Cutting-edge archaeological research has uncovered compelling evidence suggesting neanderthals were far more sophisticated than previously believed, operating what scientists are calling a “fat factory” in what is now Germany around 125,000 years ago. This remarkable discovery reveals our closest extinct relatives developed complex, labor-intensive methods to extract vital grease and marrow from animal bones. Published in the journal Science (or Science Advances as some sources indicate), the findings push back the timeline for advanced resource management strategies by roughly 100,000 years, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of these ancient hominins.

Unearthing a Prehistoric Processing Hub

The site, known as Neumark-Nord 2 in central Germany, yielded a dense concentration of fragmented animal remains alongside Neanderthal-made stone tools. Archaeologists meticulously excavated and analyzed the bones of at least 172 large mammals, including horses, deer, and bovids like ancient cattle. Tens of thousands of bone fragments were recovered from a relatively small area, suggesting intensive activity focused specifically on this location. The sheer volume and condition of the bones provided crucial clues about the behaviors that occurred there.

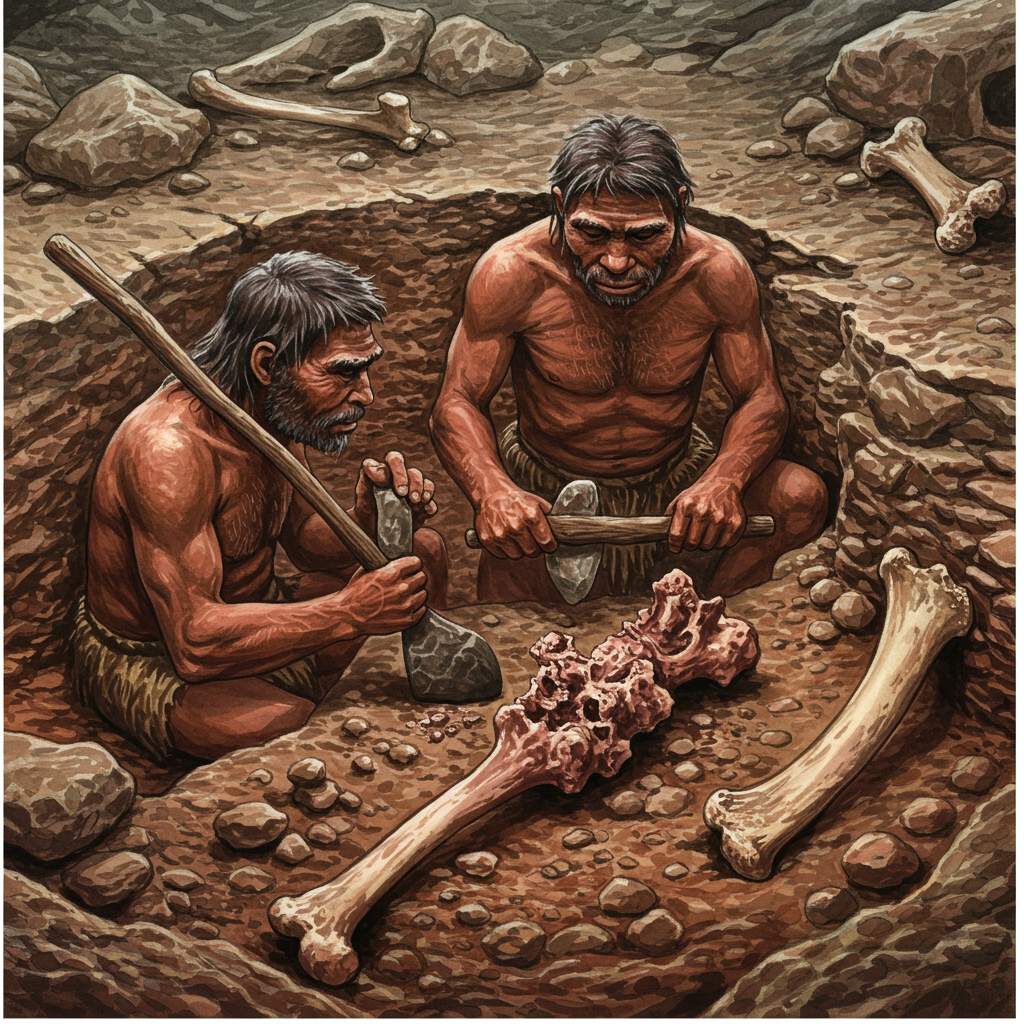

Researchers noted tell-tale signs of deliberate processing. The bones had been systematically broken open using hammerstones, likely to access nutrient-rich marrow within the cavities. But the processing didn’t stop there. The bones were further crushed and chopped into smaller pieces. This extreme fragmentation indicates a clear purpose beyond just accessing marrow for immediate consumption.

The Ingenious Process: Smashing, Chopping, and Heating

The detailed analysis of the bone fragments painted a picture of a precise, multi-step process. First, large bones were smashed open. This gave access to the marrow, a valuable food source. However, to extract the maximum amount of fat (or grease), especially from the spongy bone tissue, Neanderthals needed another step.

The small, crushed fragments found at Neumark-Nord show signs consistent with heating. While direct evidence of pottery or other vessels used for boiling is absent (the earliest known pottery is much younger), experimental archaeology shows that materials like animal skins or birch bark could have served as containers for heating water over a fire. The researchers propose that Neanderthals collected the bone fragments, perhaps accumulating them over time, and then brought them to this site. Here, they likely heated the crushed bones in water, allowing the fat to render out and rise to the surface, where it could be skimmed off. This was a labor-intensive and time-consuming endeavor, requiring significant effort to process such a large quantity of bones.

Why Fat Was Life-Saving for Neanderthals

For hunter-gatherers like Neanderthals, securing enough calories was a constant challenge. While meat provided protein, consuming too much protein without sufficient fat or carbohydrates can lead to a dangerous condition known as protein poisoning or “rabbit starvation.” Given their heavily meat-based diet, Neanderthals would have been particularly vulnerable to this.

Fat is incredibly calorie-dense, offering more than twice the energy per gram compared to protein or carbs. Accessing bone grease provided a vital source of concentrated calories that could supplement their diet, especially during lean times or when hunting yielded primarily lean muscle meat. The systematic extraction of bone fat was likely a critical survival strategy, helping them balance their nutritional intake and avoid protein poisoning. As archaeologist Osbjorn Pearson noted, this behavior demonstrates surprising creativity and innovation.

Pushing Back the Timeline for Sophisticated Resource Management

The discovery at Neumark-Nord significantly alters the timeline for “resource intensification” – the practice by hominins of maximizing the utility of available resources through complex processing. Previous archaeological evidence for intensive bone processing, primarily attributed to early Homo sapiens, dated back only to around 28,000 years ago. Finding a clear example of this sophisticated, labor-intensive technique practiced by Neanderthals 125,000 years ago represents a massive leap backward in the archaeological record.

This finding challenges earlier perceptions of Neanderthals as less capable or more primitive than modern humans. Study co-author Wil Roebroeks suggests this complex behavior implies Neanderthals might have been “more similar to historically documented foragers” than previously thought, capable of foresight, strategic planning, and potentially even food storage. The accumulation of large quantities of bones for processing suggests a capacity for delayed gratification and future-oriented behavior. This aligns with other evidence of Neanderthal ingenuity, such as their production of birch bark pitch adhesive, which required sophisticated temperature control hundreds of thousands of years ago.

A Glimpse into Neanderthal Culture and Survival

The Neumark-Nord site is part of a larger landscape complex that provides an unprecedented look at various Neanderthal activities in the same region during this period. Different areas show evidence of distinct tasks, from specific hunting and limited butchery sites to areas dedicated to processing massive animals like straight-tusked elephants and, crucially, the fat rendering site at Neumark-Nord 2. This suggests a strategic use of the landscape, with specific locations chosen or designated for different purposes.

Study first author Lutz Kindler emphasizes that the archaeological science of studying hominins aims to find similarities between past and present human behavior. This discovery of organized, intensive fat extraction highlights such a parallel, demonstrating a deep understanding of nutrition and resource optimization shared across the Homo genus. Understanding how Neanderthals adapted their diet and utilized resources offers valuable insights into the broader story of human evolution and the adaptations that contributed to our ancestors’ survival and success. The ability to extract maximum nutrition, especially calories from fat, would have significantly bolstered their chances of survival and reproductive success in challenging environments.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did Neanderthals extract fat from animal bones 125,000 years ago?

At the Neumark-Nord site in Germany, Neanderthals used a multi-step process. First, they smashed large animal bones using stone tools like hammerstones to access the inner marrow. Then, they further crushed and chopped these bones into thousands of small fragments. These fragments were likely heated in water (possibly in perishable containers), allowing the fat to render out and be collected. This systematic, labor-intensive method maximized the nutritional yield from animal carcasses.

Where was this ancient Neanderthal ‘fat factory’ located, and why is the site important?

The “fat factory” was located at the Neumark-Nord 2 site in central Germany, dating back approximately 125,000 years. The site is important because its excellent preservation allowed archaeologists to find a dense concentration of processed bones and tools. It represents the earliest clear evidence of large-scale, intensive bone grease rendering by Neanderthals, pushing back the known timeline for this sophisticated resource management technique by about 100,000 years and providing crucial insights into their capabilities and planning.

Why was bone fat extraction crucial for Neanderthal survival and diet?

Bone fat was vital because it provided a high-calorie energy source, offering more than double the calories per gram compared to protein. For Neanderthals who relied heavily on meat, extracting this fat helped them obtain sufficient calories and, critically, prevented protein poisoning (rabbit starvation), a potentially lethal condition resulting from consuming too much lean protein without enough fat or carbohydrates. This practice significantly boosted their ability to survive and thrive.

Conclusion

The discovery of the 125,000-year-old “fat factory” at Neumark-Nord offers compelling proof of Neanderthals’ complex cognitive abilities and advanced survival strategies. Far from being simple, immediate-return foragers, these ancient hominins demonstrated sophisticated planning, resource intensification, and a deep understanding of nutrition. Their ability to systematically process animal bones for fat highlights an ingenious adaptation that was likely crucial for their survival in challenging environments. This finding not only rewrites a key chapter in the history of Paleolithic resource management but also reinforces the growing evidence that Neanderthals were remarkably capable and adaptable, sharing many behavioral complexities with modern humans.