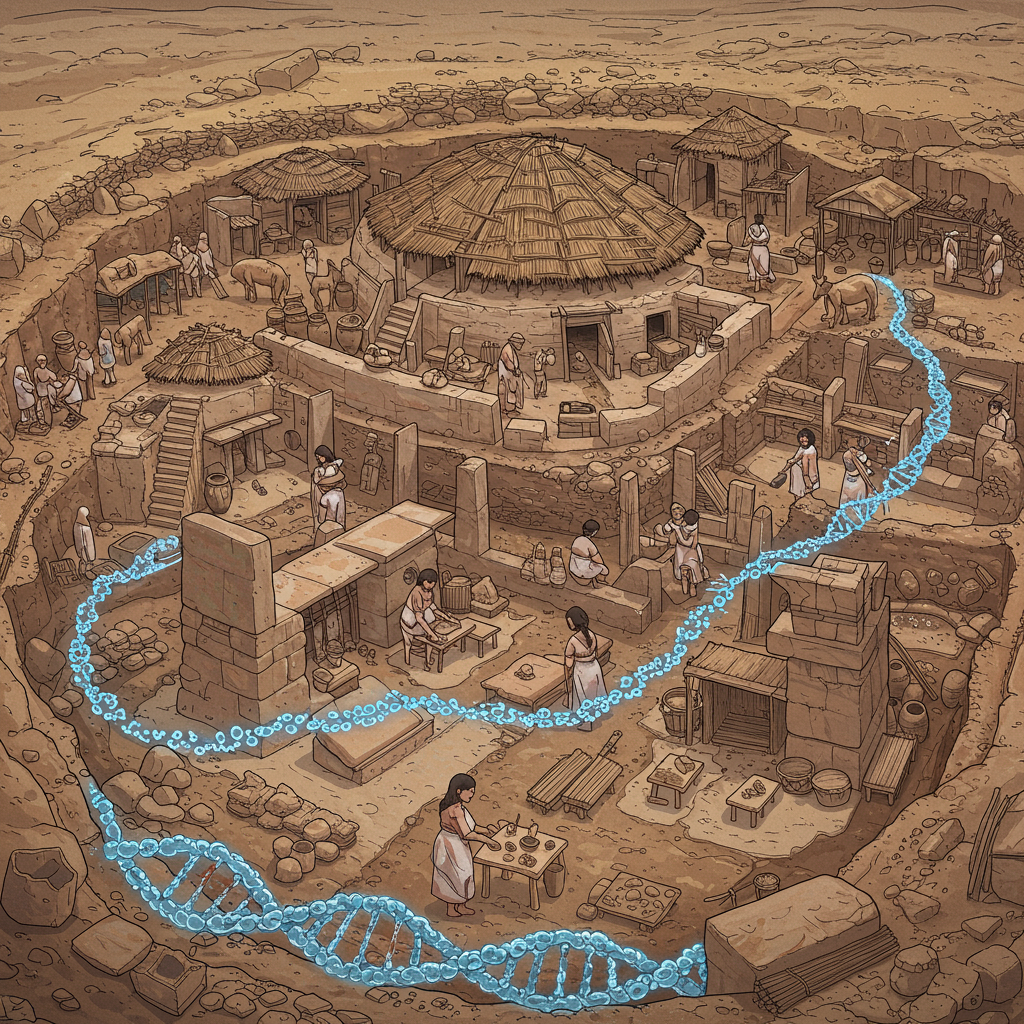

Unlock the secrets of one of the world’s oldest proto-cities! New insights from cutting-edge DNA analysis are overturning long-held assumptions about early human societies. At Çatalhöyük, a remarkable Neolithic settlement in Turkey dating back over 9,000 years, recent discoveries suggest a surprisingly female-centered social structure, challenging the idea that early agricultural communities were inherently dominated by men.

This groundbreaking research, published in the journal Science, dives deep into the genetic makeup of the people who lived in this unique settlement in Anatolia. For years, Çatalhöyük has fascinated archaeologists with its dense, complex layout of mudbrick homes and the lack of obvious social hierarchy indicators. Hints of potential egalitarianism and unique social practices have always been present, but the genetic relationships between inhabitants remained largely unknown until now.

Unprecedented Genetic Snapshot Reveals Maternal Links

The study’s co-lead, Eren Yüncü, a postdoctoral researcher, highlighted Çatalhöyük’s significance as one of the earliest fully agricultural sites and its unusual size for its time. The practice of burying individuals within the settlement’s buildings sparked long-standing questions about kinship and social organization. To find answers, the research team undertook the most comprehensive genomic analysis of a Neolithic Anatolian site to date.

Analyzing ancient DNA extracted from the remains of 131 individuals buried across 35 houses, the scientists peered back across roughly 1,000 years of the settlement’s history, specifically from about 7,000 to 6,200 BCE. This massive dataset, ten times larger than previous studies from the region, allowed for an unprecedented look at generational patterns and relationships.

The primary genetic finding was striking: individuals buried within the same buildings showed strong connections through maternal lines. This suggests that kinship within individual households was often traced through the mother’s side.

Matrilocality: Women Stay, Men Move

Complementing the genetic evidence of maternal lineage was a clear residential pattern known as matrilocality. This term describes a system where adult females tend to remain living in their natal homes, while adult males move to new locations, often upon marriage.

Mehmet Somel, a professor and study co-lead, explained that their findings indicated people residing within buildings were often connected maternally. Conversely, adult males appeared to be the ones moving between different structures. The researchers estimated that female offspring stayed connected to their birth buildings an astounding 70 to 100 percent of the time. This practice stands in stark contrast to patrilocality, the system where females move to live with their partners, which is far more commonly found in archaeological sites globally and was characteristic of later patriarchal societies established across Europe. For instance, a Stone Age burial site in France used for centuries primarily housed males of the same paternal lineage, a clear example of a patrilineal and likely patrilocal system.

Interestingly, immigrants who arrived at Çatalhöyük from outside populations did not show the same strong male or female bias in their residential patterns, suggesting this matrilocal tendency was specific to the core Çatalhöyük community dynamics.

Archaeological Clues Align with Genetic Story

The genetic findings resonate with archaeological evidence that has long fueled speculation about Çatalhöyük’s unique social fabric. The site is famous for its abundance of female fertility figurines, leading some to propose a goddess cult or even a matriarchal society. While a full matriarchy (female political dominance) remains unproven and debated, other clues point towards a significant focus on females.

Analysis of grave goods provided another crucial piece of the puzzle. While adult burials showed no major gender distinctions in accompanying artifacts, there was a notable difference for the young. Female infants and children were buried with approximately five times as many grave goods as their male counterparts. This finding strongly suggests a preferential treatment of young female burials, further supporting the idea of a society that placed particular value on its female members, especially in their early lives. Men and women at Çatalhöyük also seemed to share similar social status and consumed comparable diets.

Changing Households Over a Millennium

The study also uncovered a surprising evolution in the social organization within households across the thousand-year span analyzed. In the earlier periods of the settlement, there was greater genetic kinship among individuals buried within the same houses. This suggests that these early households were often composed of extended families closely related by blood.

However, over time, the genetic links within households became looser. This could indicate a shift towards different forms of social organization, possibly including practices like fostering or adoption becoming more common within the community. Critically, despite this overall decrease in close genetic ties within buildings in later periods, the genetic relationships that did exist still showed a bias towards maternal lines, demonstrating the persistence of this female-centered pattern even as household structures adapted.

Challenging Assumptions About Early Societies

The possibility of an early matriarchy at Çatalhöyük remains an enticing, yet ultimately unresolved, question. The researchers carefully concluded that while the maternal links within buildings are compatible with a matrilineal kinship system (lineage traced through the mother), they do not definitively prove a matriarchal society.

What the study does unequivocally demonstrate is that male-centered practices were not a universal or “inherent characteristic” of the earliest agricultural societies. This finding stands in stark contrast to the clearly patriarchal social systems that became dominant later in Europe and many other parts of the world. It adds to a growing body of evidence from other sites, like the complex hunter-gatherer communities who actively avoided inbreeding, suggesting prehistoric societies were far more diverse and complex than previously assumed, not simply following a single path towards patriarchy or centralized authority as seen in places like early Mesopotamia.

Eren Yüncü noted that the discussion about gender roles and kinship at Çatalhöyük is far from over. The team emphasizes that more research is needed at other Neolithic sites across Anatolia and the Middle East to understand if the patterns observed at Çatalhöyük were unique to this extraordinary settlement or part of a broader regional trend. The journey to fully understand the diverse ways early humans organized themselves is just beginning.

Frequently Asked Questions

What were the main findings of the new Çatalhöyük DNA study?

The study found strong evidence of maternal lines connecting individuals buried within the same houses at Çatalhöyük. It also revealed a pattern of matrilocality, where females tended to remain in their natal homes while males moved between buildings. Additionally, the research showed preferential burial treatment for young females and a shift in household kinship structure over time, though the maternal bias persisted.

How does Çatalhöyük’s social structure compare to other ancient societies?

Çatalhöyük’s matrilocal residence pattern and emphasis on maternal lineage stand in notable contrast to the more common patrilocal systems observed in many other archaeological sites, including later patriarchal societies in Europe where lineage and residence were centered around males. This suggests early agricultural societies were not uniformly structured and highlights the unique social paths early human communities could follow.

If Çatalhöyük was female-centered, does that mean it was a matriarchy?

Not necessarily. The study indicates a matrilineal kinship system (lineage traced through mothers) and matrilocality (females staying in natal homes), which are compatible with a female-centered society. However, it does not definitively prove a matriarchy, which implies female political dominance. While women may have held significant status, the exact nature of political power and gender roles remains a subject of ongoing debate and requires further investigation.