The story of our mental health is often written in the enduring pathways of our brains. For those struggling with depression and anxiety, these pathways can become deeply etched, self-reinforcing “ruts” that promote negative thought patterns, fear, and avoidance. While traditional treatments like talk therapy and SSRI medications can help nudge individuals out of these ruts, the gains can sometimes be difficult to maintain, as the underlying neural configurations remain largely unchanged.

What if there was a way to temporarily “reset” these rigid neural pathways, allowing for the possibility of building healthier connections? Emerging research suggests that psilocybin, the psychoactive compound found in “magic mushrooms,” might offer just such a capability, potentially after just a single therapeutic dose.

Exciting data from recent clinical trials is shedding light on this possibility. One notable Phase 2 trial, published in the journal CANCER, investigated the impact of a single 25 mg dose of psilocybin in 30 participants diagnosed with both cancer and major depressive disorder. A key strength of this study was its long-term follow-up, tracking participants for two years – a duration often missing in earlier psilocybin research, leaving questions about the durability of effects.

Study Design and Approach

The intervention spanned eight weeks. Participants underwent four initial psychotherapy sessions to prepare for the experience. They then received the single psilocybin dose in a carefully monitored setting, remaining for 6-7 hours. Following the session, they engaged in four more integration therapy visits designed to help process the psychedelic experience and its insights. Mental health was assessed at multiple points using standardized scales, including the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS).

Significant and Sustained Results

The findings from the CANCER study were remarkable. At the end of the initial 8-week intervention period, participants showed an average 20-point reduction in their MADRS scores from baseline – a dramatic improvement. While this specific trial did not include a placebo group, the magnitude of this reduction is significant when compared to meta-analyses of SSRI studies, which typically show an average reduction of around 3 points on the MADRS scale compared to placebo. Previous placebo-controlled trials, such as a 2022 study in The New England Journal of Medicine involving patients with treatment-resistant depression, have also demonstrated clear efficacy, showing a 12-point improvement in the psilocybin group versus 5.5 points for placebo using the same scale.

Perhaps most compelling were the long-term outcomes. At the 2-year follow-up mark, available for 28 participants, the profound relief persisted for a substantial portion of the group. More than half of the participants (53.6%) maintained a significant reduction in their depression symptoms compared to their baseline scores, with an average drop of 15 points at this 2-year point. Strikingly, half of the evaluated patients (50%) were classified as being in remission from major depressive disorder two years after receiving just one dose of psilocybin combined with therapy. Anxiety symptoms also showed sustained improvement, with nearly 43% of participants reporting lasting relief at the two-year follow-up.

This level of sustained relief from a single treatment session, especially in patients facing the significant stress of a cancer diagnosis, offers a compelling contrast to the daily dosing and often more modest long-term effects seen with traditional antidepressant medications. Researchers are describing this approach as a potential “paradigm-changing alternative” for mental health treatment.

Understanding the Potential Mechanism

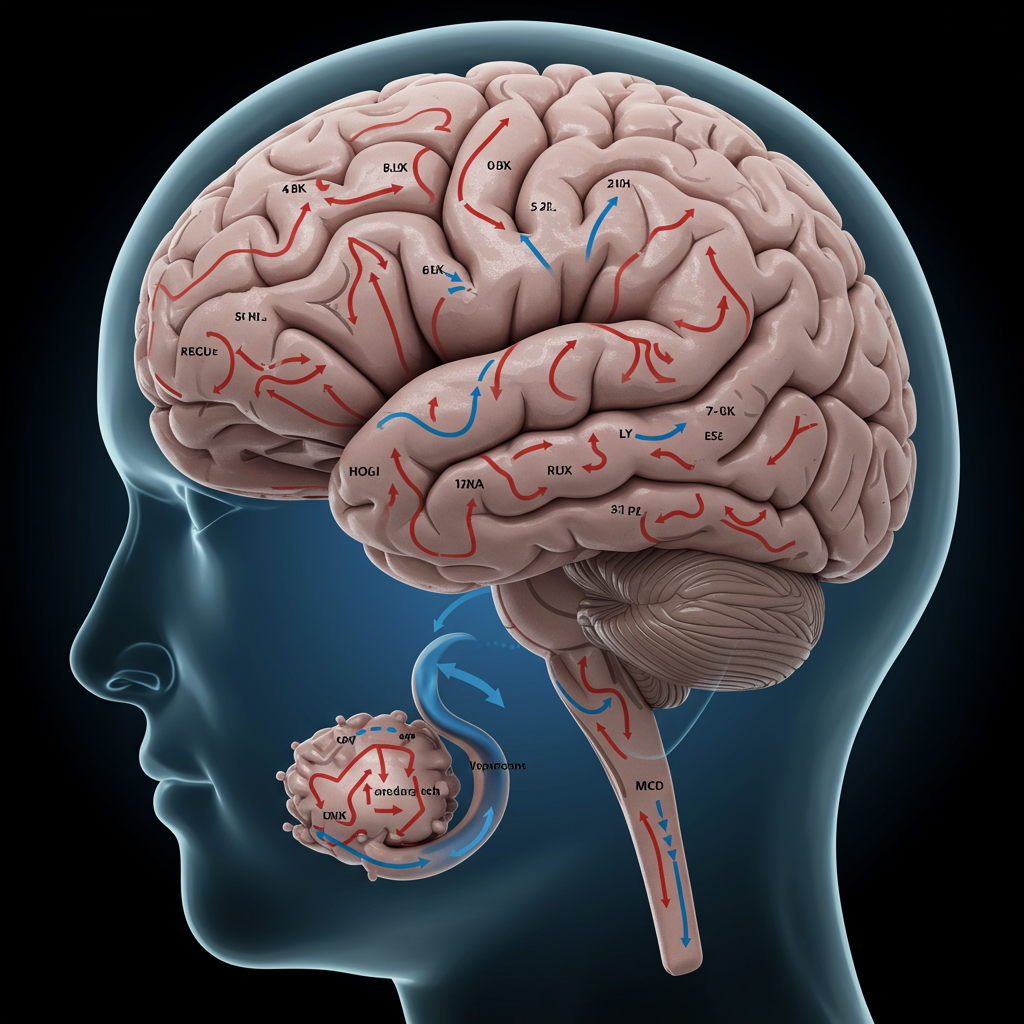

How can a single dose have such a lasting impact? One leading theory centers on psilocybin’s interaction with the brain’s serotonin 2A receptor. This receptor is also the target of other classic psychedelics like LSD and mescaline and is implicated in conditions like schizophrenia.

Researchers suggest that psilocybin acts as a “psychoplastogen” – a compound that rapidly increases neural plasticity. In essence, it may temporarily loosen the rigid structure of established neural networks, particularly those involved in entrenched negative thinking and emotional patterns. This increased flexibility could allow for the breakdown of maladaptive connections and the formation of new, healthier pathways. Think of it as temporarily “loosening the soil” of the brain, making it more receptive to change.

This potential mechanism also highlights the critical role of the accompanying psychotherapy. While the psilocybin may create the state of increased plasticity and offer new perspectives, the therapy sessions before and after the experience are crucial for helping individuals process insights, integrate the experience, and actively work towards building and reinforcing those healthier neural connections. The drug is not a standalone cure but a tool used within a structured therapeutic process.

Future Directions and Important Caveats

While these results, particularly the sustained effects demonstrated in the CANCER trial, are highly promising, the research is still relatively early. Limitations include the small sample size of the long-term follow-up and the specific population studied (cancer patients with depression).

Larger, randomized, placebo-controlled trials are underway to further evaluate psilocybin’s efficacy in diverse populations and conditions. An ongoing trial mentioned by researchers from the CANCER study is specifically comparing the effects of up to two doses of psilocybin versus placebo in cancer patients with depression and anxiety, aiming to see if repeat dosing can further increase remission rates.

It is crucial to remember that psilocybin is a powerful compound, and its therapeutic use requires administration in a controlled setting under the supervision of experienced medical and psychological professionals. It is not a panacea for all mental health issues, and potential risks exist.

Nevertheless, the data continues to build a compelling case for supervised psilocybin therapy as a potential new frontier in treating debilitating conditions like depression, offering the hope of profound, lasting relief from a single session by targeting the very structure of the brain’s entrenched patterns.