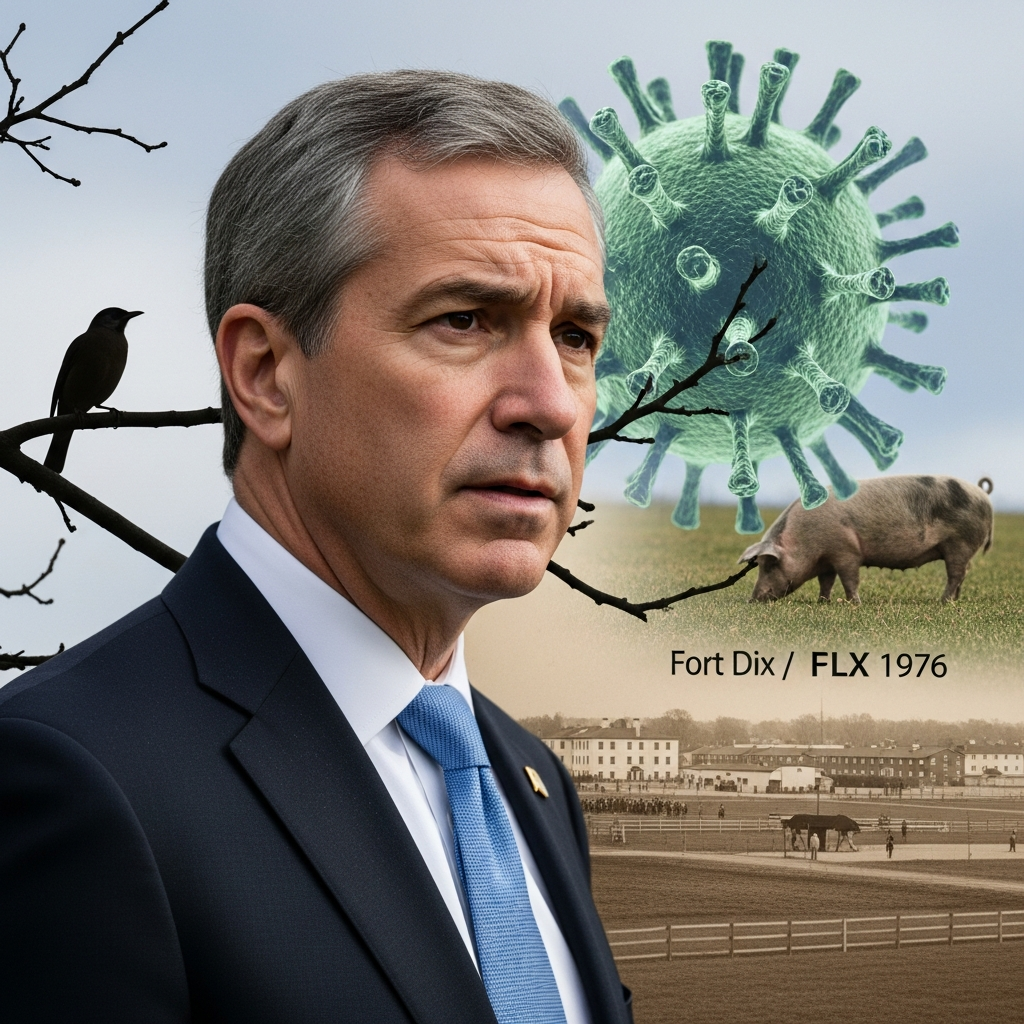

New Jersey residents often worry about public health threats, and influenza outbreaks, especially those originating from animals, are a serious concern. While “bird flu” (avian influenza) frequently makes headlines, the Garden State also has a significant history with other zoonotic flu types. Understanding past incidents, like the 1976 swine flu outbreak at Fort Dix, is vital for preparing against future viral challenges. This article explores the science of animal-borne influenza and what these events mean for public health in New Jersey.

Understanding Influenza: A Threat to New Jersey

Influenza viruses constantly evolve, posing an ongoing risk to both animal and human populations. When these viruses cross species barriers, they can create new challenges, sometimes leading to severe outbreaks. New Jersey, with its dense population and diverse ecosystems, remains vigilant against various flu strains.

What is Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)?

Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, is an infectious disease primarily found in wild aquatic birds. These viruses can also infect domestic poultry and, on rare occasions, spread to humans. While specific major human bird flu deaths in New Jersey haven’t been widely publicized, the ongoing presence of avian flu in wild bird populations across the state means it remains a constant public health consideration. Monitoring these viruses is crucial to prevent widespread outbreaks.

The Shadow of Swine Flu: New Jersey’s 1976 Outbreak

Before widespread concern about bird flu, New Jersey experienced a different kind of animal-origin influenza scare. In 1976, an outbreak of swine flu (influenza A H1N1) occurred at Fort Dix, an army base in New Jersey. This event highlighted the potential for animal-borne viruses to jump to humans and cause significant illness, even leading to a fatality. It served as a stark reminder of the unpredictable nature of influenza viruses and the need for rapid public health responses.

Deconstructing Swine Flu: From Pigs to People

Swine flu, also called hog flu or pig flu, is a respiratory illness prevalent in pigs. It is caused by influenza viruses that have historically circulated within pig populations worldwide. The characteristics of these viruses provide valuable insight into zoonotic disease transmission.

The Science Behind Swine Flu Viruses (H1N1, H3N2)

The first swine influenza virus identified was influenza A H1N1 in 1930. The “H” (hemagglutinin) and “N” (neuraminidase) refer to proteins on the virus’s surface, crucial for infection and immune response. Since 1930, other subtypes like H1N2, H3N1, and H3N2 have emerged in pigs. Notably, H3N2’s appearance in pig populations in the late 1990s is believed to have originated from humans, illustrating the two-way street of cross-species transmission. Although swine influenza viruses share similarities with human flu, their unique antigens trigger distinct immune responses.

Swine Flu in Animals: Symptoms and Spread

Swine influenza is widespread among pigs globally. Research indicates that 25 to 30 percent of pigs carry antibodies to these viruses. In the United States, the disease is endemic, with over half of pigs in some regions showing evidence of exposure. Infected pigs typically develop a flu-like illness, often seen during fall and early winter. Symptoms in pigs include a characteristic “barking” cough, fever, and nasal discharge. The illness usually resolves within about a week. The virus spreads rapidly among pigs and can readily transmit to other animal species, including birds, and importantly, to humans.

Human Impact: The 1976 Fort Dix Incident and Beyond

The potential for swine flu to infect humans has been a long-standing public health concern. While often mild, historical events demonstrate its capacity for severe outcomes.

How Swine Flu Spreads to Humans

Transmission of swine influenza to humans primarily occurs through close contact with infected pigs. This can involve direct interaction with the animals, exposure to contaminated environments like bedding or feed, or inhaling infectious airborne particles. Understanding these pathways is crucial for preventing zoonotic spread in agricultural communities and beyond.

Symptoms of Swine Flu in Humans

When humans contract swine influenza virus, they typically experience fever and mild respiratory symptoms. These may include coughing, a runny nose, and nasal congestion. Some individuals might also report gastrointestinal issues such as diarrhea and vomiting, along with chills. Importantly, human swine influenza infection rarely results in death. However, this general trend was tragically contradicted by a significant historical event in New Jersey.

Learning from History: The Fort Dix Case Study

The most well-documented instance of human swine flu involvement, including a fatality, occurred at Fort Dix army base in New Jersey in 1976. A small group of recruits at the base developed a severe respiratory illness. Tragically, one recruit died from the infection. This incident caused widespread alarm, prompting concerns about a potential pandemic. Although the virus was identified as swine influenza, its precise origin within that specific outbreak remained uncertain. The Fort Dix outbreak highlighted the need for robust disease surveillance and rapid response capabilities, serving as a critical lesson in New Jersey’s public health history.

Protecting Against Influenza: Prevention and Control

Effective management and prevention strategies are crucial for controlling animal-borne influenza, safeguarding both animal health and human populations in New Jersey.

Managing Swine Flu in Pig Populations

Currently, there are no specific antiviral drugs for treating swine flu in pigs. Therefore, supportive care is the primary approach. Essential control measures involve providing pigs with a clean and dry living environment and promptly isolating infected animals from healthy ones. Veterinarians often administer antibiotics to prevent secondary bacterial infections, which can complicate the disease and worsen outcomes. Prevention strategies for pigs primarily rely on vaccination against the circulating viral strains. Furthermore, rigorous sanitary practices are vital for containing the virus’s spread within pig populations. These include disinfecting areas previously occupied by infected pigs, properly disposing of contaminated bedding, and meticulous hand washing after handling any animals.

Public Health Measures for Zoonotic Flu Threats

For New Jersey, ongoing vigilance against both avian and swine flu is paramount. Public health authorities, working with agricultural agencies, must maintain robust surveillance systems to detect novel flu strains early. This includes monitoring animal populations for signs of disease and tracking human cases of unusual respiratory illness. For the general public, basic flu prevention strategies remain essential. Annual human flu vaccination, even if not specifically targeting zoonotic strains, can reduce the overall burden of influenza and make it easier to identify unusual outbreaks. Practicing good hygiene, like frequent hand washing and covering coughs, also helps limit viral spread. New Jersey’s public health infrastructure is continually evolving to meet these challenges, learning from past events like the Fort Dix swine flu scare.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between bird flu and swine flu, particularly regarding their impact on humans in New Jersey?

Bird flu (avian influenza) and swine flu (swine influenza) are both animal-borne viruses, but they originate in different species—birds and pigs, respectively. Both can, on occasion, infect humans. The 1976 Fort Dix incident in New Jersey involved swine flu, causing a human fatality, making it a key historical event for the state. While bird flu is a recurring concern in wild birds and poultry in New Jersey, with potential for human transmission, specific fatal human cases in the state linked to bird flu haven’t been as historically prominent as the Fort Dix swine flu event. Both require careful public health monitoring due to their zoonotic potential.

Where can New Jersey residents find current information or guidance on flu outbreaks affecting humans or animals?

New Jersey residents should consult official state health and agricultural department websites for the most current information and guidance. The New Jersey Department of Health (NJDOH) provides updates on human health risks, including seasonal influenza and emerging zoonotic threats. For animal health advisories, the New Jersey Department of Agriculture (NJDA) offers resources related to avian influenza in poultry or other animal disease outbreaks. Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website offers national and international updates relevant to public health.

How can individuals protect themselves from animal-borne influenza viruses like those seen in New Jersey?

Protecting yourself from animal-borne influenza involves several key practices. If you work with animals or visit farms, maintain strict hygiene, including thorough hand washing. Avoid contact with sick animals and follow biosecurity measures. For general flu prevention, receive your annual human influenza vaccination, which helps protect against seasonal strains and reduces the overall flu burden. Practice good respiratory etiquette, like covering coughs and sneezes, and avoid touching your face. Staying informed through official public health advisories from New Jersey authorities is also crucial for understanding local risks.

The history of influenza in New Jersey, particularly the lessons from the 1976 Fort Dix swine flu outbreak, underscores the critical importance of public health preparedness. While avian influenza remains a concern, understanding the broader spectrum of zoonotic flu threats is essential. Continued surveillance, scientific research, and proactive public health measures are vital to protect New Jersey residents from future viral challenges. Staying informed and practicing preventative health strategies are our best defenses in this ongoing fight.