In the dark, crushing depths of the ocean, a surprising discovery is changing our understanding of how life survives without sunlight. Scientists have recently found several new species of sea spiders that appear to defy typical biology, thriving not on conventional prey, but on methane – the very gas known for its warming effect on Earth’s atmosphere.

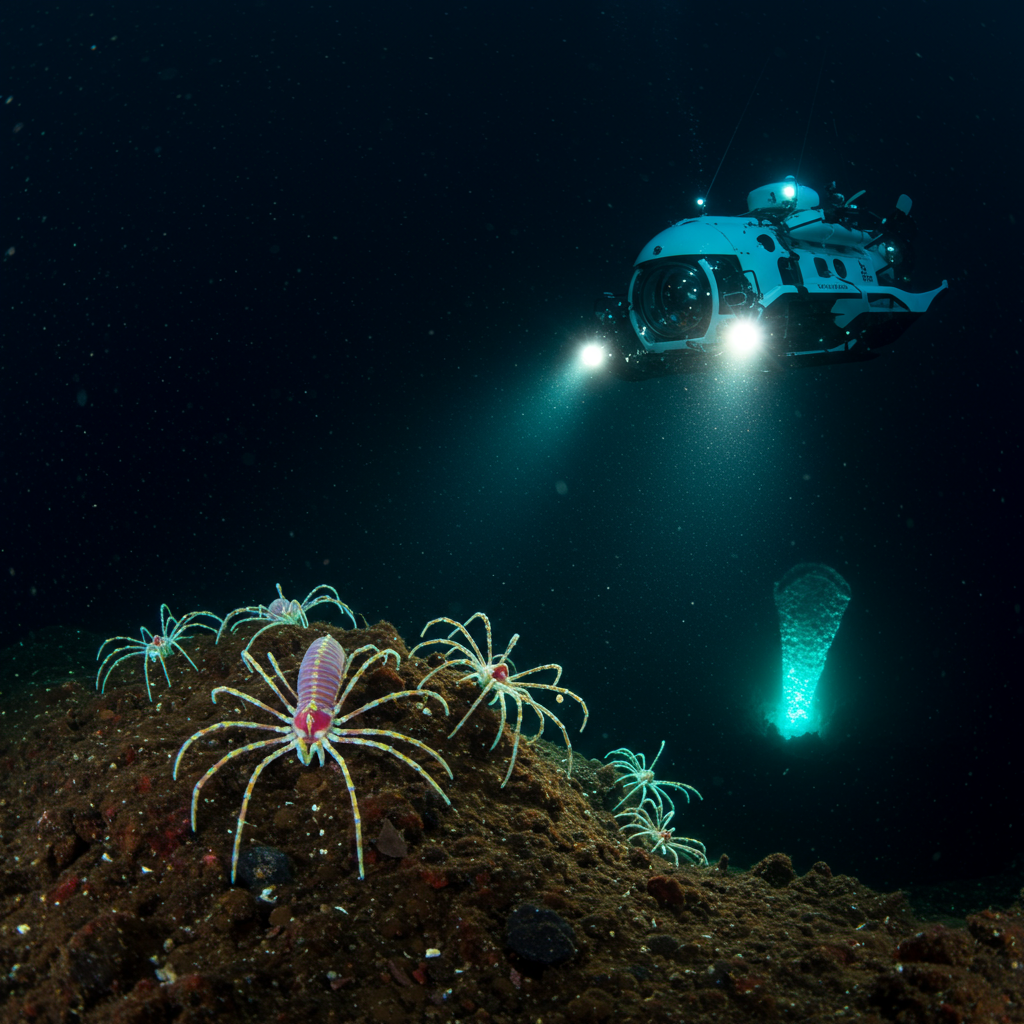

These newly identified creatures, belonging to the Sericosura genus, were found off the US West Coast. They inhabit unique, sparsely studied marine environments thousands of feet below the surface called methane seeps. These are spots on the ocean floor where natural gas bubbles up from the sediment.

A Symbiotic Feast: Spiders and Methane-Eating Bacteria

The secret to the spiders’ survival lies in an extraordinary partnership with bacteria. Instead of hunting, these sea spiders host microbes directly on their exoskeletons. In return for a place to live, these bacteria perform a remarkable feat: they convert carbon-rich methane gas and oxygen into nourishing sugars and fats.

Dr. Shana Goffredi, a biology professor at Occidental College and the lead investigator of the study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, described this feeding method vividly: “Just like you would eat eggs for breakfast, the sea spider grazes the surface of its body, and it munches all those bacteria for nutrition.”

This unique nutritional strategy is unprecedented among known sea spider species. Unlike their shallow-water cousins that often use specialized fangs to capture and consume soft-bodied prey like jellyfish, laboratory observations revealed these deep-sea Sericosura species lack the necessary tools for hunting. They are, in essence, farming their own food source.

Methane Seeps: Hotbeds of Deep-Sea Discovery

The discovery of these methane-munching spiders adds to the growing list of unique life forms found in the extreme conditions of deep-sea methane seeps. These areas, devoid of sunlight, rely on chemical energy (chemosynthesis) to support life, rather than photosynthesis.

For instance, researchers exploring methane seeps off the coast of Costa Rica recently identified another entirely new species: a vibrant, rosy-colored deep-sea worm named Pectinereis strickrotti. Found at a depth of 3,280 feet, this ragworm, resembling a centipede-earthworm hybrid with feather-like gills, highlights the incredible biodiversity hidden within these unique habitats. While its diet is still unknown, its presence underscores that methane seeps are not just feeding grounds for bacteria, but support complex ecosystems with previously unimagined creatures. Scientists continue to find more new species than they have time to name and describe, emphasizing the vast, undiscovered life in the deep ocean.

An Ecological Role and Passing the Baton

Beyond their unusual diet, these deep-sea spiders and their microbial partners may play a crucial role in preventing methane – a potent greenhouse gas – from reaching higher in the water column and potentially the atmosphere. By consuming the gas near its source, the bacteria, and subsequently the spiders, help process methane.

Dr. Goffredi notes that while the deep sea feels remote, all ecosystems are interconnected. These small animals can have significant impacts on their environment. Understanding these intricate relationships is vital for responsible stewardship of the oceans.

The potential benefits of this methane diet extend to the next generation. The translucent Sericosura spiders, measuring only about 0.4 inches (1 centimeter), are thought to have localized populations. When they reproduce (a unique process where females expel eggs from their ‘kneecaps’ and males collect them), the bacteria living on the father spiders transfer to the hatchlings. This provides the young spiders with an essential, ready-made food source from birth.

Scientists believe studying how these microbiomes are inherited in deep-sea creatures could offer insights into how microbes are passed between generations in other animals, including humans.

As exploration of the seafloor continues, more unique species like these methane-powered spiders are likely waiting to be discovered. Researchers stress the importance of understanding the high, often localized biodiversity of deep-sea habitats before potential human activities like mining risk causing irreparable harm to these unique and fragile environments.