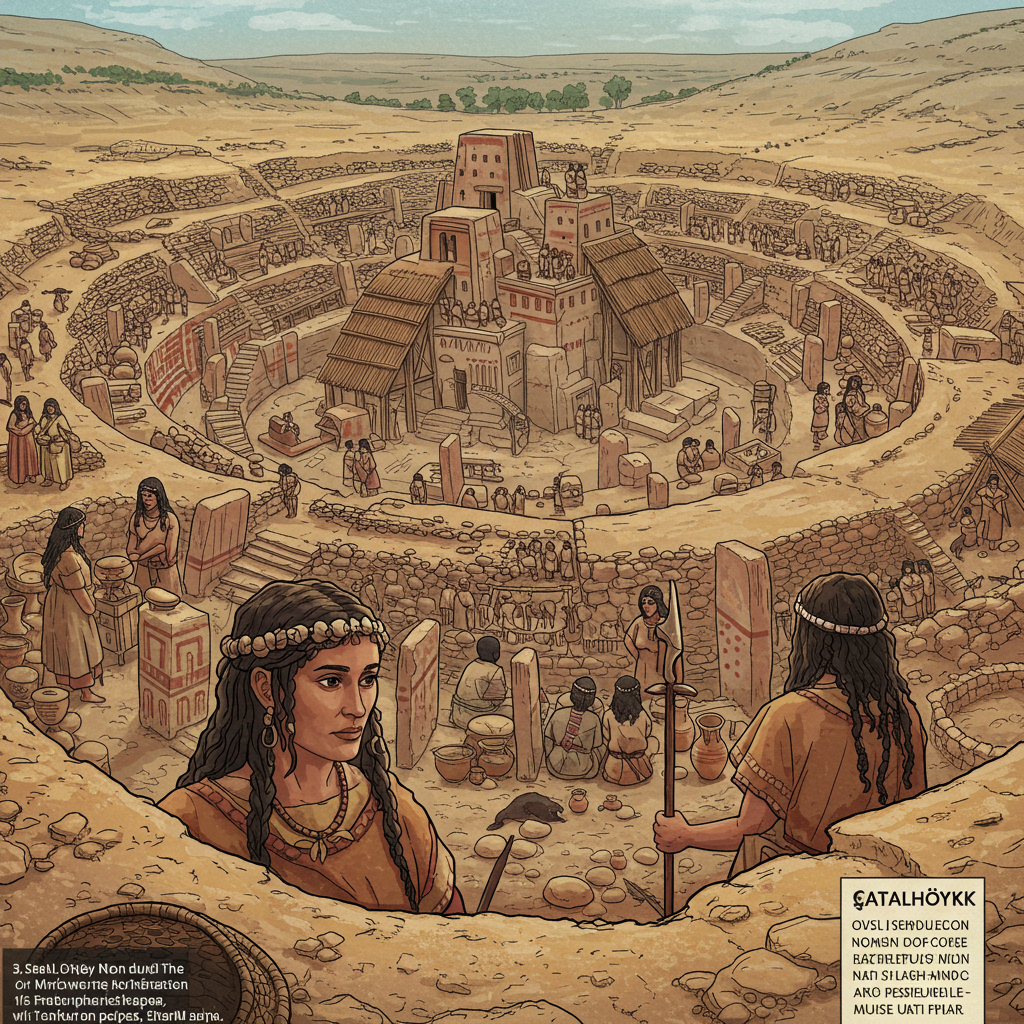

The remains of an ancient city in what is now Turkey are yielding powerful new insights into how some of the earliest human settlements were organized. For years, archaeological evidence from the sprawling Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük has hinted at a unique social structure. Now, groundbreaking genetic research adds a compelling layer, suggesting this bustling community, which thrived over 9,000 years ago, may have been centered around females in ways previously underestimated.

This challenges long-held assumptions that ancient societies were universally dominated by men. Scientists analyzing DNA from skeletons buried beneath the floors of Çatalhöyük’s distinctive mudbrick houses have found strong evidence pointing to female lineage and presence playing a central role in household identity and continuity across generations.

Unearthing Çatalhöyük’s Secrets

Located in southern Anatolia, Çatalhöyük is considered one of the most significant and well-preserved Neolithic settlements discovered. Occupied for more than a thousand years, from roughly 7100 to 5800 BCE, it wasn’t a simple village but a large, dense proto-city. Its inhabitants lived in interconnected houses with rooftop access, practiced early agriculture, and left behind a rich archaeological record.

Among the most intriguing finds were numerous female figurines, leading some early archaeologists, like James Mellaart in the 1960s, to speculate about a potential “Mother Goddess” cult and a matriarchal society. Later research, notably under Ian Hodder, moved towards interpreting the society as more egalitarian, questioning the matriarchy hypothesis. This new study aimed to use cutting-edge ancient DNA analysis to provide concrete data about relatedness and social organization within the site.

A multidisciplinary team comprising geneticists, archaeologists, and biological anthropologists spent over a decade analyzing the ancient genomes. They extracted DNA from more than 130 skeletons found within 35 different houses. Over the occupation period, roughly 395 individuals in total, a mix of males and females, were interred in pits dug beneath the very floors where daily life took place.

Genetic Clues to Social Structure

The in-depth genetic sequencing revealed fascinating patterns of kinship and residence. Researchers connected 109 individuals across 31 buildings through their DNA. Within a single building, first-degree relatives like parents, children, and siblings were consistently buried together. Second and third-degree relatives, such as aunts, uncles, grandparents, and cousins, were often found buried in nearby buildings, indicating a community structure based around extended kinship networks.

Crucially, the study identified a compelling trend regarding intergenerational connections within houses. These links were based primarily on maternal lineages. While early in Çatalhöyük’s history, burials often included multiple genetically related individuals, later periods saw a mix of unrelated people interred together. However, when a genetic connection was present across generations within a building, it was frequently traceable through the female line.

This pattern strongly suggests a practice known as matrilocal residence. Rather than wives moving to live with their husband’s family upon marriage (patrilocal residence, common in many historical and modern societies), evidence from Çatalhöyük suggests husbands likely relocated to live with their wife’s household. Genetic estimates indicated that between 70% and 100% of female offspring remained connected to their original households over time, whereas adult male offspring were more likely to move away.

Preferential Treatment in Burial

Beyond residence patterns, the study uncovered significant evidence of differential treatment based on sex, particularly visible in burial practices. The analysis showed a clear pattern of preferential treatment towards females.

Findings indicated that grave goods – items buried with the deceased – were offered significantly more often to females than to males. The study found females received grave goods at a rate roughly five times higher than males. This disparity was even observed in the burials of very young individuals; using DNA to determine the biological sex of infants and young children (otherwise difficult from skeletal remains), researchers found that female babies were buried with more grave gifts than male babies. This suggests that female importance or status was recognized from a very early age in Çatalhöyük society.

Challenging Western Bias and Historical Narratives

These findings from Çatalhöyük carry profound implications for how we understand ancient human social organization. They directly challenge the common assumption, often influenced by Western cultural biases, that patrilineal and patriarchal systems were the default or universal structure for ancient societies.

As study co-author Dr. Eline Schotsmans noted, “We need to move away from our Western bias that assumes all societies are patrilineal.” Many diverse cultures, including some Indigenous Australian groups, historically and currently pass identity, land rights, and responsibilities through the mother’s line—a matrilineal system. Çatalhöyük provides compelling early evidence for such a system in a sedentary agricultural community.

The Çatalhöyük study also resonates with recent research on ancient Celtic societies in Britain before the Roman invasion. A study published in Nature analyzing ancient DNA from a late Iron Age cemetery in Dorset, southwest England, found women were closely related within the community, while men tended to move in from elsewhere, likely through marriage. Two-thirds of the individuals analyzed were descended from a single maternal lineage, suggesting women may have had significant control over land, property, and social support networks, with maternal ancestry potentially shaping group identities. These parallels suggest female-centered social structures may have been more widespread in history than previously thought.

Furthermore, the Çatalhöyük findings contribute to the broader debate about the origins of patriarchy. They provide archaeological evidence of a complex, sedentary, food-producing society that existed without clear gender role distinctions in diet or height, and where female lineage was central. This challenges hypotheses that patriarchy was an inevitable biological outcome or solely driven by the advent of agriculture due to men’s physical strength. Instead, it lends support to theories suggesting that dominant male power structures were later societal impositions, potentially driven by elite interests in warfare and population growth, rather than inherent or universal human behavior.

What “Female-Centered” Might Mean

While the term “matriarchal” (rule by women) is often debated and difficult to definitively prove archaeologically, the researchers carefully describe Çatalhöyük’s structure as “female-centered.” This emphasizes the significance of female lineage, presence, and potential influence within the household and community without necessarily asserting formal political rule by women.

The evidence strongly points to women and girls holding key positions within this ancient agricultural society. Matrilocal residence would have meant women remained within their kin networks throughout their lives, potentially wielding significant influence within the household and community decision-making. Their lineage provided continuity for the household and the collective identity of those buried within the buildings. The preferential burial treatment further underscores a higher value or status placed upon females in this society compared to males.

Looking Ahead: Future Research

The researchers view this comprehensive genetic analysis of Çatalhöyük skeletons as a crucial first step. A significant next step involves expanding this type of ancient DNA analysis to even earlier societies in the region. This would help determine whether Çatalhöyük’s female-centered structure was a unique local development or part of a broader pattern of social organization in early Neolithic communities before the widespread adoption of patrilineal systems seen later in many parts of Europe and Asia.

The study definitively confirms previous suspicions that women played vital roles in this ancient proto-city. It provides compelling scientific evidence that forces us to re-evaluate our understanding of gender roles, power dynamics, and social structures in the distant past.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the key finding about social structure at ancient Çatalhöyük?

The primary finding, based on ancient DNA analysis of skeletons buried under house floors, is that maternal lineage played a crucial role in connecting household members across generations at Çatalhöyük, Turkey, over 9,000 years ago. Genetic evidence suggests a pattern of matrilocal residence, where females tended to remain in their original households, while males were more likely to move, possibly upon marriage.

What specific evidence supports the idea of female importance in Çatalhöyük?

Several lines of evidence from the study support the idea of significant female importance. The genetic analysis showing maternal lineage as the primary connector within households points to women as central figures for kinship and continuity. The pattern of matrilocal residence means women remained anchored within their familial and community networks. Furthermore, the finding that females, including female infants, were buried with significantly more grave goods than males suggests a higher social status or value placed upon them.

How do the findings from Çatalhöyük challenge common assumptions about ancient societies?

The Çatalhöyük findings challenge the widespread assumption that ancient societies were universally patrilineal or patriarchal (male-dominated). By demonstrating a community structured around female lineage and potentially featuring matrilocal residence and preferential treatment for females in burial, this research provides compelling counter-evidence. It suggests that diverse social structures existed in prehistory, including those where females held central and influential positions, reshaping our understanding of gender roles in early human history.

The study of ancient Çatalhöyük, through the lens of cutting-edge genetic science, provides a vivid picture of a past society where women and female lineage were central pillars of community structure and identity. It serves as a powerful reminder to question conventional narratives about gender roles throughout history and to appreciate the rich diversity of human social organization across time and cultures. This research significantly reshapes our perspective on the potential influence and status held by women in some of the earliest complex human settlements.

Word Count Check: 1152