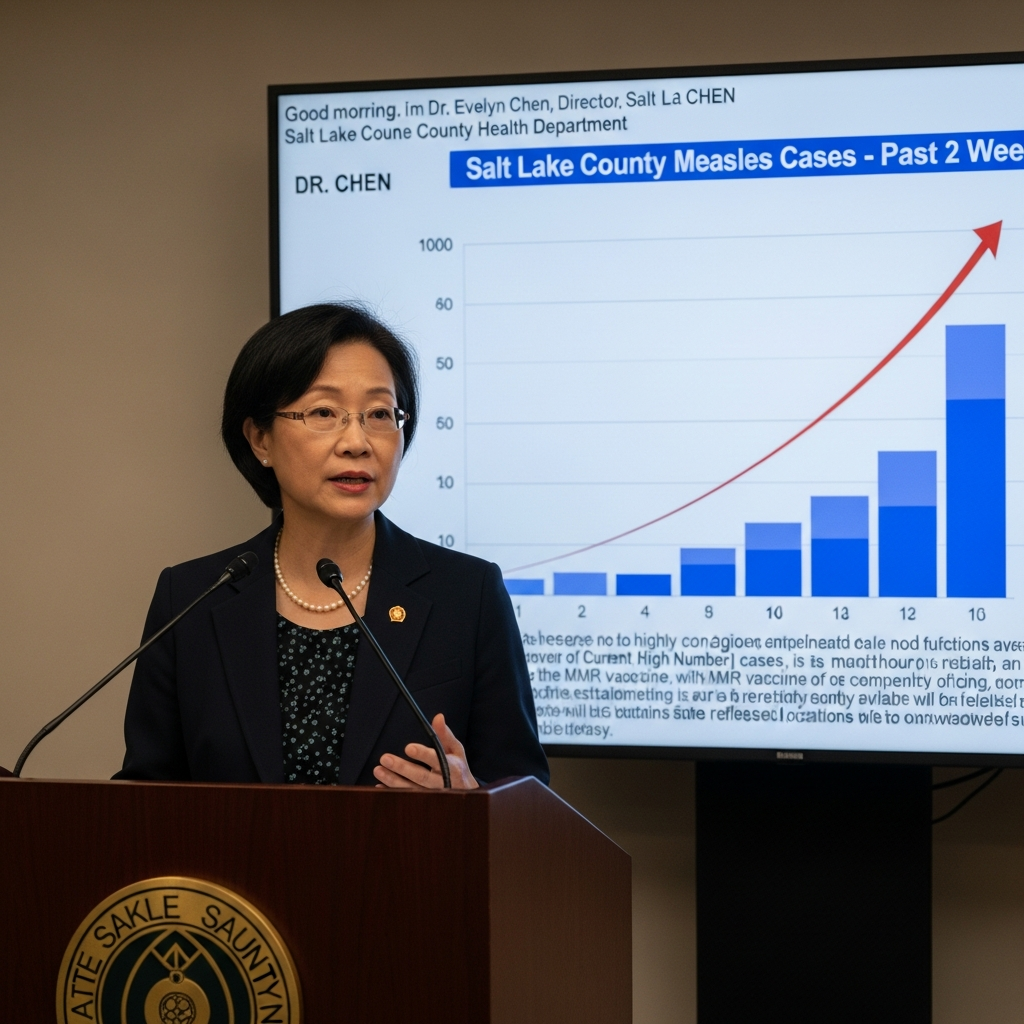

Salt Lake County is currently grappling with a significant and concerning surge in measles cases, prompting health officials to issue an urgent public health alert. With 28 confirmed cases already reported this year, a dramatic increase from just four cases in all of 2025, the highly contagious virus is actively circulating within the community. Health authorities are strongly advising residents to remain vigilant, understand the risks, and take immediate preventative measures to curb further transmission. This escalating situation underscores the critical importance of vaccination and responsible health practices to protect the public’s well-being.

Salt Lake County Confronts Alarming Measles Surge

The numbers paint a clear picture of a rapidly evolving health challenge in Salt Lake County. As of February 20, 2026, the local health department has confirmed 28 measles cases this year alone. This figure stands in stark contrast to the previous year, 2025, which saw only four cases reported across the entire county. This alarming surge highlights a renewed threat from a virus once largely under control.

Nicholas Rupp, a spokesperson for the Salt Lake County Health Department, emphasized the concerning trend. He noted that nearly all of the current confirmed cases have occurred in individuals who have not received the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. This finding points directly to vaccine status as a critical factor in the current outbreak’s spread. The first measles case in Utah for this particular outbreak cycle was reported on June 20, 2025, breaking a two-year hiatus since the state’s last positive case in March 2023.

Why Measles is a Serious Public Health Threat

Measles is renowned for its extreme contagiousness, a characteristic that makes rapid containment challenging. Health officials warn that an unvaccinated individual has a staggering 90% chance of contracting measles simply by being in the same room as an infected person, even up to two hours after the infected individual has left. This high transmissibility means the virus can spread quickly and silently.

One of the significant challenges in controlling measles is its deceptive initial symptoms. Early signs often mimic common cold or flu, including a cough, runny nose, red and watery eyes, and a fever. These symptoms can appear before the distinctive measles rash develops, making it difficult for individuals to realize they are contagious. People infected with measles are contagious for about four days before the rash appears and remain so for up to four days afterward. This extended period of contagiousness, often before a clear diagnosis, contributes significantly to community spread. Dorothy Adams, executive director of the Salt Lake County Health Department, advises anyone suspecting exposure to monitor for symptoms for a full 21 days.

Identifying Exposure Risks and Community Hotspots

The active circulation of measles has led to multiple identified exposure sites across Salt Lake County. The Utah Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) maintains an online list, which includes at least six locations within the county. These sites include high-traffic areas such as the Salt Lake City International Airport, as well as educational institutions like Intermountain Christian School and Highland High School.

A particularly concerning incident involved a student at Highland High School, part of the Salt Lake City School District. This student was on campus for several days while symptomatic before their measles case was detected, underscoring the potential for widespread exposure within schools. Additionally, multiple individuals who attended Utah’s state wrestling championships, including those at Utah Valley University and a 4A division championship at Mountain View High School, were later diagnosed with measles. These events, especially those involving student travel, highlight how the virus can rapidly move into new areas of the state, further complicating containment efforts.

Crucial Steps: Quarantine, Vaccination, and Prevention

In response to confirmed exposures, proactive measures are being implemented. For instance, district officials, in collaboration with the health department, enacted strict quarantine measures for unvaccinated students identified as exposed at Highland High. These students were explicitly prohibited from leaving their homes, attending school, working, or participating in any community or school-related activities, with their “vaccine exemption status” cited as the reason for exclusion. Vaccinated students were notified but not required to quarantine.

The most effective defense against measles remains the MMR vaccine. Health officials emphasize that two doses of the MMR vaccine prevent more than 97% of measles infections. Furthermore, vaccinated individuals who do contract measles typically experience significantly milder symptoms and are far less likely to spread the virus to others. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also recommends that adults immunized before 1968, especially if unsure about receiving a single dose, consider an updated measles shot or booster. The vaccine, while taking about two weeks for full effectiveness, can provide some protection within a few days. Parents can also discuss an early extra dose for infants aged 6 months to 1 year, or an early second dose for children who have had their first shot but not their typical second dose (usually given between ages 4 and 6), with their pediatricians.

For the community, the directive is clear: “If you have any symptoms of illness at all: stay home, don’t participate in activities.” If you suspect exposure or begin to feel unwell, it is crucial to contact a healthcare provider before arriving at a clinic or emergency room. This advance notification allows the facility to take precautions and prevent potential further transmission to other patients and staff.

The Salt Lake County Health Department’s Enduring Mission

The current measles challenge is not the first public health crisis the Salt Lake County Health Department has faced, nor will it be the last. Public health, as defined by the department’s long history, is the “science and social programs used to protect the well-being of communities.” Since its inception in 1852, the department has continuously worked to safeguard residents through medical interventions like immunizations, disease control, and establishing regulations to mitigate health risks.

This holistic approach views the community as a “patient,” requiring vigilance for “symptoms of illness” and proactive “preventative medical steps” against both existing and potential future health issues. Throughout its evolution, from the Great Sanitary Awakening to the Germ Theory era and beyond, the department has navigated complex social issues, cultural differences, and class disparities to effectively respond to disease threats. The current measles outbreak is a stark reminder of this ongoing mission and the critical role the health department plays in mobilizing resources and guiding community action to maintain public health.

Broader Implications: Utah’s Measles Outbreak Context

While Salt Lake County experiences its immediate surge, the local situation is part of a broader measles outbreak across Utah. Statewide, hundreds of cases have been reported, with Salt Lake County contributing significantly. For instance, one report indicated 32 cases in Salt Lake County as part of a larger 300-case statewide total, with 255 of those occurring in unvaccinated patients.

Amelia Salmanson, the preventable disease manager for the Utah Department of Health and Human Services, noted that Utah’s outbreak, which began in June, has progressed at a relatively steady pace compared to other states that experienced rapid surges. However, she anticipates that cases will continue to “work their way through” the unvaccinated population before a decline is observed. The hospitalization rate for measles in Utah is approximately 12% of diagnosed cases, though officials suspect that more mild cases have occurred but were neither tested nor reported, highlighting the potential for undetected spread.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the common symptoms of measles, and how soon do they appear after exposure?

Measles typically begins with symptoms resembling a common cold or flu, including a high fever (often over 103°F), cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes (conjunctivitis). A characteristic measles rash, consisting of flat red spots that appear on the face and spread downwards, usually emerges three to five days after the initial symptoms. Small white spots, called Koplik’s spots, may appear inside the mouth one to two days before the rash. Symptoms usually appear 7 to 21 days after exposure to the virus.

Where are confirmed measles exposure sites in Salt Lake County, and what should I do if I’ve been exposed?

Known measles exposure sites in Salt Lake County have included the Salt Lake City International Airport, Intermountain Christian School, and Highland High School, among others. The Utah Department of Health and Human Services maintains an updated online list of all known exposure locations statewide. If you believe you’ve been exposed, especially if you are unvaccinated, immediately contact your local health department or healthcare provider. It is crucial to call ahead before visiting any medical facility so they can take precautions to prevent further spread. Monitor for symptoms for 21 days following potential exposure.

Is the MMR vaccine still effective against the current measles strain, and who should consider getting vaccinated or boosted?

Yes, the MMR vaccine remains highly effective against the current measles strains. Two doses of the MMR vaccine provide over 97% protection against infection. Nearly all current measles cases in Salt Lake County have occurred in unvaccinated individuals, underscoring the vaccine’s importance. Unvaccinated individuals are strongly advised to get vaccinated. The CDC also recommends adults immunized before 1968, especially those unsure of their single-dose status, to consider a booster shot. Parents can discuss early vaccination options for infants (6-12 months) or an early second dose for children (4-6 years) with their pediatricians to enhance protection.

Conclusion: Vigilance is Key to Halting Measles Spread

The current surge in Salt Lake County measles cases serves as a critical reminder of the ongoing threat posed by this highly contagious virus. Health officials are clear: the best defense is prompt action, community cooperation, and widespread vaccination. By understanding the symptoms, identifying exposure risks, and adhering to public health guidelines—especially staying home when sick and ensuring vaccination—residents can collectively protect themselves and their vulnerable neighbors. This community-wide effort is essential to halt the spread, safeguard public health, and ensure Salt Lake County remains a healthy place to live.