Long before the internet became a global phenomenon, the iconic psychedelic rock band The Grateful Dead and their dedicated fanbase were instrumental in forging some of the earliest and most influential online communities.

The Grateful Dead were far more than just musicians; they cultivated a distinctive lifestyle and culture. Emerging from the San Francisco scene, they became synonymous with the 1960s counterculture, blending diverse musical styles with a spirit of experimentation – including an early fascination with technology.

But their influence extended beyond music and culture. Thanks to a confluence of passionate fans and technological pioneers, the Dead helped popularize what many consider the first true online community. The concepts and structures developed in this groundbreaking digital space continue to resonate in today’s interconnected world.

Deadheads: The Tech-Savvy Fandom

Fans of the Grateful Dead, affectionately known as “Deadheads,” were captivated by the band’s embrace of innovation, from cutting-edge sound systems to immersive visual experiences. Many Deadheads were themselves technologists, engineers, or academics with access to the nascent internet technology emerging in the late 1970s. They quickly adopted these tools, initially using early networks like Arpanet (a government/university precursor to the internet) to swap show setlists and connect with fellow fans. David Gans, a musician and longtime Deadhead, recalls discussions about the Grateful Dead being among the first non-technical groups to form on Arpanet.

This distributed but passionate group of fans, already connected through concerts and mailing lists, was perfectly poised to embrace the potential of online communication.

The Birth of The WELL

In the 1980s, years before the widespread adoption of the World Wide Web, a pivotal virtual online community known as The WELL (the Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link) emerged. Centered in the San Francisco Bay Area, The WELL didn’t just survive; it thrived and became a profoundly influential force in the development of the internet as we know it. A significant part of its longevity and success was directly attributable to the active participation of Grateful Dead fans.

The WELL grew out of the vision of writer, activist, and businessman Stewart Brand, creator of the influential Whole Earth Catalog. This print publication, launched in the 1970s, was inspired by the back-to-the-land movement and aimed to provide “access to tools” – its famous slogan – for building self-sufficient, ecologically, and spiritually resonant lives. It featured everything from solar stills and seed kits to books by visionary thinkers like Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan. The Catalog deeply impacted a generation, with Steve Jobs famously calling it “one of the bibles of my generation.”

Brand’s core philosophy, articulated in the Catalog, was about fostering “intimate, personal power” to counteract centralized authority. He envisioned a tool that empowered individuals.

Larry Brilliant, a doctor and activist who owned a computer company, proposed putting the Catalog online. While radical at the time, Brand saw the potential for Catalog readers to connect and converse directly. Brilliant provided the necessary funding and equipment, while Brand focused on cultivating the community’s culture. In 1985, The WELL officially launched.

A Revolutionary Online Space

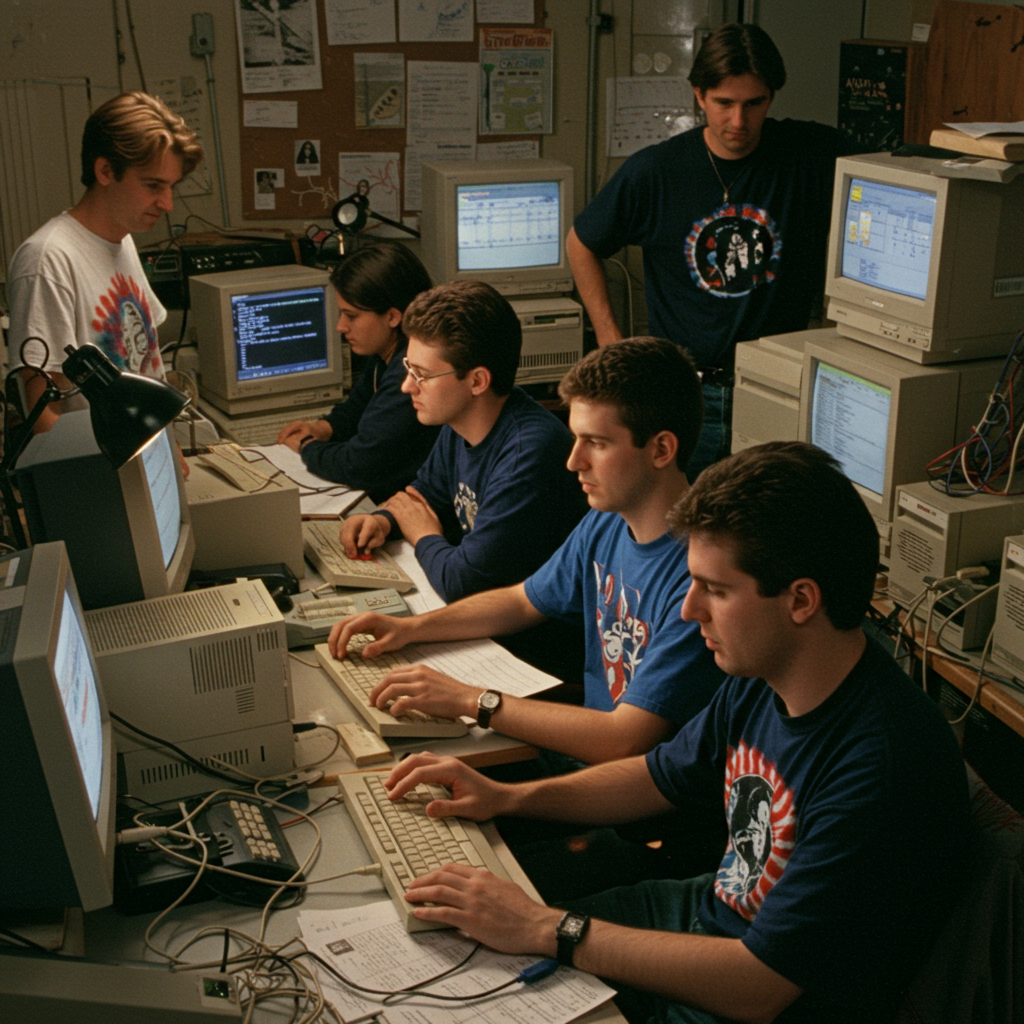

The WELL was an early bulletin board system (BBS), using text-based interfaces accessible via modem and phone line. Unlike many contemporary BBSs that were limited to single users, The WELL, running on professional PicoSpan software, boasted hardware that allowed up to fifty users to be online and chatting simultaneously. This multi-user capability was revolutionary, enabling real-time group discussions that were unprecedented for its time.

Crucially, The WELL differentiated itself from purely commercial platforms like CompuServe. Rooted in the Whole Earth Catalog‘s countercultural, do-it-yourself ethos, it was designed to foster genuine connection and discussion among diverse individuals, aiming to provoke interesting conversations and even social change.

Writer Howard Rheingold, an early adopter and devoted Whole Earth Catalog reader, quickly recognized The WELL’s potential. He joined in 1985, finding it a vital space for interaction in his solitary writing life. Rheingold coined the term “virtual community” to describe The WELL in his influential 1993 book, The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. He observed how profoundly these early networks could reshape lives.

The WELL’s initial users were a diverse mix, curated by the founders who offered free accounts to journalists, technologists, and cultural figures. The platform famously declared, “You own your own words,” establishing an early recognition of user-generated content’s inherent value – a concept central to today’s online world.

The Deadhead Phenomenon on The WELL

Among the early recipients of a free WELL account was David Gans, a musician and Deadhead who saw the platform as a perfect online home for the dispersed Grateful Dead community. Alongside Bennett Falk and Mary Eisenhart, he established the Grateful Dead forum. Eisenhart, then editor of MicroTimes, a local computer magazine, understood the fans’ need for connection, citing letters from Deadheads who felt isolated before finding community. The WELL offered a way to overcome geographical barriers and connect based on shared passion.

The Grateful Dead space on The WELL exploded in popularity. Even with a membership fee ($8 at launch) and hourly connection charges ($2/hour), Deadheads flocked to the platform. Their constant, passionate discussions about the band became a significant source of revenue, helping to sustain the entire WELL platform.

The conversations were wide-ranging. Gans noted the sheer volume of discussion eventually required splitting the single Deadhead forum into multiple dedicated spaces covering tours, tickets, and live tape trading. There was even a forum, “deadlit,” dedicated to dissecting the band’s lyrics and their literary connections, attracting figures like lyricists Robert Hunter and John Perry Barlow.

John Perry Barlow: From Lyricist to Cyber-Pioneer

John Perry Barlow himself became a prominent figure at the nexus of the Grateful Dead and early internet history. A Wyoming rancher introduced to LSD by Timothy Leary, he wrote lyrics for the Dead in the 1970s. His geographical distance from the Bay Area fueled his early interest in personal computing and online connectivity.

Barlow recognized the unique nature of the Grateful Dead fandom. As Gans recalled, Barlow described Deadheads as “a community without a physical location” years before The WELL existed.

Though initially skeptical of online avatars, Barlow quickly embraced The WELL and the emerging digital world. He became one of the first to apply William Gibson’s science fiction term “cyberspace” to the burgeoning global network. Drawing on his Western roots, Barlow saw cyberspace as an “electronic frontier,” describing early online outposts like The WELL as vast, unmapped, and culturally ambiguous – much like the Wild West.

Barlow thrived in The WELL’s eclectic environment of hackers, free speech advocates, and tech enthusiasts. He debated the future of networked communication, recognizing its transformative potential. After run-ins with law enforcement unfamiliar with digital rights, Barlow saw the urgent need to protect online users from government and institutional overreach. In 1990, he co-founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a vital advocacy group dedicated to defending civil liberties in the digital realm. Gans remarked on Barlow’s rapid transition, calling him “the Lord Mayor of cyberspace!” Decades later, the EFF remains a powerful voice in technology policy.

A Unique Incubator of Ideas

While never reaching massive user numbers (peaking around 5,000), The WELL’s impact was disproportionate to its size. It attracted many of the day’s innovators and thinkers alongside the Deadheads, including tech journalists (John Markoff, Steve Levy), entrepreneurs (Craig Newmark of Craigslist, Steve Case of AOL), computing pioneers (Steve Wozniak), hackers, phreakers, libertarians, and writers (founders of Wired magazine).

This diverse user base, though often disagreeing, fostered a uniquely vibrant and innovative environment. As Rheingold noted, “Having some friction can help foster a lot of lively conversation.” For those shaping the future of virtual communities, The WELL was the essential meeting ground. Tech executive Jim Rutt claimed that being on The WELL kept him “six months ahead of other people about what was actually happening on the internet.” It served as a crucial incubator for ideas in computing, communication, and social dynamics.

The WELL also grappled with early challenges of online governance, particularly its commitment to free speech. Moderation required extensive, sometimes thousands of posts of debate to reach consensus on handling disruptive behavior, leading to insights about the need for proactive “hosts” rather than just filters.

The WELL’s Enduring Legacy

The WELL’s ownership changed hands over the years but it remarkably still exists today, home to a small but incredibly loyal group of members, some online for nearly 40 years. Discussions are reportedly underway to archive the platform, preserving its rich history.

Looking back, Rheingold reflects on the shift away from smaller, dedicated affinity communities like The WELL. He suggests platforms like Facebook “put a damper on the proliferation of smaller communities,” favoring large audiences for data mining and advertising. As Eisenhart puts it, “Once your community members are the product rather than the customer, you don’t have a community.”

The WELL represents a unique historical moment when, in Stewart Brand’s words, “personal computer revolutionaries were the counterculture.” Long before social media saturated daily life, the concept of a dedicated, user-owned virtual community was truly pioneering – a legacy significantly shaped by the unexpected intersection of psychedelic rock and digital innovation.