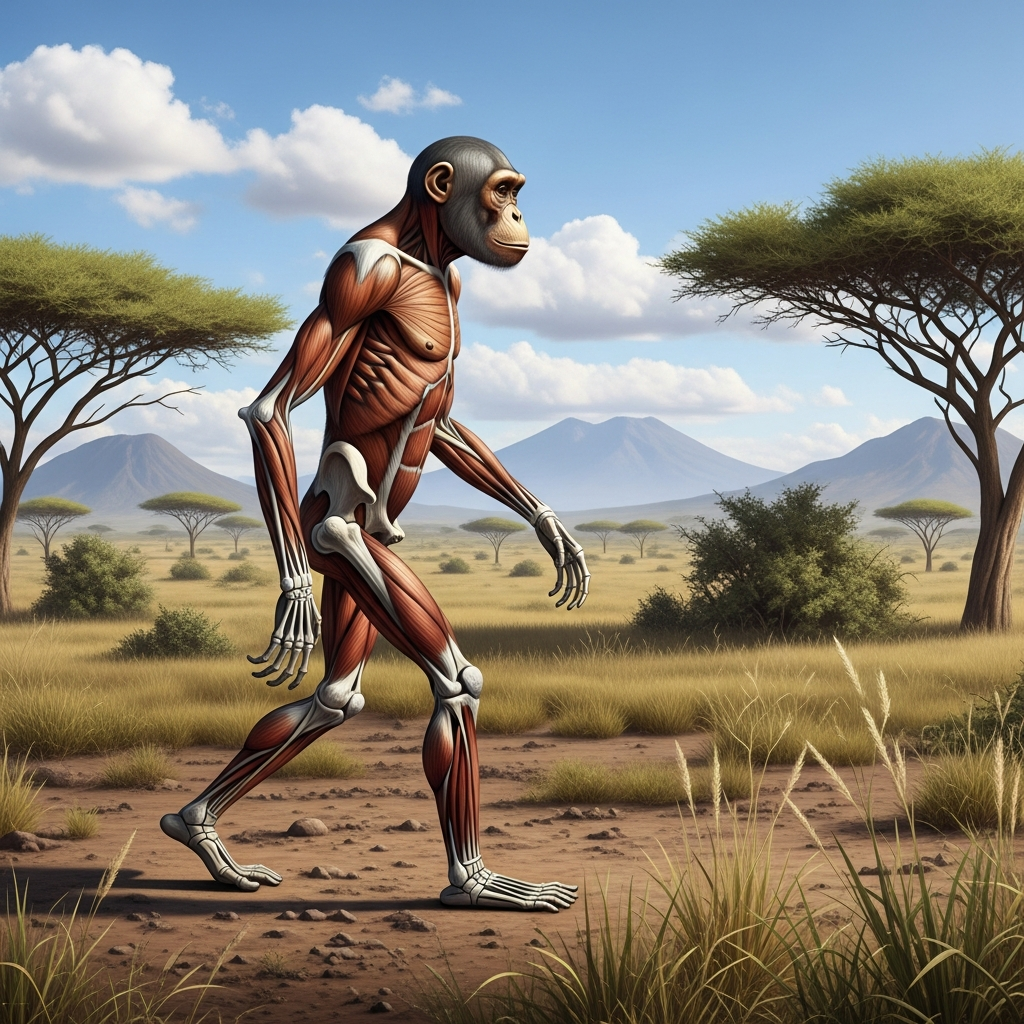

A groundbreaking new study has finally settled a longstanding debate in paleoanthropology, providing definitive anatomical evidence that Sahelanthropus tchadensis, our 7-million-year-old earliest known ancestor, walked upright on two legs. This pivotal discovery reshapes our understanding of human evolution, suggesting that bipedalism, a hallmark of the human lineage, emerged much earlier than previously thought, close to the divergence from chimpanzees. Unlocking the secrets of Sahelanthropus’ locomotion offers profound insights into the very first steps of humanity.

Unearthing Humanity’s First Steps: The Sahelanthropus Revelation

For decades, the fossil record of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, discovered in Chad during the early 2000s, has been a source of intense scientific discussion. Initial studies focused on its skull, with features at the base hinting at an upright posture. However, a skull alone offered limited conclusive evidence about how this ancient hominin truly moved. Subsequent examinations of its limb bones, including a forearm and a thigh bone, led to varied interpretations. Some researchers emphasized traits consistent with tree climbing, while others pointed towards bipedal movement.

This new research, published in Science Advances, meticulously re-examined these crucial limb bones. Scientists employed high-resolution 3D shape analysis and extensive comparisons with both living apes and other fossil hominins. This advanced approach allowed the team to precisely differentiate anatomical features indicative of bipedal walking from those related to climbing or more generalized quadrupedal movement. The goal was to provide an unambiguous answer to one of human evolution’s most fundamental questions.

Beyond the Skull: Limb Bones Tell the Tale

The key to resolving the Sahelanthropus locomotion mystery lay in these previously debated limb bones. Through sophisticated analysis, researchers could discern subtle yet critical anatomical markers. This detailed investigation went beyond superficial observation, delving into the nuances of bone structure and articulation. The comparative method, examining a broad range of primate and hominin fossils, proved instrumental. It allowed scientists to identify features that unequivocally signaled an adaptation for upright movement.

The Definitive Evidence: Key Anatomical Markers of Bipedalism

The new study pinpointed several anatomical features in Sahelanthropus tchadensis that strongly support its bipedal capability. These markers are not isolated anomalies but form a coherent picture of a species adapted for upright walking. The precision of modern imaging and comparative anatomy finally brought clarity to these ancient bones. Each piece of evidence contributed to building an undeniable case for early bipedalism.

The Crucial Femoral Tubercle

Perhaps the most compelling evidence identified was the presence of a femoral tubercle on the thigh bone. This small, yet highly significant, projection serves as the attachment point for the iliofemoral ligament. In humans, this is the strongest ligament in the body, vital for stabilizing the hip joint during upright standing and walking. Remarkably, the femoral tubercle had previously been documented only in bipedal hominins. Its discovery on the Sahelanthropus femur provides a direct anatomical link to later bipedal species. This single feature offers powerful proof of its walking style.

Complementary Bipedal Traits

In addition to the femoral tubercle, the analysis confirmed two other critical traits associated with bipedal locomotion. First, a natural twist in the femur helps orient the legs forward, a characteristic seen in upright walkers. Second, the pattern of gluteal muscle attachment found in Sahelanthropus was comparable to that seen in early human ancestors like Australopithecus. These features collectively enhance hip stability, which is essential for maintaining balance during bipedal movement. Furthermore, the species’ limb proportions, characterized by a relatively long thigh bone compared to its forearm, also differ from those of modern apes. This further indicates an early evolutionary shift towards bipedal movement.

Sahelanthropus: A Bipedal Ape in a Changing World

The findings paint a fascinating picture of Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Scott Williams, a study author, aptly described it as “essentially a bipedal ape.” This phrase highlights its unique transitional nature. Despite its capacity for upright walking, Sahelanthropus retained many ape-like characteristics. It possessed a chimpanzee-sized brain and likely spent a significant portion of its time in trees. Climbing would have been crucial for foraging and seeking safety from predators. This dual adaptation suggests a versatile lifestyle.

This species, from 7 million years ago in what is now Chad, represents a critical juncture. It demonstrates that bipedalism evolved early in the human lineage, even before the development of larger brains or sophisticated tool use. This challenges previous theories that suggested bipedalism appeared only after substantial shifts in body size or brain anatomy. Instead, it indicates that upright movement evolved in an ancestor that still shared many characteristics with its ape relatives. Sahelanthropus tchadensis therefore provides a vital glimpse into the behavior of our earliest bipedal forebears.

Rewriting the Story of Human Evolution

The emergence of bipedalism as early as 7 million years ago fundamentally alters our understanding of human evolution. It places upright walking at the very foundation of our lineage, long before other major evolutionary milestones. This challenges older notions that bipedalism was a consequence of environmental changes requiring long-distance travel, or directly linked to increasing brain size. Instead, it suggests a more complex, perhaps opportunistic, pathway to evolving on two feet. Sahelanthropus tchadensis is now firmly established as a crucial early bipedal hominin, whose behavioral repertoire already included upright movement.

This discovery emphasizes that evolution is not a linear progression but a mosaic process. Different traits can evolve at different rates and in different sequences. Understanding the environmental context in which Sahelanthropus lived is also crucial. While the study primarily focuses on anatomy, insights from other branches of paleoanthropology offer a broader context.

New Windows into Ancient Worlds: Beyond Anatomy

While anatomical studies like that of Sahelanthropus tchadensis provide direct evidence of physical adaptations, other scientific advancements are dramatically expanding our view of ancient life. Researchers are now employing revolutionary techniques to gain a more complete picture of prehistoric worlds. These interdisciplinary approaches add incredible depth to our understanding of ancient environments and the organisms that inhabited them.

For instance, the pioneering application of metabolomics to fossilized bones is transforming paleontology. This technique analyzes thousands of preserved metabolic molecules, or metabolites, within ancient remains. These metabolites offer an unprecedented window into the daily lives, health, diets, and environments of prehistoric animals. By studying metabolites trapped in bone’s microscopic structures, scientists can reconstruct ancient ecosystems with remarkable detail. They are able to identify specific plants consumed, infer climate conditions like temperature and rainfall, and even detect ancient diseases. This groundbreaking method, applied to animal bones from early human activity sites in East and South Africa, reveals that these ancient environments were often significantly wetter and warmer than the same regions are today. Such insights provide a rich environmental backdrop, allowing us to better imagine the world in which Sahelanthropus and other early hominins took their first steps.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the significance of Sahelanthropus tchadensis for human evolution?

Sahelanthropus tchadensis is considered one of the earliest known members of the human family tree, dating back approximately 7 million years. The new study definitively confirms its capacity for bipedalism, or upright walking. This is incredibly significant because it means that walking on two legs, a defining characteristic of humans, emerged very early in our lineage, close to when humans and chimpanzees diverged. This discovery challenges previous ideas that bipedalism evolved much later, after other changes like brain enlargement.

Where was Sahelanthropus tchadensis discovered, and when did it live?

Sahelanthropus tchadensis was discovered in the Djurab Desert of Chad, Central Africa. Its fossils are estimated to be around 7 million years old, placing it firmly at the very beginning of the known human evolutionary timeline. The remote location of its discovery, far from the traditional East African “cradle of humanity,” also broadens our understanding of the geographical scope of early hominin evolution.

How does the new evidence of bipedalism in Sahelanthropus change our understanding of early human ancestors?

The definitive evidence for bipedalism in Sahelanthropus tchadensis revolutionizes our understanding by showing that upright walking did not necessarily follow the development of larger brains or tool use. Instead, it was an early and perhaps foundational adaptation. This suggests that the evolutionary path to becoming human was complex, with different traits developing independently and at various times. It recontextualizes Sahelanthropus as a “bipedal ape” that still likely spent time in trees, highlighting a mosaic evolution where new adaptations coexisted with older ones.

The Future of Paleoanthropology

The study of Sahelanthropus tchadensis exemplifies the dynamic nature of paleoanthropology. Each new fossil find and every re-evaluation using advanced techniques holds the potential to rewrite chapters of our evolutionary story. The ongoing dedication of researchers to meticulously analyze ancient remains, combined with innovative scientific methods like metabolomics, promises even more remarkable discoveries. These insights not only inform us about our past but also highlight the incredible adaptability of life on Earth. As we continue to uncover these ancient secrets, we gain a deeper appreciation for the long and winding journey that led to modern humanity.