Could the way you live dramatically shape how you age? For decades, scientists believed that a specific type of <a href="https://news.quantosei.com/2025/07/06/breakthrough-study-links-vaccines-to-reduced-alzheimers-risk/” title=”Proven Shots May Slash Alzheimer's & Dementia Risk by Up To 30%”>inflammation, dubbed “inflammaging,” was an unavoidable part of growing older, quietly fueling chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and dementia. This view held that as years passed, your immune system would naturally become overactive, like an alarm stuck on, causing low-level inflammation that wears down the body.

But groundbreaking new research is turning that idea on its head. A major study suggests that this age-related chronic inflammation might not be universal after all. Instead, it could largely be a consequence of modern living, challenging our fundamental understanding of ageing itself.

What is Inflammaging and Why Does it Matter?

Think of inflammation as your body’s first responder. When you get a cut or catch a cold, inflammation is the crucial process that sends immune cells to heal and fight off invaders. This is acute, temporary inflammation – a necessary function for survival.

Inflammaging, however, is different. It’s chronic, low-grade inflammation that persists over time without an obvious injury or infection. It’s like the immune system is constantly humming at a low frequency, leading to cellular stress and damage throughout the body. Scientists have long linked this persistent state to a higher risk of many conditions we associate with ageing, from cardiovascular problems and metabolic disorders to cognitive decline.

A Study That Changes the Narrative

Published in the journal Nature Aging, the research looked at inflammation patterns in blood samples from over 2,800 people across four vastly different global communities. The study deliberately compared groups from modern, industrialised settings – older adults in Italy and Singapore – with Indigenous populations living more traditional lifestyles: the Tsimane people of the Bolivian Amazon and the Orang Asli in Malaysia’s forests.

The goal was to see if the pattern of specific inflammatory molecules (cytokines and others like C-reactive protein and tumor necrosis factor) rising predictably with age, which had been observed in earlier studies primarily in Western populations, was consistent across these diverse groups. Researchers analyzed a wide range of these markers in blood samples to capture a comprehensive picture of immune activity.

Contrasting Worlds, Contrasting Inflammation

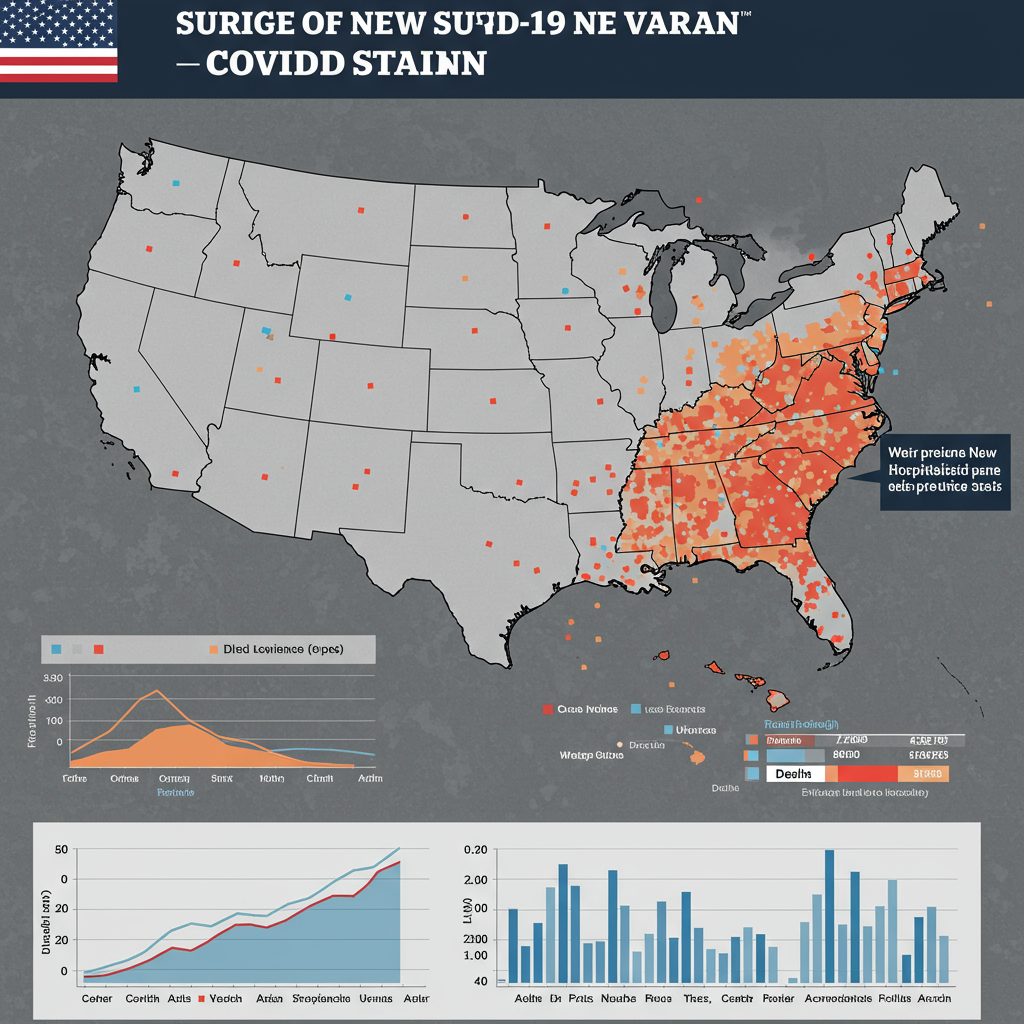

The findings were striking. In the participants from Italy and Singapore, the expected inflammaging pattern was clearly present. As individuals aged, the levels of inflammatory markers in their blood generally increased together, and these higher levels were associated with a greater risk of developing common age-related chronic diseases, such as kidney and heart disease. This aligned with the long-held view of inflammaging.

However, the picture was completely different in the Tsimane and Orang Asli groups. In these populations, the inflammatory molecules did not consistently rise with age. Crucially, they were not strongly linked to the same age-related diseases commonly seen in the industrialised nations. This was particularly notable among the Tsimane, who, despite facing high rates of infections from parasites and pathogens which cause significant acute inflammation, showed very low rates of heart disease, diabetes, and dementia. Their immune systems were clearly active, but the pattern of chronic, disease-linked inflammation associated with ageing in the other groups was absent.

Is Modern Lifestyle the Missing Link?

These results strongly suggest that inflammaging, at least as measured in the bloodstream, might not be a universal biological fate of ageing. Instead, it could be a consequence of the environments and lifestyles prevalent in modern, industrialised societies. Factors like diets high in processed foods and calories, sedentary lifestyles, chronic stress, and potentially even reduced exposure to diverse microbes and infections early in life could be driving this persistent, low-grade inflammation.

The theory is that our evolutionary biology, adapted over millennia to environments with different challenges (like frequent infections but lower caloric excess and higher physical activity), is mismatched with the contemporary world. Our immune systems, instead of being challenged by acute threats they are built to handle, may become dysregulated by chronic stressors and inputs from our modern environment, leading to inappropriate, persistent activation that manifests as inflammaging. Research has shown, for instance, that chronic stress and poor sleep – often hallmarks of modern life – can disrupt hormonal balance and contribute to inflammation, impacting metabolic health and potentially weight gain over time.

Inflammation: A Complex Player in Health

It’s important to understand that inflammation itself isn’t inherently bad; it’s a vital immune response. The study highlights that traditional populations like the Tsimane experience high levels of acute inflammation due to infections, which is a healthy and necessary immune function. The issue seems to be with the chronic, low-grade inflammation characteristic of inflammaging in modern societies.

Furthermore, inflammation plays complex roles in other health contexts. For example, research into conditions like HIV shows that even with effective treatment, people with HIV can experience ongoing, low-level immune activation. This chronic inflammatory state is linked to a higher risk of developing age-related conditions compared to their peers without HIV. This underscores that inflammation can be driven by various factors – pathogens, lifestyle, underlying health conditions – and its link to health outcomes is not solely tied to chronological age or a single mechanism. Scientists are even exploring ways to measure biological age more precisely using markers like ‘epigenetic clocks’ that track DNA changes influenced by factors like disease and environment, adding another layer to understanding how health states impact “ageing.”

Why These Findings Are Crucial

If confirmed by future research, these findings have profound implications for how we approach health and ageing:

Rethinking Diagnostics: Biomarkers currently used to identify and monitor inflammaging, largely validated in European or Asian populations, may not be reliable indicators in other ethnic groups or those living different lifestyles. We may need new tools or approaches to assess inflammation risk globally.

Targeting Interventions: Lifestyle interventions (diet, exercise, stress reduction) and potential future drugs aimed at reducing chronic inflammation might have different impacts or effectiveness depending on a population’s environment and baseline immune state. What works for someone in a city might be less relevant for someone living a traditional lifestyle.

Addressing Research Bias: A vast majority of health research is conducted in wealthy, industrialised nations. This study is a powerful reminder that findings from these populations cannot simply be assumed to apply worldwide. We need much more inclusive research involving diverse communities to build a truly global understanding of human health and ageing.

Looking Ahead and Taking Action

The researchers behind this Nature Aging study emphasize that this is just the beginning. They call for deeper investigation, perhaps using advanced technologies that can detect inflammation not just circulating in the blood, but within specific tissues and cells where age-related changes truly unfold. Most importantly, they urge the scientific community to embrace more inclusive research, spanning the incredible diversity of human experience, beyond the urbanized corners of the world.

Ultimately, this study offers a compelling message: the biology of ageing, particularly the role of inflammation, is likely far more flexible and influenced by our environment and lifestyle than previously thought. What we assumed was an inevitable decline may, in part, be a consequence of how we live. This provides both a challenge and an opportunity.

Actionable Steps for Your Health

While research continues, the findings reinforce the power of lifestyle. Reducing chronic inflammation through positive habits can potentially impact your long-term health:

Prioritize a Nutrient-Rich Diet: Focus on whole, unprocessed foods – abundant fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Limit processed foods, sugary drinks, and excessive unhealthy fats known to promote inflammation.

Stay Physically Active: Regular exercise is a powerful anti-inflammatory. Aim for a mix of cardiovascular activity and strength training.

Manage Stress: Chronic stress is a major contributor to inflammation. Incorporate stress-reducing practices like meditation, yoga, spending time in nature, or pursuing hobbies.

Ensure Sufficient Sleep: Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. Poor sleep disrupts hormonal balance and increases inflammation.

Avoid Smoking and Limit Alcohol: Both are significant drivers of inflammation and chronic disease.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is inflammaging and how is this study changing our understanding?

Inflammaging refers to the chronic, low-level inflammation believed to increase with age and contribute to age-related diseases like heart disease and dementia. Traditionally, it was seen as an inevitable part of biological ageing. This new study published in Nature Aging challenges that by showing this specific pattern of rising inflammation markers with age is prominent in people from modern industrialised societies but largely absent in traditional Indigenous populations, suggesting it may not be a universal process but potentially linked to lifestyle and environment.

Where can I find more information about lifestyle changes to reduce chronic inflammation?

Many reputable health organizations provide guidance on lifestyle interventions for reducing inflammation. Look for resources from institutions like Harvard Health, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), or your local health authority. These resources often provide detailed information on anti-inflammatory diets focusing on whole foods, the benefits of regular exercise, stress management techniques, and the importance of sufficient sleep, aligning with the findings suggesting lifestyle impacts inflammation.

Should I get tested for inflammation levels as I age?

Common inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) are sometimes included in routine blood tests and can indicate general inflammation levels. However, this study highlights that the meaning and predictability of these markers might differ depending on your lifestyle and background. While monitoring inflammation can be useful as part of a broader health assessment, especially if you have risk factors for chronic disease, interpreting the results requires professional medical advice that considers your individual context. The study suggests current biomarkers might not universally capture the full picture of age-related inflammation.

Conclusion

The idea that age-related chronic inflammation might be a consequence of how we live, rather than an unavoidable outcome of time, is a powerful one. This landmark study underscores the incredible plasticity of human biology and the profound impact of our environment and lifestyle on the ageing process. It serves as a vital call for more diverse, comprehensive research and empowers individuals to recognize the potential role their daily habits play in shaping their long-term health trajectory. Ageing might not be the same everywhere, and understanding why could unlock new ways to promote healthy longevity worldwide.