s central supermassive black hole as the source. These combined features—extended duration, pre- and post-burst X-ray activity, and a massive, dusty host—paint the picture of a truly unique cosmic event.

Leading Theories: Unmasking the “Novel Progenitor”

Given its extraordinary properties, astronomers have proposed several novel scenarios to explain GRB 250702B, largely centering on different types of black holes consuming stellar material. These are primarily variations of Tidal Disruption Events (TDEs), where a black hole’s gravity tears a star apart.

Scenario 1: The Elusive Intermediate-Mass Black Hole (IMBH) Tidal Disruption

One of the most tantalizing possibilities involves an intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH). These elusive objects, weighing a few thousand to hundreds of thousands of solar masses, are theorized to exist between stellar-mass black holes and supermassive ones, but direct evidence of their activity is rare. In this scenario, an IMBH tidally disrupts a star that wanders too close, stretching it into a stream of material before rapidly absorbing it. This process creates an accretion disk and launches a powerful, relativistic jet. If confirmed, GRB 250702B would mark the first direct observation of a relativistic jet from a feeding IMBH, providing critical insight into this mysterious class of black holes.

Scenario 2: A Stellar Black Hole Consuming its Companion

Another compelling explanation involves a stellar-mass black hole, around three times the mass of our Sun, in a binary system with a companion star. In this specific model, the companion is a hydrogen-stripped helium star, smaller than the Sun but with a similar mass to the black hole. The black hole is believed to fall into the helium star, rapidly consuming it from within. This rapid ingestion would trigger the intense gamma-ray burst. This scenario would likely also produce a supernova explosion. However, no supernova was detected, possibly due to the dense dust within the host galaxy, which would effectively obscure such an event even from the powerful gaze of the JWST.

Other possibilities include an unusual stellar collapse, where a black hole forms inside a hydrogen-stripped, helium-rich star and launches a long-lived jet (a variation of the second scenario), or a “micro-tidal disruption event” where a smaller celestial body, like a brown dwarf or even a planet, is shredded by a compact remnant. In all TDE-like scenarios, the process begins with matter forming a hot accretion disk around the black hole, explaining the observed pre-GRB X-ray emissions. The rapid engulfment of the star then fuels the main gamma-ray burst.

The Future of Ultra-Long GRB Research

GRB 250702B has dramatically expanded our understanding of extreme cosmic events. It serves as a vital “cosmic stress test,” pushing theoretical models of jet production, energy extraction, and disk accretion to account for durations spanning hours instead of mere seconds. The heavy dust obscuration encountered by astronomers also highlights the critical importance of infrared observations and persistent follow-up to detect and characterize similar ultra-long gamma-ray bursts that might otherwise remain hidden in the dusty corners of the universe.

The unusual massiveness of its host galaxy further expands our demographic map of where such powerful jets can be born. While the precise cause of GRB 250702B remains an ongoing puzzle, as Carney and his co-authors conclude, its “multiwavelength signatures… make it a unique puzzle that may originate from a novel progenitor.” Future research will involve late-time infrared imaging to search for any delayed supernova signatures, deep radio monitoring to track the jet’s energy, and spectroscopy to refine the host galaxy’s properties. Scientists are also actively searching for more “cousins” in this fascinating family of ultra-long GRBs, embarking on what Jonathan Carney aptly describes as a “fascinating cosmic archaeology problem.”

Frequently Asked Questions

What made GRB 250702B so unique compared to other gamma-ray bursts?

GRB 250702B stands out for several reasons. Primarily, its seven-hour duration nearly doubled the previous record for a gamma-ray burst, challenging existing classification models. It also exhibited unusual X-ray activity, including significant emissions before the main burst and rapid, repeating flares up to two days after. Furthermore, its host galaxy was exceptionally massive, more than twice the size of the Milky Way, and heavily obscured by dust, unlike typical GRB environments. These combined features suggest a unique and powerful cosmic engine at play.

Which telescopes were crucial in observing and understanding GRB 250702B?

Understanding GRB 250702B required a massive international effort across various wavelengths. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected the initial burst. X-ray observatories like Swift, Chandra, and NuSTAR tracked its X-ray emissions. Ground-based telescopes such as the Keck Observatory, Gemini Observatory, VLT (Very Large Telescope), and the NSF Víctor M. Blanco Telescope gathered optical and infrared data. The Hubble Space Telescope and particularly the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) provided unprecedented detail on the host galaxy and the dust obscuration.

What are the leading theories for the origin of GRB 250702B, and why are they still uncertain?

The two leading theories involve a black hole consuming a star in a Tidal Disruption Event (TDE). One scenario proposes an elusive intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH) shredding a nearby star, potentially marking the first direct observation of a jet from such an object. The other suggests a stellar-mass black hole in a binary system falling into and consuming its companion helium star. Both scenarios can explain the prolonged activity and pre-burst X-rays via an accretion disk. Uncertainty persists because neither perfectly accounts for all observed features—like the absence of a supernova in the second scenario (possibly hidden by dust), or the rarity of IMBH jet observations—making GRB 250702B a complex puzzle awaiting further data.

Conclusion

The detection of GRB 250702B has opened an exhilarating new chapter in high-energy astrophysics. This seven-hour cosmic explosion, an unprecedented event, serves as a powerful reminder of the universe’s capacity for unexpected phenomena. While its ultimate origin remains an enthralling mystery, the multi-faceted observations and cutting-edge theoretical work are pushing the boundaries of our knowledge. As scientists continue to pore over its data and hunt for similar “ultra-long” gamma-ray bursts, GRB 250702B will undoubtedly inspire new models and deepen our understanding of the most extreme engines in the cosmos. The journey to unravel its secrets has only just begun.