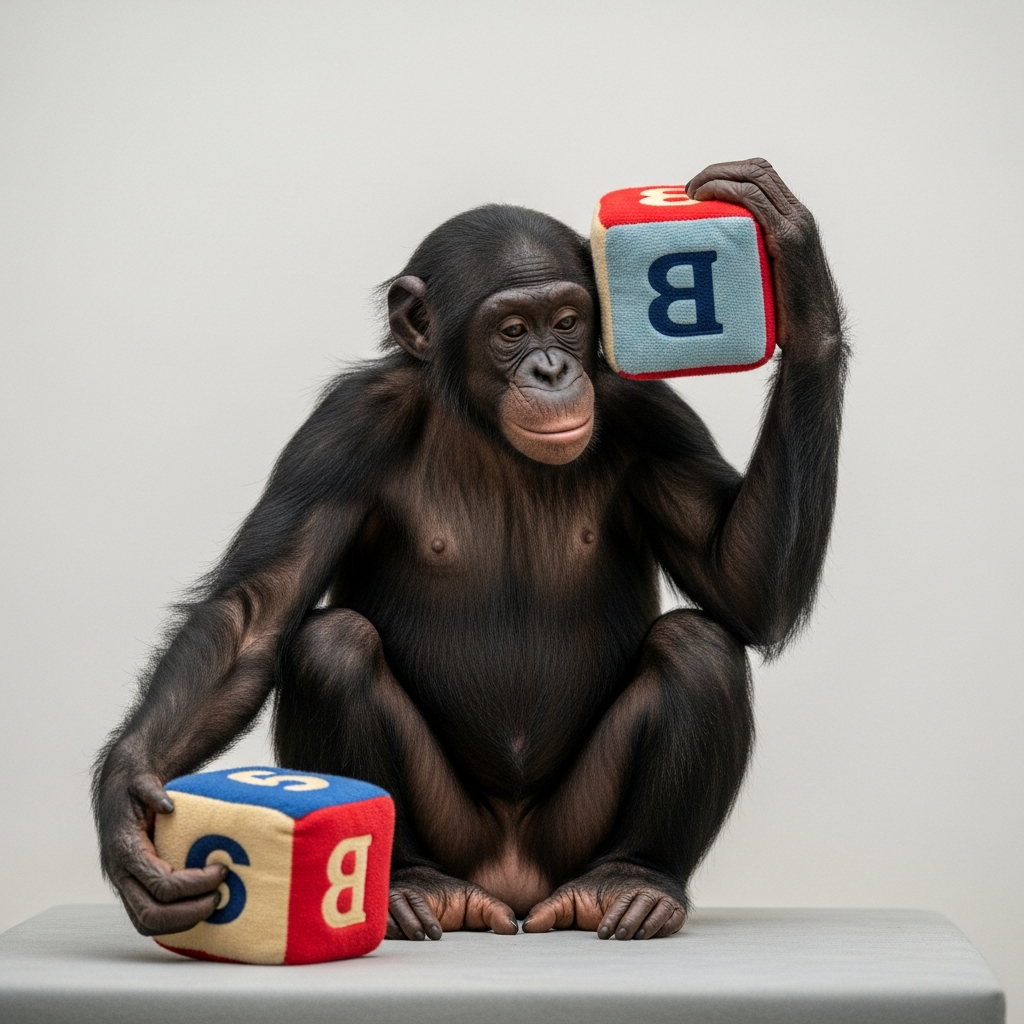

A revolutionary study has shattered long-held beliefs, providing compelling evidence that bonobos possess the remarkable ability to imagine and engage in pretend play. This groundbreaking research, published in the prestigious journal Science, challenges the notion that these sophisticated cognitive skills are exclusive to humans, offering a profound glimpse into the rich mental lives of our closest living relatives. The findings suggest that the roots of imagination run far deeper in our evolutionary history than previously thought, potentially tracing back millions of years.

The Pioneering Research with Kanzi the Bonobo

The core of this transformative study revolved around an extraordinary bonobo named Kanzi. Renowned for his unique upbringing and extensive language training, Kanzi, who sadly passed away in March 2025 at the age of 44, was an ideal subject. His ability to understand spoken English and communicate using lexigrams provided researchers with unprecedented access to the mind of a non-human primate. This allowed scientists to test his imaginative capabilities in ways typically reserved for young children.

Researchers, including Christopher Krupenye, an evolutionary cognitive scientist at Johns Hopkins University, and Amalia Bastos, a comparative psychologist at the University of St. Andrews, meticulously designed a series of “tea party-like” experiments. These ingenious tests aimed to determine if Kanzi could conceptualize and track imaginary objects, a key component of pretend play.

Unveiling “Secondary Representation” Through Clever Experiments

The study’s design focused on “secondary representation”—the cognitive capacity to simultaneously hold both a primary understanding of reality (e.g., an empty cup) and a decoupled, imaginary representation (e.g., a cup containing pretend juice). This dual awareness is crucial for true make-believe.

In the first primary experiment, dubbed the “Invisible Juice Experiment,” Kanzi was presented with two transparent, empty cups and an empty pitcher. A researcher then mimed pouring “pretend juice” from the pitcher into both cups. Following this, the researcher pretended to pour the imaginary juice out of one of the cups back into the pitcher. When Kanzi was asked, “Where’s the juice?” he consistently pointed to the cup that should still contain the imaginary liquid. This occurred in a remarkable 68% of the trials, significantly higher than mere chance. Kanzi’s immediate understanding, without a learning curve, suggested an intuitive grasp of the scenario.

To confirm Kanzi wasn’t simply reacting to the researcher’s movements or believing in invisible juice, a crucial “Distinguishing Fantasy from Reality” control trial was conducted. Kanzi was offered a choice between a cup containing real orange juice and a cup with “pretend juice.” Overwhelmingly, he chose the real juice in 77.8% of cases. This demonstrated his clear ability to differentiate between fantasy and reality, confirming his deliberate participation in the make-believe game. As co-author Amalia Bastos remarked, Kanzi could “generate an idea of this pretend object and at the same time know it’s not real.”

The findings were further generalized in a “Conceptual Replication” experiment. Here, researchers used imaginary grapes instead of juice, placing them in jars. After one jar was “emptied,” Kanzi was again successful in identifying the location of the remaining imaginary grape. This replication solidified the findings, ruling out simpler explanations like mere imitation or reaction to stimuli.

Beyond Human Exceptionalism: Evolutionary Roots of Imagination

These compelling results challenge the long-held notion of human exceptionalism in complex cognitive processes. Experts like Christine Webb, a researcher at New York University, describe the findings as “compelling evidence” for secondary representation in bonobos. The study suggests that the cognitive machinery for imagination, a skill vital for planning, problem-solving, and social understanding, may have evolved much earlier than previously thought.

The authors propose that this ability to imagine pretend scenarios and objects could date back 6 to 9 million years. This timeframe corresponds to the last common ancestor shared by humans, bonobos, and chimpanzees. This deep evolutionary root implies that our ancestors may have also possessed similar imaginative capacities. Furthermore, it opens the intriguing possibility that apes might leverage imagination for other sophisticated cognitive tasks, such as visualizing potential futures or inferring the thoughts of others – a skill bonobos like Kanzi have previously demonstrated.

The study aligns with a growing body of evidence indicating that many traits once considered uniquely human are, in fact, shared with other animals. Jan Engelmann, an associate professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, emphasizes that these experiments bolster the evidence that apes can engage in complex thought processes like planning, reasoning, and inferring cause and effect through “secondary representations.” Kristin Andrews, a professor of philosophy at CUNY Graduate Center, highlights the evolutionary advantage of such abilities, allowing individuals to mentally test actions before executing them in reality.

The Unique Case of Kanzi and Future Research Directions

While the study’s conclusions are robust, researchers acknowledge Kanzi’s unique background. His extensive interaction and training with humans made him an exceptional subject. Natalie Awad Schwob, a comparative psychologist at Bucknell University, stresses the need for data from “more typically reared bonobos and chimpanzees” to determine if this imaginative streak is unique to Kanzi or a more widespread capacity within the species. Christopher Krupenye agrees, suggesting that future experimental setups can be designed without verbal cues to accommodate less conversant bonobos.

The question remains whether Kanzi’s language training specifically primed him for these cognitive feats, or if it simply provided a means for researchers to access an inherent capacity. Regardless, Kanzi’s lifelong contributions to science, encompassing insights into primate cognition, early tool-making, and language evolution, have been invaluable. His extraordinary communicative abilities provided “direct access to the mind of a bonobo,” profoundly enriching our understanding of both ape minds and the nuances of human cognition.

A Powerful Call for Conservation

Beyond the profound scientific implications, the researchers draw a crucial connection between these discoveries and the urgent need for conservation. If great apes possess such rich inner lives, capable of imagination and complex thought, it underscores the profound tragedy of their precarious existence. Bonobos are critically endangered, found exclusively in the Democratic Republic of Congo. They face severe threats including:

Habitat Loss: Driven by industrial agriculture (palm oil and rubber) and logging.

Poaching: Fueled by the illegal bushmeat trade.

Disease Outbreaks: Vulnerability to human diseases.

Civil Unrest: Disrupting conservation efforts and increasing threats.

Their slow reproductive rate makes them particularly vulnerable, with every individual loss having a devastating impact on population recovery. The authors hope these findings will foster a greater appreciation for these intelligent creatures. A deeper understanding of bonobos’ complex mental lives should compel increased conservation efforts to protect their shrinking forest homes from human-induced destruction, ensuring their future survival.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did scientists prove bonobos can imagine?

Scientists used a series of “tea party-like” experiments with Kanzi, a language-trained bonobo. In one key trial, they mimed pouring “pretend juice” into empty cups, then “emptied” one. When asked where the juice was, Kanzi consistently pointed to the cup that should still contain the imaginary liquid. Control experiments confirmed he could differentiate between real and pretend, demonstrating his ability to track imaginary objects and engage in make-believe scenarios.

What is ‘secondary representation’ in animal cognition?

Secondary representation is the cognitive ability to hold and process two distinct mental states simultaneously: a primary representation of reality (e.g., an empty cup) and a secondary, decoupled representation (e.g., the same cup containing imaginary juice). This allows an individual to understand and engage with pretend scenarios while remaining aware of the actual physical reality. The study found this capacity in bonobos, challenging its previous attribution as a uniquely human trait.

Why is understanding bonobo imagination important for conservation?

Discovering that bonobos possess advanced cognitive abilities like imagination underscores their complex inner lives and intelligence. This profound understanding elevates their status, moving beyond simplistic views of animals. Researchers hope this insight will foster greater empathy and appreciation for bonobos, highlighting the immense value of protecting these critically endangered species and their fragile habitats in the Democratic Republic of Congo from threats like habitat loss and poaching.

Conclusion

The groundbreaking study on bonobos’ imagination represents a significant paradigm shift in our understanding of primate cognition and human evolution. Through the extraordinary insights provided by Kanzi, we are reminded that complex mental lives are not exclusive to our species. The capacity for bonobos imagination, rooted deep in our shared ancestry, urges us to rethink our place in the animal kingdom and reinforces our responsibility to protect these intelligent, endangered beings. Supporting conservation efforts for bonobos is not just about preserving a species; it’s about safeguarding a vital link to our own cognitive past and recognizing the rich, diverse intelligence that thrives on our planet.