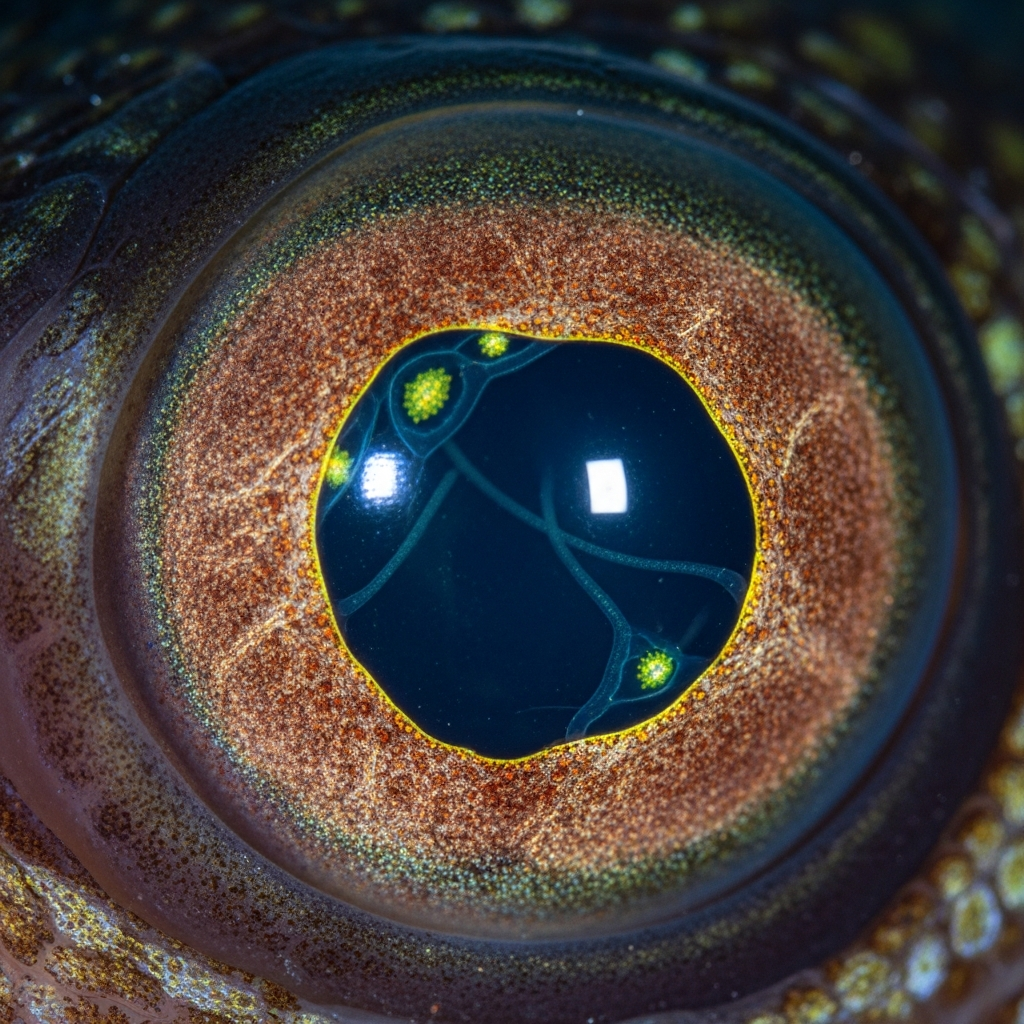

Deep in the perpetually dim twilight zones of the Red Sea, scientists have uncovered an astonishing biological secret that threatens to rewrite over a century of established understanding about how vertebrate eyes work. Researchers studying tiny deep-sea fish have identified revolutionary hybrid eye cells. These cells possess characteristics previously thought to be mutually exclusive, blending features of both rods and cones in a way never before seen in the animal kingdom. This groundbreaking discovery dramatically expands our knowledge of vision and the incredible adaptability of life in Earth’s most extreme environments.

For generations, biology textbooks have taught a clear, distinct division in how vertebrates perceive light. Rods, specialized for detecting dim light and motion, allow us to see in low-light conditions. Cones, on the other hand, are responsible for sharp vision and distinguishing colors in brighter light. This two-part system has been a foundational principle of vision science. However, new research published in Science Advances reveals that some deep-sea dwellers defy this rigid classification, offering a fresh perspective on the flexibility of evolutionary adaptation.

Unraveling the Deep-Sea Vision Mystery

The pivotal discovery emerged from studying the larvae of three particular Red Sea fish species: the hatchetfish (Maurolicus mucronatus), a lightfish (Vinciguerria mabahiss), and a lanternfish (Benthosema pterotum). These diminutive creatures, measuring only one to three inches as adults, inhabit depths where sunlight barely penetrates, creating an eternal twilight. It’s in these challenging conditions, between 65 and 650 feet below the surface, that their unique visual systems thrive.

Lily Fogg, a marine biology postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki in Finland and lead author of the study, explained the core finding. “These cells look like rods – long, cylindrical and optimized to catch as many light particles – photons – as possible. But they use the molecular machinery of cones, switching on genes usually found only in cones,” Fogg stated. This “mix-and-match” approach allows the fish to excel in dim light while potentially retaining some color processing capabilities. Interestingly, while hatchetfish maintain these hybrid cells throughout their lives, the lightfish and lanternfish transition to more conventional rod-cone systems as they mature.

A Flexible Retina: Challenging Old Paradigms

This finding profoundly challenges the long-held notion that rods and cones are fixed, clearly separated cell types. It suggests that the retina, the eye’s light-detecting membrane that converts visual information into brain signals, is far more adaptable and evolutionarily flexible than previously believed. Fogg emphasized, “Our results challenge the longstanding idea that rods and cones are two fixed, clearly separated cell types. Instead, we show that photoreceptors can blend structural and molecular features in unexpected ways. This suggests that vertebrate visual systems are more flexible and evolutionarily adaptable than previously thought.”

Fabio Cortesi, a senior researcher and marine biologist at the University of Queensland in Australia, highlighted the broader implications of this biological flexibility. “It is a very cool finding that shows that biology does not fit neatly into boxes,” Cortesi commented. He even speculated that such hybrid cells might be more common across various vertebrates, including terrestrial species, suggesting a potential paradigm shift in how we understand vision across the animal kingdom. This discovery underscores the ocean’s remarkable capacity to surprise scientists and broaden our understanding of life itself.

Beyond Vision: Remarkable Deep-Sea Adaptations

The innovative eye cells are just one facet of these deep-sea fish’s incredible toolkit for survival. These species also possess another fascinating adaptation: bioluminescence. They generate their own blue-green light using specialized organs, primarily located on their undersides. This self-produced glow remarkably matches the faint sunlight filtering down from above. This sophisticated camouflage technique, known as counterillumination, allows them to blend seamlessly with their environment, effectively hiding from predators lurking below.

These tiny fish, despite their size, play an outsized role in the marine ecosystem. Cortesi stressed their ecological importance: “Small fish like these fuel the open ocean.” They form a crucial link in the food web, serving as primary sustenance for a multitude of larger predatory fish, including tuna and marlin. Marine mammals such as dolphins and whales, and various marine birds, also rely on them as a vital food source. Furthermore, these species participate in one of nature’s most extensive daily migrations, swimming toward the surface each night to feed in nutrient-rich waters before returning to depths of 650 to 3,280 feet during daylight hours to escape predation.

The Ocean’s Enduring Mysteries and Revolutionary Discoveries

The deep sea remains an immense, largely unexplored frontier, a “mystery box” with endless potential for scientific revelations. The discovery of these hybrid eye cells is a powerful testament to the ocean’s capacity to challenge and expand our scientific understanding, much like other unexpected marine finds throughout history.

For instance, the accidental study of the humble anglerfish in the late 1970s, chosen merely because it was cold-blooded and exempt from research restrictions, led to the groundbreaking discovery of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1). This hormone, initially found in a “trash fish,” has since revolutionized the treatment of obesity and diabetes, impacting billions worldwide and proving that profound medical breakthroughs can emerge from the most unlikely corners of the natural world.

Similarly, the Greenland shark, residing in the frigid North Atlantic, has captivated scientists with its astonishing longevity, potentially living for over 500 years. This makes it the longest-living vertebrate on Earth. Researchers are now studying its unique biology to uncover secrets to extreme aging and disease resistance, hoping to find insights applicable to human health. Each new finding from the deep sea, whether a novel visual system, a medicinal compound, or a mechanism for extreme longevity, reinforces the idea that the ocean holds keys to fundamental biological processes we are only just beginning to comprehend.

Ongoing exploration continues to reveal the vast biodiversity hidden beneath the waves. Recent collaborative research, for example, has formally described three new species of deep-sea snailfish from the Monterey Canyon. These discoveries, like the bumpy snailfish, dark snailfish, and sleek snailfish, highlight how much remains unknown about life on Earth, even as our planet faces growing threats from climate change and human activities. The deep sea is not just a place for curiosity; it’s a vital reservoir of biological innovation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What makes the newly discovered deep-sea fish eye cells so revolutionary?

The deep-sea fish eye cells are revolutionary because they defy the traditional biological understanding of vertebrate vision. For over a century, scientists believed that vision relied on two distinct cell types: rods for low light and cones for bright light and color. These newly discovered cells are “hybrid photoreceptors” that combine the physical structure of rods (optimized for catching many light particles) with the genetic and molecular machinery of cones. This blend allows them to function effectively in the deep ocean’s perpetual twilight, challenging the fixed nature of visual cell types and demonstrating unexpected evolutionary flexibility in the retina.

Which deep-sea fish species possess these unique hybrid eye cells?

The groundbreaking research focused on the larvae of three specific deep-sea fish species found in the Red Sea. These include a hatchetfish (Maurolicus mucronatus), a lightfish (Vinciguerria mabahiss), and a lanternfish (Benthosema pterotum). While the hatchetfish maintains these hybrid rod-cone cells throughout its entire life, the lightfish and lanternfish transition to more conventional rod-cone vision systems as they mature into adults. These tiny fish, measuring only 1-3 inches, inhabit dimly lit ocean depths between 65 and 650 feet.

How might this discovery about fish vision impact future biological research or human understanding?

This discovery has profound implications for future biological research. It suggests that the vertebrate visual system, including that of humans, is far more adaptable and flexible than previously thought, potentially leading to a re-evaluation of how our own retinas function and evolve. The finding that “biology does not fit neatly into boxes” opens doors for exploring hybrid cell types in other species, even terrestrial ones. It also underscores the importance of deep-sea exploration, as the ocean continues to be a “mystery box” yielding unexpected biological innovations that can revolutionize fields from medicine (like the GLP-1 discovery from anglerfish) to our fundamental understanding of life itself.

The remarkable flexibility of life in the deep sea serves as a powerful reminder of the vast potential for scientific discovery that remains hidden within Earth’s oceans. As Fabio Cortesi concludes, we must “look after this habitat with the utmost care to make sure future generations can continue to marvel at its wonders.” Protecting these pristine environments is crucial not just for biodiversity, but for the untold scientific breakthroughs they still hold.