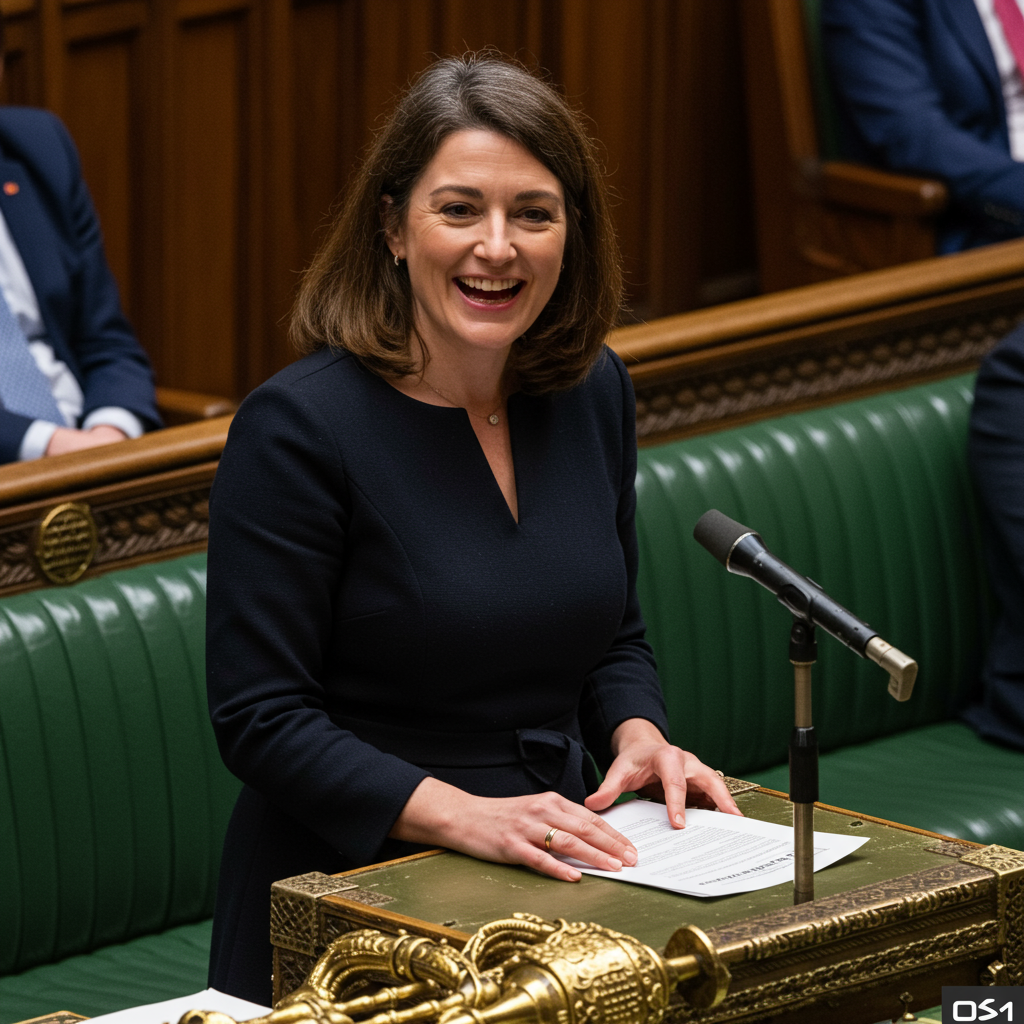

A landmark vote in the House of Commons has brought England and Wales significantly closer to legalising assisted dying for terminally ill adults. On Friday, MPs backed the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, championed by Labour MP Kim Leadbeater, in a historic decision that supporters hailed as a move towards compassion, dignity, and choice at the end of life.

However, the narrow margin of the 314-291 vote underscores the deep divisions the issue still provokes. Opponents raised serious concerns about the potential for pressuring vulnerable individuals and argued existing safeguards are insufficient.

While the principle has passed this crucial hurdle, the bill’s journey is far from over. It now moves to the House of Lords, and even if it becomes law, implementing a functional service faces complex challenges and delays.

What the Bill Proposes

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill would allow adults in England and Wales who are diagnosed with a terminal illness and have a prognosis of six months or less to live to seek an assisted death.

Under the proposed system, a patient seeking assisted dying would need approval from two doctors. Crucially, the assessment process has been strengthened during its passage through the Commons, replacing a High Court safeguard with scrutiny from an expert panel. This panel would consist of a social worker, a senior legal figure, and a psychiatrist, designed to robustly assess mental capacity and identify any signs of coercion.

If approved, a doctor would provide an approved substance, which the patient would then self-administer. Key amendments ensure that no medical or social care worker is compelled to participate in assisted dying services. Debates around whether hospices or care homes could opt out were held but not definitively settled in the bill’s current form.

The Path to Becoming Law: The House of Lords and Beyond

Having cleared the Commons, the bill now faces rigorous examination and potential amendments in the House of Lords. While Peers can propose significant changes, or even theoretically block the bill (especially as it’s a Private Member’s Bill not in the government manifesto), its passage through the Commons makes it highly likely to eventually become law. Supporters hope it could receive Royal Assent by the end of the year, potentially as early as October.

However, if the Lords propose amendments, the bill will enter a “ping pong” process, moving back and forth between the two Houses until agreement is reached. There is a risk that if this process is not completed before the current parliamentary session ends, the bill could fail and need to be reintroduced from scratch by another MP unless the government adopts it.

Intense lobbying from both sides is expected to continue as the bill progresses. Prominent opponents, including disability advocates and figures like Bishop of London Dame Sarah Mullally and disabled peer Tanni Grey-Thompson, are expected to voice strong opposition and propose amendments, particularly focusing on safeguarding vulnerable individuals and the potential strain on already stretched health and social care services.

When Could Assisted Dying Services Start?

Even with Royal Assent, assisted dying services will not become immediately available. Under the terms of the legislation approved by MPs, implementation must begin within four years of the bill passing into law, setting a deadline no later than 2029.

This extended timeframe – doubled from an initial proposal of two years – is intended to allow sufficient time to establish the complex infrastructure needed. However, it also means that many terminally ill people currently campaigning for the law change, particularly those with a short life expectancy, may sadly not live to benefit from the service themselves.

How Will an Assisted Dying Service Actually Work? Unresolved Details

Significant logistical and operational details still need to be ironed out by the government ministers tasked with implementation. These include:

Service Location: Will services be integrated within the NHS, run by separate units outside the NHS (perhaps involving third parties, similar to models in Switzerland or abortion services in the UK), or a hybrid approach?

Funding: The bill makes provision for the service to be free for patients. If publicly funded, careful consideration is needed regarding its potential impact on funding for other vital end-of-life services like hospices, which often rely heavily on charitable donations.

Medical Involvement: While doctors won’t be forced to participate, specifics around training, qualifications, and the roles of various healthcare professionals need defining.

Process Specifics: Details like the type of lethal substance, required patient identification, necessary record-keeping by doctors, and comprehensive codes of practice are yet to be decided.

A government impact assessment has provided early estimates, suggesting potential assisted deaths could range from hundreds in the first year to several thousand annually within a decade. It also estimated the annual cost of setting up and running regulatory bodies and expert panels could be over £10 million, alongside potential savings in end-of-life care costs – though savings are not the objective.

Furthermore, MPs approved an amendment requiring ministers to report within a year of the bill passing on how assisted dying could affect palliative care services, highlighting the urgent need for investment and improvement in this area regardless of the bill’s outcome. Concerns remain that without better palliative care across the board, some individuals might feel pressured towards assisted dying.

Status in Other UK Nations

This bill applies only to England and Wales. The Welsh parliament does not have a veto over this UK-wide legislation.

Other parts of the British Isles are pursuing their own paths:

Scotland: Its own Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill is progressing through the Scottish Parliament, having passed its general principles vote in May.

Isle of Man: Legislation appears closest to enactment, having passed the final vote in its parliament’s upper chamber.

Jersey: Its parliament is also expected to debate a draft law later this year.

Northern Ireland: Any similar legislation would require approval from the devolved Assembly, and there are currently no plans for its introduction.

The vote in the Commons marks a pivotal moment for assisted dying in England and Wales, but it is just one step on a long and complex road towards potential implementation.