The intricate tapestry of human evolution has just gained another fascinating thread. A groundbreaking recent study, published in the esteemed scientific journal Nature, has finally resolved a 16-year-old mystery, officially identifying a distinctive fossilized foot as belonging to Australopithecus deyiremeda. This enigmatic species, previously a subject of debate, now stands confirmed as a contemporary of the famous “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis), dramatically reshaping our understanding of our ancient family tree and the diverse paths early hominins explored in northeastern Ethiopia over 3.4 million years ago.

This pivotal discovery paints a vivid picture of a bustling Pliocene landscape, where multiple hominin species navigated their world with unique adaptations. Far from a linear progression, our ancestry appears to be a complex web of “cousins” coexisting, each thriving through different survival strategies.

Unearthing the Burtele Foot: A Puzzling Anomaly

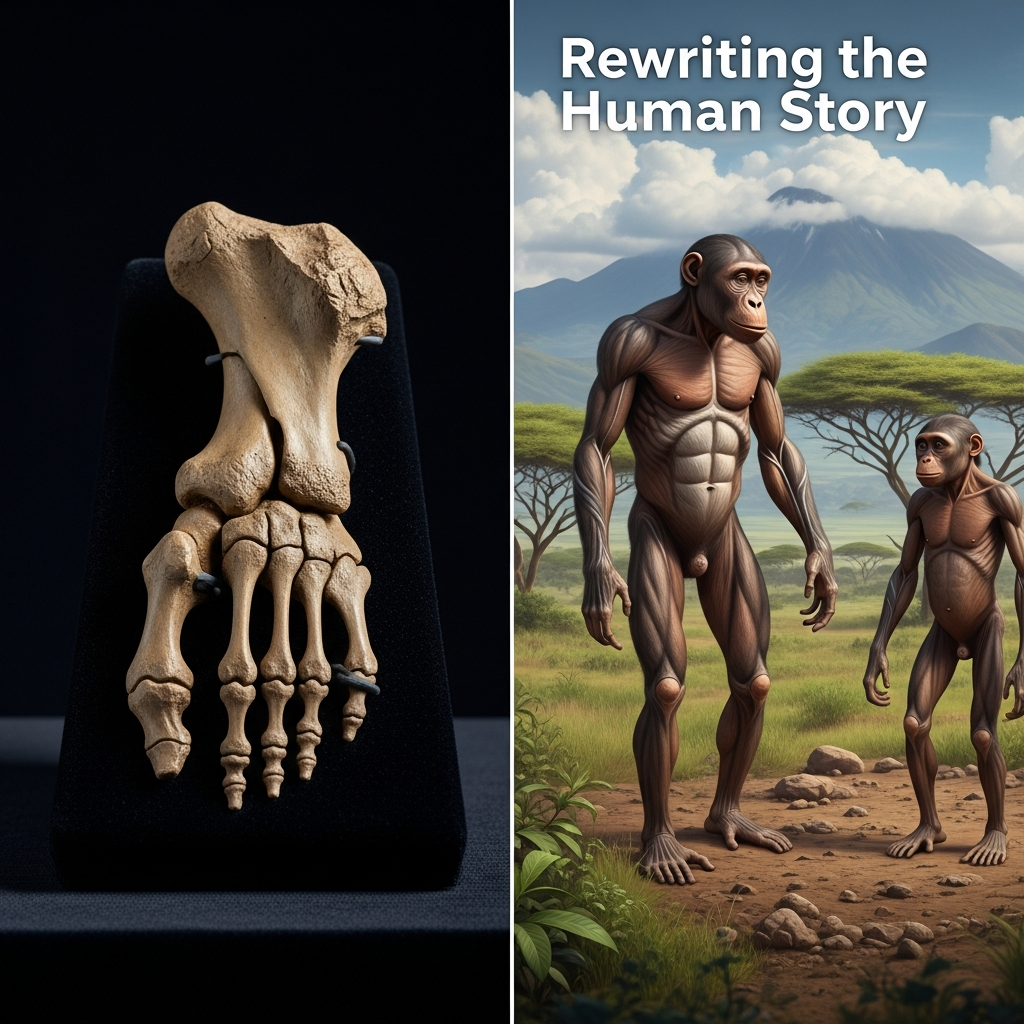

The story began in 2009 with the excavation of an unusual fossilized foot, now known as the “Burtele foot,” from the fossil-rich grounds of Burtele in Ethiopia. What immediately struck researchers was its distinctive anatomy. Unlike Lucy’s foot, which was clearly adapted for bipedalism and terrestrial locomotion with an aligned big toe, the Burtele foot featured a grasping, opposable big toe—much like a human thumb. This singular characteristic strongly suggested its owner was a skilled climber, spending a significant portion of its life navigating trees.

For years, this unique foot presented a paleoanthropological puzzle. While Lucy’s species was widely considered a foundational ancestor for later hominins, the Burtele foot hinted at a parallel lineage with a very different lifestyle. It challenged the prevailing notion that early hominins were uniformly embracing ground-dwelling bipedalism by Lucy’s time, sparking intense scientific curiosity.

Lucy’s World: A Glimpse into Early Hominin Life

Lucy, or Australopithecus afarensis, is one of the most iconic ancient human relatives. Discovered in 1974, her relatively complete skeleton provided compelling evidence for early bipedalism, signifying a major evolutionary leap. She primarily roamed open environments, her anatomy optimized for walking upright on the ground. For decades, Australopithecus afarensis was largely viewed as the sole dominant hominin species in East Africa during its time, standing as a direct ancestor to our genus, Homo. The existence of another contemporary species, especially one with such distinct features, therefore held profound implications for how we trace our origins.

Solving the Mystery: Connecting Foot to Jaw

The definitive breakthrough arrived with subsequent excavations at the nearby Woranso-Mille site, close to the original Burtele foot discovery. Led by paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie, director of Arizona State University’s Institute of Human Origins, researchers uncovered additional crucial fossils. These included a remarkably well-preserved jawbone containing 12 teeth, dating to the same period as the Burtele foot.

Analyzing the morphology of these newly found teeth and jaw fragments, the team confidently identified them as belonging to Australopithecus deyiremeda. This species had actually been named in 2015 based on earlier jaw and tooth discoveries from the same region, though its existence and connection to the enigmatic Burtele foot remained controversial. The latest evidence, particularly the close proximity and similar age of the new dental remains to the foot, provided the much-needed confirmation. John Rowan, an assistant professor of human evolution at the University of Cambridge, affirmed the study’s conclusions as “very reasonable,” noting the strengthened evidence for a distinct, coexisting species.

Distinct Adaptations: Life in Different Niches

The identification of the Burtele foot with Australopithecus deyiremeda not only confirms the species but also illuminates its unique ecological niche. The grasping big toe, long curved toes, and flexible foot bones underscore its pronounced arboreal adaptation. This early human relative likely spent a significant amount of time in forested environments, climbing trees for safety and sustenance.

Further insights came from detailed isotopic analysis of A. deyiremeda‘s teeth. These revealed a distinct diet primarily consisting of leaves, fruits, and nuts, typical of a forest-dweller. This contrasts sharply with Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, which had a broader, more omnivorous diet and favored more open, mixed woodlands and grasslands. These dietary and locomotor differences are crucial, as Ashleigh L.A. Wiseman, an assistant research professor at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, points out, indicating the two species were “unlikely to be directly competing for the same resources.” This ecological partitioning allowed them to successfully share the same Pliocene landscape.

Reshaping the Human Family Tree: A Story of Diversity

The revelation of Australopithecus deyiremeda‘s confirmed presence alongside Lucy fundamentally challenges the long-held notion of human evolution as a straightforward, linear progression. Instead, it strongly supports a more complex “family tree” model, teeming with diverse hominin species, many of whom were “cousins” coexisting rather than one species simply giving rise to the next.

This discovery highlights the period as one of significant “evolutionary experimentation,” particularly concerning bipedalism. While Lucy’s species refined its terrestrial upright walking, A. deyiremeda appears to have maintained strong arboreal capabilities while perhaps also engaging in some form of bipedal movement on the ground, representing a different “experiment” in locomotion. Carol Ward, an anthropologist at the University of Missouri, emphasizes that the coexistence of different hominin species, navigating the world in distinct ways, fundamentally reshapes our understanding.

Implications for Ancestry and Future Discoveries

The growing number of well-documented human-related species, including Australopithecus deyiremeda, deepens the mystery of our direct lineage. As Rowan contends, “Which species were our direct ancestors? Which were close relatives? That’s the tricky part.” The increased species diversity means a greater number of plausible reconstructions for how human evolution unfolded. While A. deyiremeda‘s more primitive features and specialized foot make it an unlikely direct ancestor to the genus Homo compared to Lucy, its existence reminds us of the rich biodiversity of early hominins.

The scientific community’s initial skepticism surrounding A. deyiremeda in 2015 has largely dissipated with these new, compelling fossil finds. However, Wiseman offers a cautionary note, reminding us that definitive species assignments often ideally rest on well-preserved skull fragments and evidence from multiple associated individuals. While the research significantly strengthens the case for A. deyiremeda‘s distinct existence, she acknowledges it “doesn’t remove all other alternative interpretations.” This ongoing scientific debate underscores the dynamic and evolving nature of paleoanthropology. Researchers continue their work at the Burtele and Woranso-Mille sites, hoping to unearth more clues about this fascinating species and further unravel the intricate story of our deep past.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Australopithecus deyiremeda and how does it differ from Lucy?

Australopithecus deyiremeda is a recently confirmed ancient human relative that lived in Ethiopia approximately 3.4 million years ago, concurrently with the more famous “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis). A key distinguishing feature is its foot, which possessed an opposable big toe similar to a human thumb, indicating it was a skilled climber and spent significant time in trees. In contrast, Lucy was more adapted for terrestrial bipedalism, predominantly walking on the ground. Additionally, A. deyiremeda had a specialized diet of leaves, fruits, and nuts from forested areas, while Lucy’s species consumed a broader diet from more open environments.

Where was the Burtele foot discovered, and what other evidence supports this new species?

The enigmatic “Burtele foot” was initially discovered in 2009 at the Burtele site in northeastern Ethiopia. Its unique arboreal adaptations sparked years of scientific debate. The definitive link to Australopithecus deyiremeda was established through subsequent discoveries at the nearby Woranso-Mille site. Researchers, led by Yohannes Haile-Selassie, uncovered new jawbones containing 12 teeth, dating to the same period. Morphological and isotopic analyses of these dental remains, along with their close proximity to the foot, allowed scientists to confidently assign the foot to the previously named but controversial Australopithecus deyiremeda, solidifying its place in the human family tree.

How does this discovery reshape our understanding of human evolution?

This discovery profoundly challenges the traditional, linear view of human evolution as a “straight ladder” where one species neatly follows another. Instead, it reveals a more complex “family tree” model, demonstrating that multiple hominin species, or “cousins,” coexisted in the same geographical region during the Pliocene epoch. It highlights a period of significant “evolutionary experimentation” with different forms of locomotion, including various adaptations for bipedalism and arboreal life. This newfound diversity suggests that our ancestors explored many paths, making the quest to pinpoint our direct lineage even more intricate and fascinating.

Conclusion: A Richer, More Complex Ancestry

The confirmation of Australopithecus deyiremeda as a distinct species living alongside Lucy is a monumental step in paleoanthropology. It reinforces the idea that the story of human evolution is not a simple, straightforward narrative but a dynamic and diverse saga of multiple species adapting, experimenting, and coexisting in ancient landscapes. This new chapter in our ancestral story encourages us to embrace the complexity of our origins, reminding us that the journey to becoming human involved countless evolutionary paths, many of which remain to be fully uncovered. As scientists continue to explore the fossil-rich grounds of Ethiopia, we anticipate even more groundbreaking revelations that will further enrich our understanding of our remarkable past.