Recent research highlights a surprising distinction in the lungs of individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). A new analysis found that lung tissue from people with COPD contained more than triple the amount of soot-like carbon particles compared to similar tissue from smokers who did not have COPD.

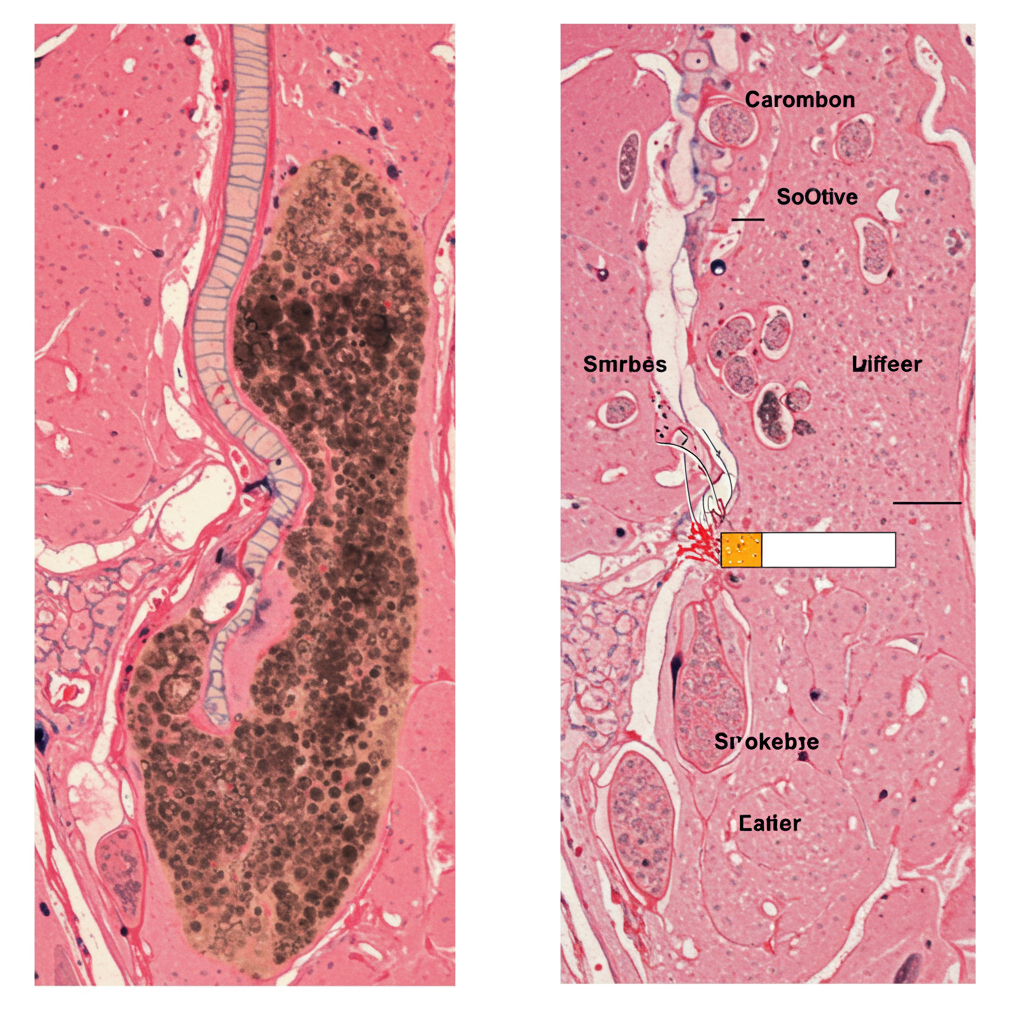

The study, conducted by researchers at the University of Manchester in the UK, analyzed lung tissue samples from patients undergoing surgery. They focused on alveolar macrophages, a type of immune cell in the lungs specifically tasked with clearing away inhaled dust, particles, and microorganisms.

The key finding was striking: these particle-clearing cells in COPD patients held significantly more carbon than those in smokers without the disease. Furthermore, the macrophages containing visible carbon deposits were noticeably larger than those without. Patients with larger amounts of carbon buildup in these lung cells also showed poorer lung function, as measured by standard tests like FEV1%.

Laboratory experiments supported these findings, demonstrating that exposing macrophages to carbon particles caused them to enlarge and produce higher levels of inflammatory proteins.

This research suggests that the extensive carbon buildup observed in COPD lungs isn’t solely a direct consequence of the amount smoked. Instead, it points to a potential difference in how the lungs of individuals with COPD handle inhaled particles. It’s possible their macrophages are less efficient at clearing carbon, or that greater exposure to particulate matter from sources like cigarette smoke, diesel exhaust, and polluted air contributes more significantly to disease development in susceptible individuals.

Understanding COPD: A Complex Picture

This finding adds another layer to the complex understanding of COPD. While smoking is the leading cause and a major risk factor, research continues to uncover other crucial pieces of the puzzle.

For instance, studies funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) have identified abnormal lung development, specifically having smaller airways relative to overall lung size (a condition called dysanapsis), as a significant risk factor. This structural difference may help explain why some non-smokers develop COPD and why some heavy smokers do not. Individuals starting with smaller airways may reach the threshold for symptomatic COPD as lung function naturally declines with age, even without extensive damage from smoking. Conversely, those with larger airways may have a greater “reserve” allowing them to tolerate more damage before developing severe symptoms.

Lifestyle factors, including diet, are also being explored. Recent research suggests that dietary patterns, such as adherence to a low-carbohydrate diet, may be associated with a lower prevalence of COPD. One theory is that diets higher in carbohydrates lead to greater carbon dioxide production during metabolism, increasing the respiratory burden on already compromised lungs.

Putting the Pieces Together

The picture emerging from these diverse studies underscores that COPD is not a single-cause disease. While avoiding smoking and exposure to air pollution remains paramount, research into factors like impaired particle clearance, lung developmental patterns, and lifestyle choices like diet is vital. These findings help explain the disease’s variability and open doors for new approaches to prevention, earlier diagnosis, and personalized management strategies for a broader range of patients.