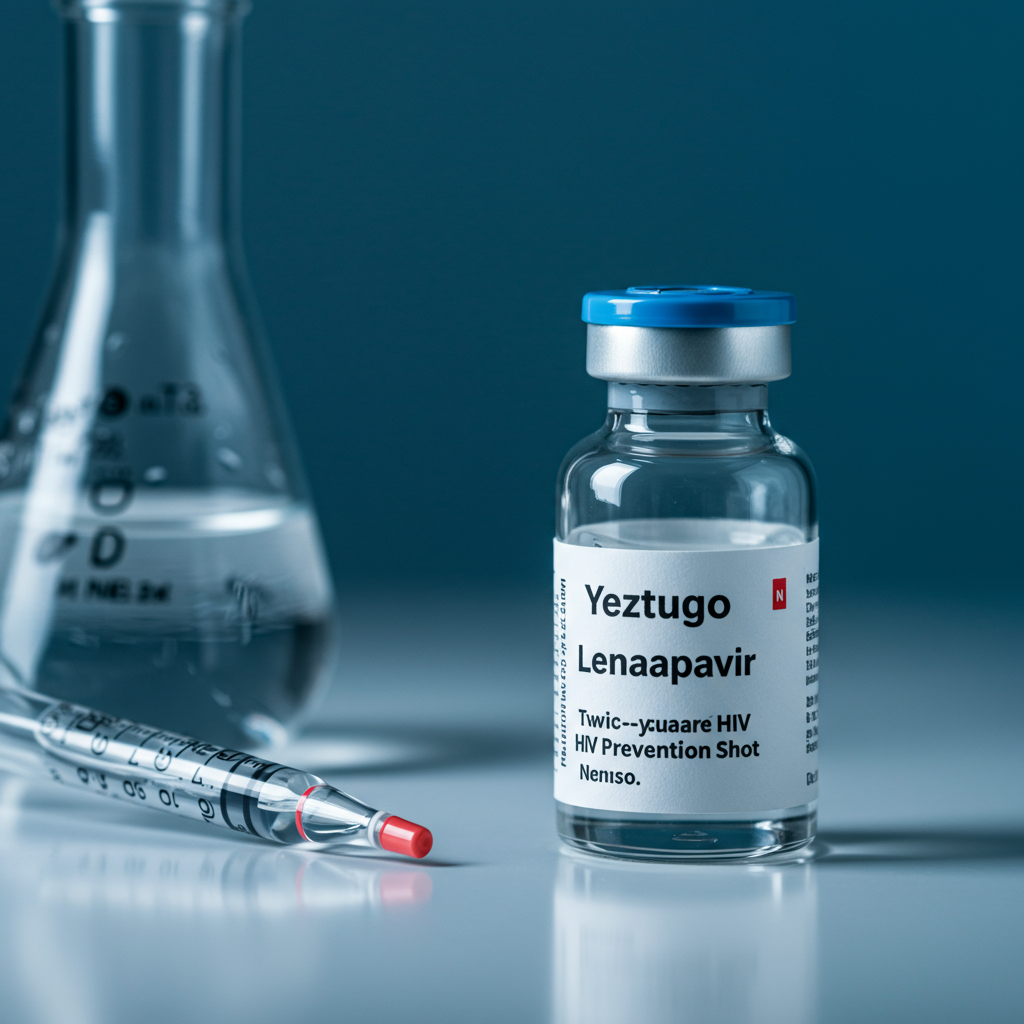

A new era in HIV prevention has begun with the U.S. approval of the world’s first and only twice-a-year injectable shot to prevent HIV. Developed by Gilead Sciences and known scientifically as lenacapavir, the drug will be marketed for prevention under the brand name Yeztugo. This landmark approval represents a significant stride in the global fight against HIV, offering a potent new tool that could protect millions. However, experts caution that the shot’s full potential hinges on overcoming substantial barriers to access and affordability worldwide.

A Game-Changer in HIV Prevention

For decades, daily oral pills (known as PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis) have been a cornerstone of HIV prevention for individuals at high risk. While effective, daily pills can be challenging for some to remember consistently or may carry stigma. Other injectable options exist but require visits every two months. Lenacapavir stands out because it needs to be administered only twice a year via subcutaneous injections, typically in the abdomen, creating a small “depot” of medication that slowly releases over six months.

This long-lasting duration is seen as potentially transformative. Experts like Greg Millett of amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, believe this shot “really has the possibility of ending HIV transmission.” Kevin Robert Frost, amfAR’s CEO, noted that requiring shots only twice annually should dramatically improve long-term adherence compared to daily pills, making it an “indispensable tool for ending the HIV epidemic.” Carlos del Rio, a distinguished professor at Emory University, echoed this, calling Yeztugo the “transformative PrEP option we’ve been waiting for” due to its ability to address key barriers like adherence and stigma.

Powerful Clinical Evidence

Clinical trials have demonstrated the remarkable efficacy of lenacapavir. In a rigorous study conducted in South Africa and Uganda involving over 5,300 sexually active young women and teenage girls, there were zero HIV infections reported among those receiving the twice-yearly shot. This compared favorably to an approximately 2% infection rate in the group taking daily pills.

A separate study involving gay men and gender-nonconforming individuals in the U.S. and several other countries also showed the twice-yearly shot to be nearly as effective, significantly reducing new infections. Participants like Ian Haddock, who struggled with daily pill adherence, found the twice-yearly shot much easier to manage. “Now I forget that I’m on PrEP because I don’t have to carry around a pill bottle,” said Haddock, highlighting how the simplified schedule broadens the opportunity for prevention across diverse populations.

The shot works by inhibiting the HIV virus’s capsid, disrupting its life cycle. It’s crucial that individuals test negative for HIV before starting Yeztugo, as it prevents infection but does not treat existing HIV or protect against other sexually transmitted infections. Some users have reported injection-site pain, which researchers suggest can be eased with cold packs.

The Major Hurdles: Access and Affordability

Despite its scientific promise, the widespread impact of Yeztugo faces significant challenges related to access and cost. Global efforts to end the HIV pandemic by 2030 have stalled, with hundreds of thousands of new infections occurring annually worldwide. Only a fraction of those in the U.S. who could benefit from PrEP are currently using it. A study in The Lancet HIV found that U.S. states with greater access to oral PrEP saw a decrease in new HIV cases, while states with low access experienced an increase, starkly illustrating the link between availability and prevention rates.

The U.S. list price for a year’s supply of Yeztugo is $28,218. While Gilead states this is comparable to some other PrEP options and anticipates insurance coverage and financial assistance programs, experts are concerned. Michael Weinstein, President of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF), raised alarms about the high cost.

Domestically, access could be hampered by ongoing upheaval in the U.S. healthcare system, including proposed cuts to public health agencies and Medicaid. Carl Schmid of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute worries these cuts could dismantle HIV prevention outreach and testing programs, preventing vulnerable populations from even learning about or qualifying for the shot. Furthermore, the Supreme Court is considering a case that could potentially overturn requirements for insurers to cover PrEP without co-pays, adding another layer of uncertainty.

Global Distribution and Equity Concerns

Globally, the picture is complex. Gilead has applied for approval in other countries and has made agreements with six generic drug manufacturers to produce lower-cost versions for 120 low-income countries, primarily in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean. The company plans to supply doses for up to 2 million people in these regions at no profit until the generics are available.

However, critics argue this doesn’t go far enough. Winnie Byanyima, Executive Director of UNAIDS, stated that if the price remains unaffordable, the drug “will change nothing” in terms of impacting the epidemic globally. A significant concern is the exclusion of middle-income countries, such as those in Latin America, from these low-cost generic agreements, leaving many at-risk populations without access. Dr. Gordon Crofoot, a lead researcher, stressed that access to highly effective PrEP like lenacapavir is needed for “everyone in every country who’s at risk of HIV.”

While the approval of the twice-yearly HIV prevention shot marks a monumental scientific achievement offering unprecedented convenience and efficacy, its true impact on ending the HIV epidemic worldwide will ultimately depend on overcoming the significant and persistent challenges of equitable access and affordability.