When Steven Spielberg’s Jaws began filming on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, in 1974, few could predict the cinematic phenomenon it would become. By all accounts, the production was a nightmare, plagued by technical failures, relentless delays, and an ambitious young director navigating the treacherous waters of big-budget filmmaking for the first time. Yet, from this chaos emerged a masterpiece that not only terrified audiences but fundamentally changed Hollywood forever.

A Production Plagued by Problems

The core of the Jaws production woes lay with its mechanical star: the malfunctioning shark, affectionately nicknamed “Bruce.” Designed to bring the massive Great White to terrifying life, the animatronic figure was a constant source of frustration. While tested in a tank, it hadn’t been tested in saltwater, leading to frequent breakdowns that brought filming to a standstill. This technical hurdle, combined with the inherent difficulties of shooting on the open ocean off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard (which served as the fictional Amity Island), pushed the production well over schedule and significantly over budget.

Director Steven Spielberg, then just 26 or 27 years old, was relatively new to feature films. He later revealed that the sheer scale and difficulty of the seven or eight months spent shooting on location left him feeling completely overwhelmed – “in it, shall I say, over my head.” The weight of responsibility for the entire crew and the extended schedule took a significant psychological toll. Upon wrapping principal photography on Martha’s Vineyard, Spielberg suffered a severe panic attack, experiencing symptoms like difficulty breathing, shaking, and disorientation. He has since described the Jaws experience as the most challenging logistical undertaking of his career, a “life-altering” and “traumatizing” survival experience that left him with nightmares for years afterward.

The demanding environment also strained relationships among the human cast. While Roy Scheider (Chief Brody) and Richard Dreyfuss (Matt Hooper) were joined by veteran actor Robert Shaw (Quint), the interactions between Dreyfuss and Shaw were reportedly tense. Spielberg frequently noted a dynamic between them that mirrored their characters’ onscreen rivalry. Shaw, grappling with personal issues, was said to frequently mock Dreyfuss, though Dreyfuss later denied a genuine “feud” occurred, suggesting any digs were merely attempts to make the long hours on set pass quicker, without lasting animosity. This behind-the-scenes friction was so significant it inspired a play, The Shark Is Broken, written by Robert Shaw’s son, focusing on the difficulties and cast dynamics during the shoot.

Bringing Amity Island to Life

Despite the challenges, Martha’s Vineyard proved a compelling stand-in for Amity Island. Many island locations became instantly recognizable in the film:

Beaches: South Beach in Edgartown hosted iconic scenes like the opening party, while Joseph A Sylvia State Beach in Oak Bluffs was where the raft attack occurred.

Waterways: The American Legion Memorial Bridge near Sylvia State Beach is seen as the shark enters Sengekontacket Pond.

Town Settings: Edgartown Town Hall served as the film’s town hall, and the junction of Water and Main streets in Edgartown was used for scenes like Chief Brody getting materials for signs.

Residences: The Brody House is located on East Chop Drive in Vineyard Haven.

Harbor Areas: The ferry launch at the end of Daggett Street in Edgartown was featured in scenes involving the Mayor and Chief Brody.

Remarkably, actress Lorraine Gary noted that almost everything seen in the film was already present on the island, aside from Quint’s iconic shack. Even the production office in Edgartown doubled as Chief Brody’s police station in the movie.

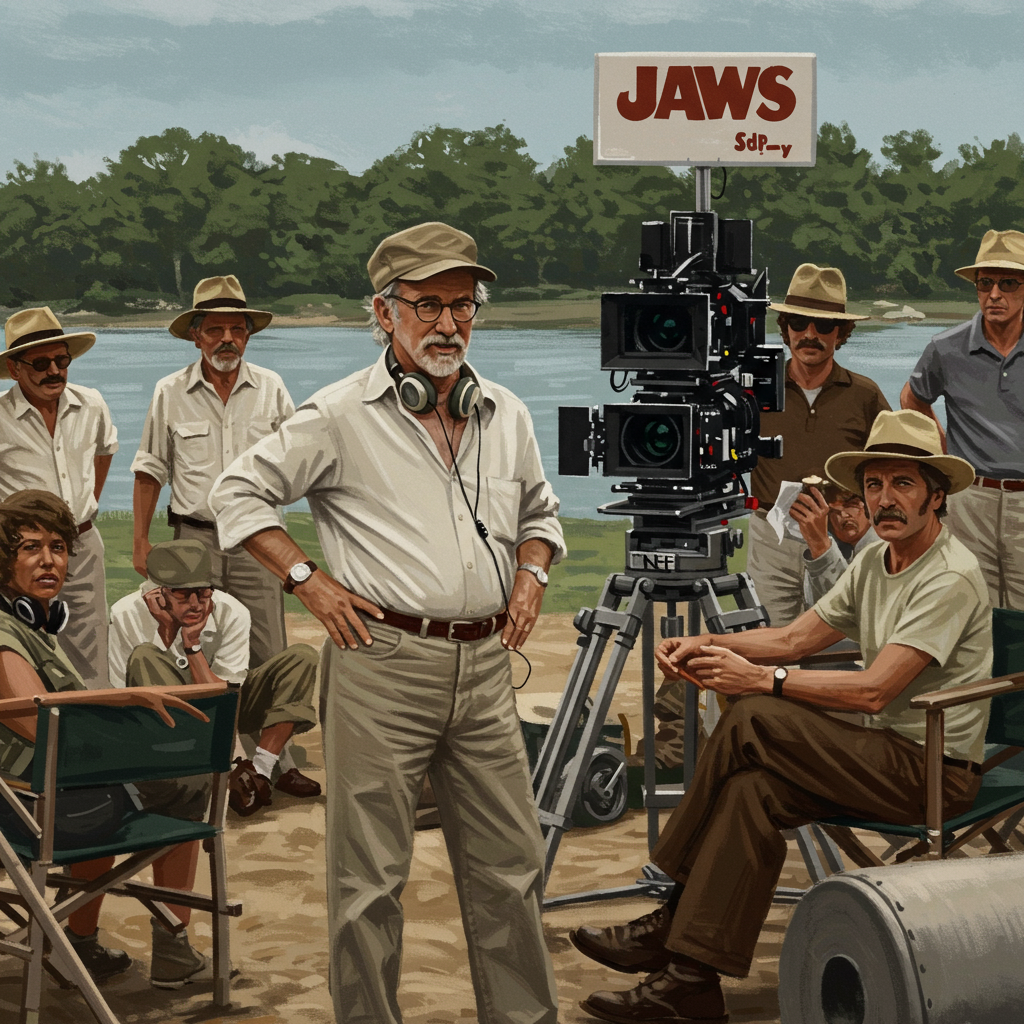

Rare Glimpses Behind the Camera

The demanding production was captured by various photographers, offering fascinating glimpses into the struggle and camaraderie on set. Recently, rare, previously unpublished photos taken by photojournalist Peter Vandermark in 1974 resurfaced. Working for a local newspaper at the time, Vandermark had unexpected access to the set for a day, capturing the cast and crew, including a young Spielberg, navigating the difficult Orca pursuit scenes at sea. While his assignment was to document the filmmaking, Vandermark felt the photos truly telling the story were those capturing the informal moments – the cast and crew “hanging out, reading, chatting, and joking around” between takes. These images, along with others from the tumultuous shoot, reveal the human side of a production pushed to its limits.

From Troubled Shoot to Timeless Classic

Against all odds, Jaws defied its troubled birth. Released in 1975, it became the highest-grossing film ever at the time, pioneering the concept of the “summer blockbuster.” The mechanical shark’s failure inadvertently contributed to the film’s success, forcing Spielberg to rely on implication, suggestion, and John Williams’ iconic, pulse-pounding score to build suspense – a far more terrifying approach than simply showing the creature.

The film earned critical acclaim, nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards and winning three Oscars for Best Sound, Best Film Editing, and Best Original Score. Its masterful control of tension continues to influence filmmakers today.

Fifty years later, Jaws remains a cinematic landmark. Its tumultuous production is legendary, a testament to the perseverance of a determined cast and crew, led by a young director under immense pressure. As Spielberg himself reflected decades later, they “survived something significant,” creating a film whose enduring success is a badge of honor for everyone involved. Commemorations, including events on Martha’s Vineyard and projects like the Jaws @ 50* documentary and the publishing of rare production photos, continue to celebrate the enduring legacy of this accidental classic.