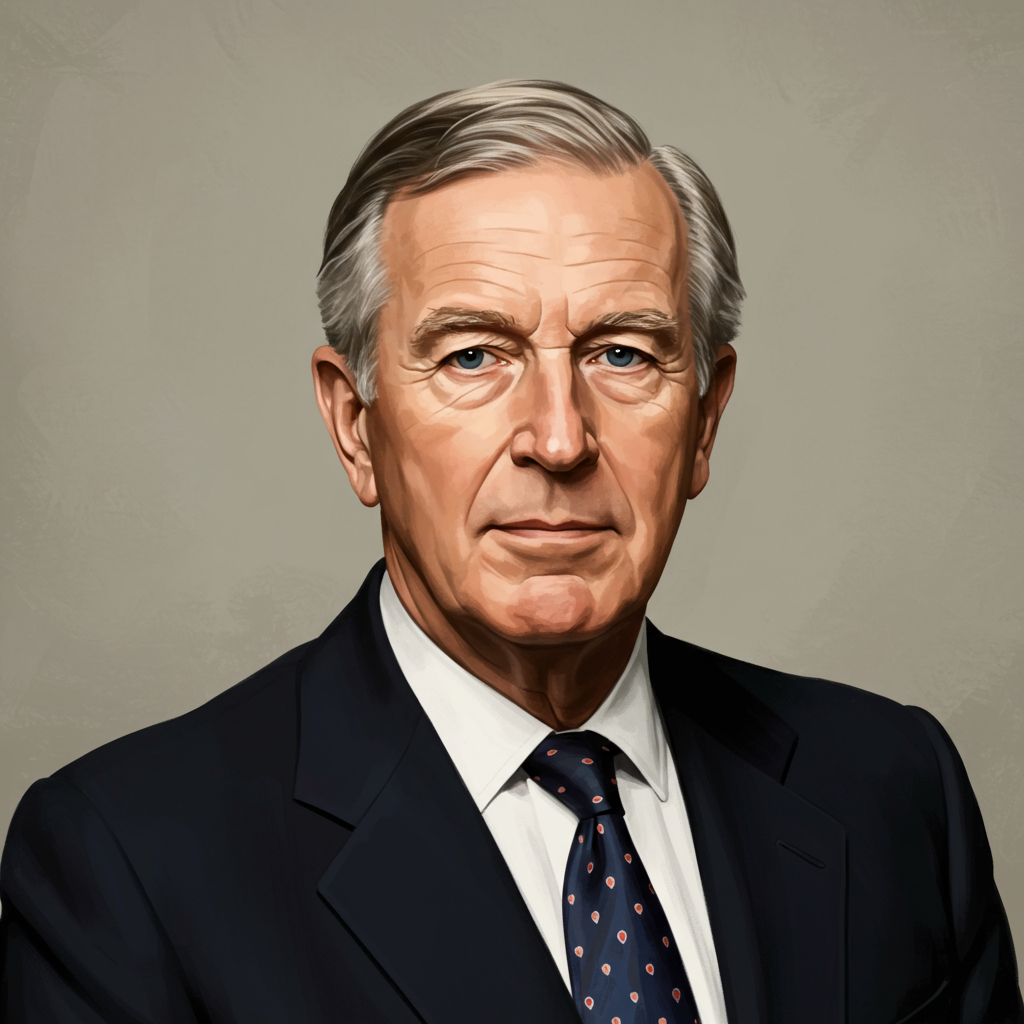

A titan of the conservative right, Norman tebbit has died at the age of 94. He stood squarely at the centre of margaret Thatcher’s transformative political era. Lord Tebbit championed a philosophy rooted in self-reliance, shaping his deeply held political convictions.

An effective and dedicated politician, his directness on subjects like immigration and Europe earned him loyalty from many Conservatives. Some even considered him a potential party leader. While his firm stances often sparked fury among opponents, he remained unfazed by criticism.

Shaping Thatcherism: From Working Class Roots

Born on March 29, 1931, in Ponders End, north London, Norman Beresford Tebbit came from a working-class background. His father managed a jewellery and pawnbroker’s business. The family had managed to buy their own house.

However, this stability proved temporary. The economic depression cost his father his job. The family then moved through various short-term rentals in Edmonton. Tebbit’s father eventually found work as a painter. His search for employment, often conducted by bicycle, became a famous anecdote.

Early Beliefs and Union Clashes

Young Norman developed an interest in Conservative politics early. Attending Edmonton County Grammar School, he embraced the idea of personal responsibility. “I felt you should be able to make your own fortune,” he later stated. “You should be master of your own fate.”

Leaving school at sixteen, he joined the Financial Times as a trainee journalist. He was annoyed by the closed shop system. It forced him to join the print union, Natsopa. After two years, he began National Service with the RAF. He gained a commission as a Pilot Officer.

However, his political hopes seemed incompatible with a service career. He left the RAF to sell advertising. He maintained his passion for flying, joining the Royal Auxiliary Air Force part-time. He narrowly survived a near-fatal crash when his jet failed to take off. Trapped in the burning wreckage, he forced open the cockpit. The aircraft was completely destroyed. Doctors later suggested a lifelong cardiac arrhythmia might have caused him to lose consciousness.

In 1953, he became a pilot for British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC). Three years later, he married Margaret Daines, a nurse. For seventeen years, he combined flying with activism for the British Airline Pilots’ Association. Ironically, the man who would later challenge Britain’s unions effectively became a major irritant to airline management during this time.

Entry into Parliament and Rising Influence

The Labour government elected in 1964 pushed Tebbit towards formal politics. He secured selection as the Conservative candidate for Epping. Winston Churchill had once held this seat. Tebbit won the nomination after a characteristically forceful speech.

His platform advocated selling state-owned industries, reforming trade unions, controlling immigration, and challenging the “permissive society.” Epping included the Labour stronghold of Harlow. An energetic campaign and the incumbent Labour MP’s overconfidence secured Tebbit’s victory in 1970.

Disillusionment and Resignation

Tebbit soon grew critical of Prime Minister Ted Heath’s leadership style. He felt Heath was ignoring the radical policies on which the Conservatives had won the election. Tebbit saw a shift towards a more consensus-driven approach. Despite his reservations, he accepted a role in 1972. He became parliamentary private secretary to the minister of state for employment. This marked his first step towards ministerial office.

However, the position did not last long. Tebbit was angered by Heath adopting a prices and incomes policy. He saw this as a clear breach of manifesto promises. He also felt Heath failed to curb union power effectively. Tebbit resigned from the government, cementing his reputation as a principled figure prepared to challenge the party line.

Three months later, the Conservatives lost power. Tebbit, now representing the new seat of Chingford, became a notable critic of Labour ministers from the backbenches. In 1975, he clashed with Employment Secretary Michael Foot. This dispute concerned the dismissal of power station workers who refused to join a union under a closed shop agreement. Tebbit enjoyed provoking ministers from the backbenches. “I was quite amused,” he said, “to find that, as a maverick backbencher… I could lure ministers into wasting their time… on such an unimportant target.” Foot famously called Tebbit a “semi-house-trained polecat” during one debate.

At the Heart of the Thatcher Revolution

When the Conservatives won the 1979 election, Margaret Thatcher brought Tebbit into government. He first served as an under secretary at the Department of Trade. Within eighteen months, he became Employment Secretary. This appointment signalled the government’s firm approach to industrial relations.

In autumn 1981, facing three million unemployed and riots in inner cities, Tebbit delivered his most memorable speech. Addressing the Conservative Party conference in Blackpool, he departed from his script. He recalled his own father’s response to job loss. “I grew up in the ’30s with an unemployed father,” he stated. “He didn’t riot. He got on his bike and looked for work, and he kept looking till he found it.”

Unions and the labour movement were outraged. They claimed Tebbit told the unemployed to “get on your bike.” Tebbit insisted his focus was on condemning the riots, not blaming the jobless. This phrase became forever linked with his name.

Key Policy Achievements

As Employment Secretary, Tebbit introduced significant reforms. His 1982 Employment Act raised compensation for workers sacked for refusing union membership. It mandated regular ballots for closed shop agreements. The Act also removed unions’ immunity from civil action for authorising illegal industrial action. Tebbit considered this act his “finest achievement in government.” These measures were instrumental in curbing the power of trade unions, a central goal of Thatcher’s government.

In 1983, he became Trade and Industry Secretary. He took over after Cecil Parkinson resigned. During his tenure, he oversaw significant parts of the privatisation programme. He also actively encouraged foreign investment in Britain. A notable success was securing the Nissan car plant establishment.

The Brighton Bombing and Its Aftermath

Life for Norman Tebbit changed dramatically in October 1984. An IRA bomb exploded at the Grand Hotel in Brighton during the Conservative conference. The attack killed five people and injured over thirty others. Tebbit and his wife, Margaret, were trapped beneath heavy debris.

They lay together, holding hands, waiting for rescue. Tebbit gave Margaret a message for their children in case he died. He suffered a broken shoulder blade, fractured vertebrae, and a cracked collar bone. He required plastic surgery but returned to work within three months.

Margaret’s injuries were far more severe. She was left paralysed and needed months of hospital treatment. She returned home using a wheelchair. Their lives changed profoundly as they adapted to her long-term care needs.

Post-Cabinet Life and Continued Influence

After a cabinet reshuffle in autumn 1985, Tebbit left the Department of Trade and Industry. He became Conservative Party chairman. He focused on revitalising the party organisation. He launched a membership drive and prepared for the next election. At the 1986 conference, he launched an election campaign disguised as a party initiative. The slogan was “The Next Move Forward.”

Margaret Thatcher’s popularity faced challenges. Some commentators discussed who might succeed her. Polls suggested Norman Tebbit could be a strong contender in a leadership contest. This reportedly created tensions with the Prime Minister. However, the 1987 election resulted in a major Conservative victory. Tebbit left the cabinet after the election to care for his wife, demonstrating his deep commitment to her.

Lord Tebbit’s Enduring Voice

Leaving cabinet did not silence Tebbit’s controversial voice. In 1990, he sparked debate with his “cricket test” suggestion. He proposed testing ethnic minorities’ assimilation by asking which country’s cricket team they supported. He declined Thatcher’s offer to return as education secretary. Yet, he steadfastly supported her during the leadership challenge that led to her resignation.

He did not seek re-election in 1992. He was created a life peer, becoming Baron Tebbit of Chingford. He remained active in the House of Lords, offering sharp commentary. He challenged Prime Minister John Major at the 1992 party conference. He strongly criticised the decision to sign the Maastricht Treaty on European integration. He later argued that the Conservative Party’s shift to the centre allowed UKIP to gain ground on the right.

A vocal eurosceptic, he campaigned for Brexit. He later expressed impatience with Theresa May’s negotiations. He accused her government of prioritizing “the rights of foreigners.” In 2009, he published ‘The Game Cook’. The book provided recipes for cooking game meat. His local butcher had told him customers didn’t know how to prepare pheasants.

In 2020, his wife Margaret passed away after suffering from Lewy Body Dementia. He had devoted many years to her care. He made his final appearance in the House of Lords two years later. This concluded a fifty-two-year parliamentary career.

Legacy and Political Philosophy

Lord Tebbit’s working-class background and dry Conservative views made him influential during and beyond the Thatcher years. He was known for his advocacy of a small state and controlled immigration. He also favoured Britain’s departure from the European Union.

He played a key role in shifting the Conservative party’s direction. Under Edward Heath, the party had favoured “one-nation centrism.” Tebbit helped move it towards a harder right stance. The satirical show ‘Spitting Image’ famously depicted him as a leather-clad “bovver boy.” This portrayed him as an enforcer of Thatcher’s policies.

One academic noted that while “Thatcherism was the political creed of Essex Man,” Norman Tebbit arguably served as its public voice. He articulated the views often associated with this demographic. He held strong views on social issues. He believed homosexuals should not hold senior cabinet posts. He thought foreign aid fueled corruption. He also felt too many immigrants failed to integrate.

Norman Tebbit’s impact on late 20th-century British politics remains significant. His unwavering belief in individual responsibility and his willingness to confront opposition defined his public life.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was Norman Tebbit most known for in politics?

Norman Tebbit is primarily known for his central role in Margaret Thatcher’s government during the 1980s. He served as Employment Secretary and Trade and Industry Secretary. He was instrumental in introducing legislation to curb the power of trade unions and overseeing early privatisation efforts. His advocacy for self-reliance and his outspoken, uncompromising style defined his political image. He was also famously linked to the phrase “get on your bike,” referencing his father’s search for work during the Depression.

What was the context of Norman Tebbit’s “get on your bike” comment?

Norman Tebbit made the “get on your bike” comment at the 1981 Conservative Party conference. This period saw high unemployment and social unrest, including riots in inner cities. While speaking about his father’s experience of unemployment in the 1930s, he said his father didn’t riot but “got on his bike and looked for work.” This statement was widely interpreted as a rebuke to the unemployed, suggesting they should take more personal initiative rather than engaging in unrest or relying on state support.

How did the Brighton bombing affect Norman Tebbit and his wife?

The 1984 IRA bomb attack on the Brighton Grand Hotel had a devastating impact on Norman Tebbit and his wife, Margaret. While Norman Tebbit suffered significant injuries (broken bones, plastic surgery) but returned to work relatively quickly, his wife Margaret was left permanently paralysed. This event profoundly altered their lives. Norman Tebbit later left cabinet in 1987 to dedicate more time to caring for her, demonstrating the deep personal consequences of the attack on his family.