Navigating the world of nutrition advice can feel overwhelming, with new studies constantly emerging. A recent meta-analysis from the University of Washington has sparked significant discussion, suggesting a striking link between even small, regular amounts of processed foods and increased risk for several chronic diseases. The findings specifically target processed meats, sugary drinks, and trans fatty acids, concluding that there may be “no safe level” for habitual consumption of these items when it comes to health.

Published in the journal Nature Medicine, this research synthesized data from 77 different studies. The goal was to gain a clearer picture of how varying consumption levels of these common food groups relate to the likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease (the most prevalent type of heart disease), and colorectal cancer.

Unpacking the Study’s Key Findings

The research team, led by Demewoz Haile, a scientist at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, found consistent associations across the analyzed studies. According to Haile, consuming even seemingly minor quantities of these foods and beverages on a daily basis appears linked to elevated health risks.

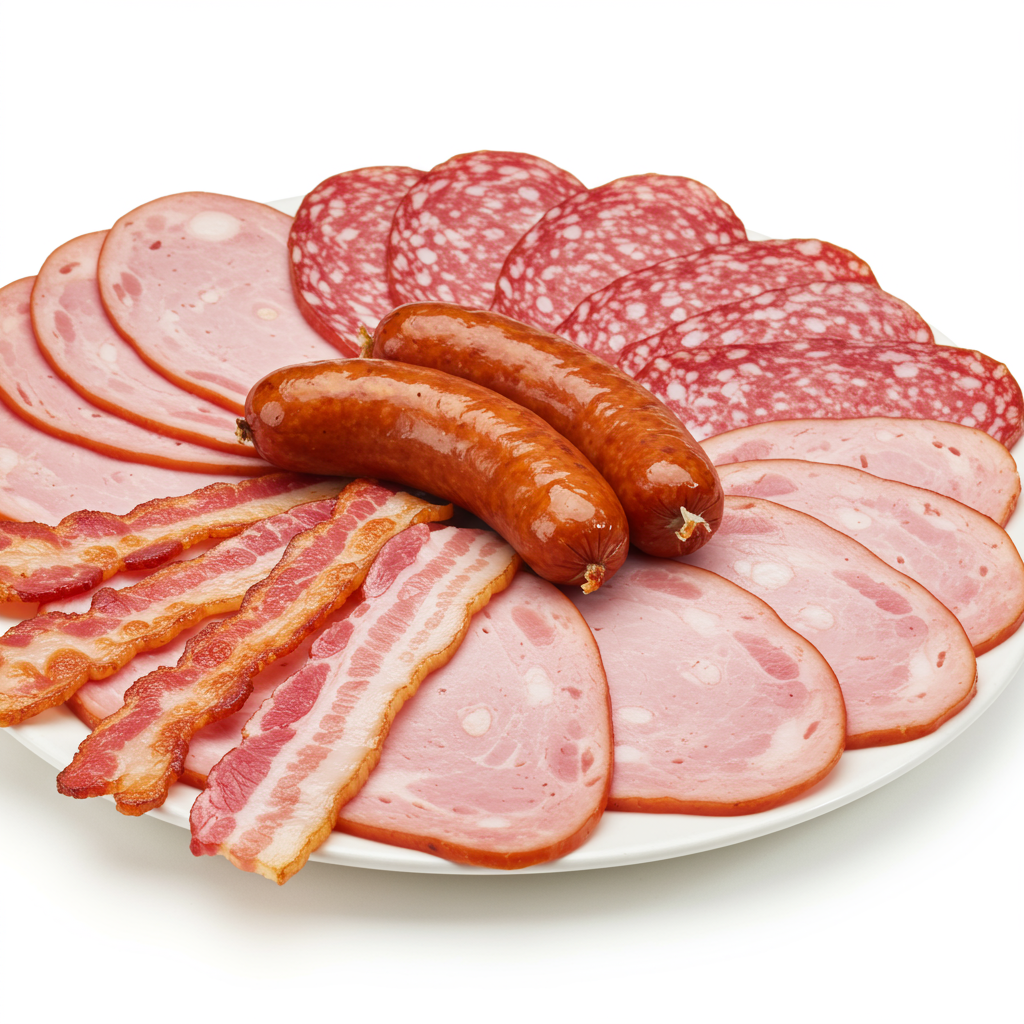

Processed Meat: Small Amounts, Bigger Risks?

Processed meats stood out with clear associations. The meta-analysis indicated that habitually eating between 0.6 and 57 grams per day was tied to an 11% higher probability of developing type 2 diabetes. For colorectal cancer, consuming 0.78 to 55 grams daily was associated with a 7% increased risk. To put these numbers in perspective, a standard hot dog typically contains around 50 grams of processed meat. This suggests that eating just one hot dog a day could potentially fall within the range linked to these increased risks.

Processed meat, as defined in the study, includes any meat preserved through smoking, curing, salting, or the addition of chemical preservatives. This category encompasses a wide range of products common in many diets.

Sugar and Trans Fats Also Under Scrutiny

Beyond processed meats, the study also highlighted concerns around sugar-sweetened beverages and trans fatty acids.

Drinking between 1.5 and 390 grams of sugary drinks per day was linked to an 8% higher risk of type 2 diabetes. When looking at ischemic heart disease, consuming between 0 and 365 grams per day was associated with a 2% increase in risk.

Trans fatty acids, often found in partially hydrogenated oils, were also analyzed. The study found that when these fats constituted just 0.25% to 2.56% of daily energy intake, they were linked to a 3% greater risk of ischemic heart disease. Common sources of trans fats include certain crackers, cookies, baked goods, frozen pizzas, coffee creamers, refrigerated doughs, some margarines, and many fast food items.

Why This Study Matters

Previous research has established links between processed foods and poor health outcomes. However, the authors emphasize that their meta-analysis utilized more recent studies and employed advanced analytical methods. This allowed them to objectively assess the strength of the evidence and, importantly, to evaluate the shape of the relationship – specifically, whether risks appeared only at high consumption levels or across the board.

Haile noted that their analysis revealed the strongest associations at lower exposure levels. This implies that even small, regular servings of these items might increase the risk of adverse health outcomes over time, reinforcing the “no safe level” conclusion regarding habitual consumption.

Given these findings, the researchers’ advice aligns with major public health organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). They recommend limiting or eliminating consumption of processed meats, sugary drinks, and artificial trans fats as much as possible. Individuals who eat these foods regularly, even in small quantities, should be aware of the potential for increased chronic disease risk.

Acknowledging Study Limitations and Expert Perspectives

While the study presents compelling associations, the authors and external experts are quick to point out important caveats.

Challenges in Dietary Assessment

One primary limitation highlighted by the study authors themselves is the method used to assess dietary intake in most of the included studies. Food frequency questionnaires were commonly used. While practical, these questionnaires can introduce measurement errors because participants might struggle to accurately recall their long-term eating habits. Additionally, some studies only recorded consumption at the beginning, which might not reflect participants’ actual diets over the entire study period.

The meta-analysis also focused on a limited set of health outcomes for each dietary factor. This means the study might potentially underestimate the total negative health impact associated with these food groups. The researchers also noted significant variability among the existing literature, indicating that more high-quality research is still needed to strengthen the evidence base and reduce uncertainty surrounding these links.

Associations vs. Causation: A Critical Distinction

Dr. Nick Norwitz, a Harvard-educated researcher not involved in the study, acknowledged the consistent association found between higher processed meat intake and worse health outcomes. However, he stressed a crucial point in interpreting such studies: “These are associations — not necessarily causal relationships.” Observational studies like those included in the meta-analysis can show a link, but they don’t definitively prove that the processed food causes the disease. People who eat more processed foods might also have other lifestyle factors that contribute to poor health, like less exercise, higher calorie intake overall, or lower consumption of fruits and vegetables.

Norwitz also echoed the authors’ point about the quality of evidence, noting that the meta-analysis itself graded the evidence as “weak” in some areas. He added that lumping together diverse foods within a single category, like “processed meats,” can be problematic. Different processing methods and ingredients likely have varied biological effects.

Ultimately, while acknowledging that processed meat could contribute to poor health, Norwitz suggested that other dietary items commonly consumed might be more metabolically damaging. He offered a relatable example: “the office donut or bottle of soda is almost certainly doing more metabolic damage than a slice of deli turkey.” This perspective emphasizes the importance of considering the overall diet rather than focusing on just one type of food in isolation.

An industry perspective was also provided by a spokesperson from the American Association of Meat Processors (AAMP). They pointed out that the study’s abstract mentioned “weak relationships or inconsistent input evidence” and the need for more research. They also raised questions about how “processed meat” was specifically defined in the study and whether the potential health benefits of nutrients and protein found in meat were considered alongside the supposed risks.

The study authors did clarify their definition of processed meat, noting it included preservation methods like smoking, curing, salting, or adding chemical preservatives.

Making Informed Food Choices

Understanding the nuances of nutritional science is key to making empowered choices. While this study highlights potential risks associated with regularly consuming processed meats, sugary drinks, and trans fats, it exists within a larger body of research. The consensus among major health organizations is generally to prioritize whole, unprocessed foods, lean proteins, fruits, vegetables, and healthy fats while limiting intake of highly processed items.

The “no safe level” message from the study’s lead author serves as a strong recommendation to minimize consumption of these particular categories if possible. Even small, incremental changes to your diet can add up over time and potentially impact long-term health outcomes. Focusing on dietary patterns that emphasize nutrient density and minimize processing is a strategy widely supported by nutritional science.

Frequently Asked Questions

What specific processed foods did the University of Washington study link to increased disease risk?

The meta-analysis specifically identified processed meats (like hot dogs, bacon, deli meats), sugar-sweetened beverages (soda, fruit drinks), and trans fatty acids (often found in baked goods, fried foods, certain margarines) as being associated with increased risk for chronic diseases, even at low consumption levels.

Does eating just one hot dog a day really mean I will get sick?

The study found that habitually consuming amounts of processed meat comparable to one hot dog (around 50 grams) was linked to an increased likelihood or higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes (11% increase) and colorectal cancer (7% increase). This indicates an association, not a guarantee. Many factors influence disease risk, including genetics, overall diet, physical activity, and lifestyle. The study suggests reducing consumption as a way to potentially lower risk.

What are the main limitations of studies like this one linking diet to disease?

Studies like this meta-analysis often rely on participants reporting their food intake, typically using questionnaires, which can lead to inaccuracies due to recall bias. They also show associations between diet and disease, which doesn’t definitively prove that the food causes the disease; other lifestyle factors might be involved. Additionally, these studies sometimes group diverse foods into broad categories, potentially overlooking differences in processing methods and their effects.

Conclusion

The University of Washington meta-analysis adds to the growing body of evidence suggesting that regularly consuming processed meats, sugary drinks, and trans fats, even in small quantities, may elevate the risk of developing chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes, colorectal cancer, and heart disease. While the study has limitations common to nutritional research and experts highlight the distinction between association and causation, the findings align with widely accepted dietary advice. Reducing or eliminating these specific food groups from your regular diet, in favor of whole, nutrient-dense options, remains a sensible strategy supported by public health recommendations aimed at improving long-term health. Making informed choices about what you eat is a powerful step towards managing your personal health profile.