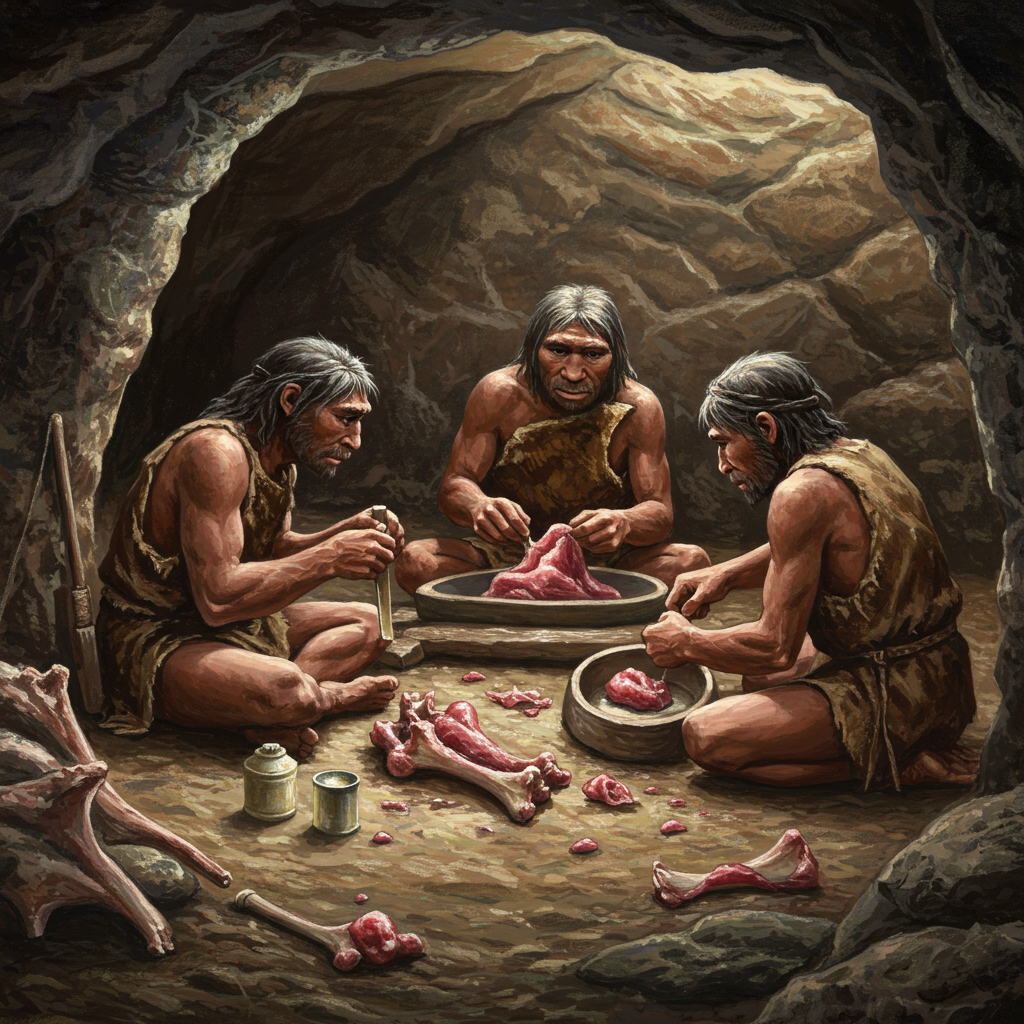

For decades, the narrative surrounding neanderthals often painted them as less sophisticated than their Homo sapiens cousins. However, groundbreaking archaeological discoveries continue to challenge this view, revealing complex behaviors and advanced resource strategies. A remarkable find in Germany is now significantly pushing back the timeline for a critical survival technique: the intensive extraction of bone fat, or grease rendering. This sophisticated practice, previously thought to be a hallmark of much later human groups, was being expertly performed by Neanderthals a staggering 125,000 years ago.

This discovery reveals Neanderthals possessed ingenuity and foresight previously underestimated. It demonstrates a deep understanding of nutritional value and the implementation of complex, multi-step processes to maximize food resources. Identifying such early evidence of resource intensification fundamentally reshapes our understanding of Neanderthal capabilities and their place in the story of human evolution.

The Revolutionary Discovery at Neumark-Nord

The compelling evidence for this ancient practice comes from the remarkable Interglacial Paleolithic site of Neumark-Nord (specifically location NN2/2B) in present-day Germany. Excavations conducted between 2004 and 2009 unearthed a treasure trove of artifacts and faunal remains. The site, situated near the margin of a shallow prehistoric pool, appears to have been a central hub for a specific activity: bone processing on a massive scale.

Researchers analyzed remains from at least 172 large mammals found concentrated within a roughly 50-square-meter area. The animals included horses, deer, and bovids, indicating a diverse range of prey was brought to this location. Mixed among the dense bone material were more than 16,500 flint artifacts, stone manuports, and clear signs of fire use.

Evidence from the “Bone Floor”

The sheer density of bones at the Neumark-Nord 2/2B site led researchers to describe the accumulation as a “bone floor.” All bones larger than 3 cm were meticulously recorded during the excavation, creating a striking visual representation of the activity concentrated in this single area. Many bones were discovered within rounded depressions at the base of the archaeological layer, indicating how the material settled over time after the processing occurred.

Crucially, the condition of the bones provided the strongest clues about Neanderthal activities. The vast majority of the bones from these large mammals had been systematically fragmented. This wasn’t the random breakage seen from animal scavenging; it was deliberate and extensive, clearly anthropogenic. This level of fragmentation, reducing large limb bones into tens of thousands of tiny pieces, would have required significant effort.

Dating the Site and Setting

The Neumark-Nord site complex dates back approximately 125,000 years. This places the activities squarely within the Last Interglacial period, a time when climates were relatively warm, similar to or even warmer than today. The specific location at NN2/2B, beside a shallow body of water, would have provided a ready source of liquid needed for the processing technique the Neanderthals employed.

The date is critical because previous definitive evidence for intensive bone grease rendering by hominins only dated back to around 28,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic. At that much later time, modern humans were the predominant hominin species in Europe. The Neumark-Nord discovery pushes this timeline back by nearly 100,000 years, placing the practice firmly within the Neanderthal era.

Decoding the Ancient Process

Analyzing the thousands of bone fragments revealed a sophisticated, multi-stage process. It wasn’t simply about breaking bones to get at the calorie-rich marrow contained within the hollow cavities, although that was likely a first step. The Neanderthals went much further, targeting the lipids stored within the dense, spongy tissue of the bones.

Evidence suggests imported bones were first smashed open, likely using hammerstones, to extract marrow. This is indicated by hammerstone impact marks observed on bones like an aurochs humerus found at the site. But the processing didn’t stop there.

From Carcass to Calories: Step-by-Step

Following marrow extraction, the bones were then systematically crushed and chopped into much smaller fragments. This extensive fragmentation was specifically aimed at increasing the surface area of the bone material. This increased surface area is essential for the next crucial step: extracting fat from both the spongy (cancellous) and compact (cortical) bone tissues, which retain significant amounts of grease even after marrow is removed.

Among the tens of thousands of fragmented bones, approximately 2,000 tiny pieces showed clear signs of having been exposed to fire after being broken. This exposure resulted in characteristic color changes, ranging from dark brown and black to white, and altered textures commonly found in heated bones. Researchers interpret these findings as evidence of heating the crushed bones in water to render out the fat.

The Technology Behind the Technique

The presence of heated bones, along with heated flint artifacts and stones at the site, confirms that fire played a crucial role in the process. While the analysis didn’t find direct evidence of boiling vessels, the researchers propose a plausible method. Given that pottery wasn’t invented until much later (around 20,000 years ago), Neanderthals would have needed alternative containers capable of holding water over a fire.

Based on recent experiments, perishable materials like sturdy animal skins (such as deer hide) or sheets of birch bark could be fashioned into containers. These vessels could then be suspended or carefully placed near or directly on a fire to heat the water and bones, effectively boiling them to release the grease. This highlights remarkable innovation and adaptability, utilizing available natural materials to create essential processing tools. The systematic application of this method at Neumark-Nord indicates a deliberate technological strategy for food processing.

Why Bone Fat Mattered

Why would Neanderthals invest such substantial time and effort into processing bones beyond simply cracking them for marrow? The answer lies in the incredible nutritional value of fat. For hunter-gatherers, fat is a critical resource, providing more than double the calories per gram compared to protein or carbohydrates. In environments where food sources might fluctuate, securing ample fat is vital for survival.

Accessing the fat within bones, especially from large mammals, taps into a highly concentrated energy source. This wasn’t just about getting “extra” calories; it was about accessing precious lipids that offered a significant caloric boost and were less perishable than lean meat.

Nutritional Powerhouse

Neanderthals were primarily meat-eaters, and while meat provides essential protein, an exclusive diet of lean protein can be dangerous, leading to a condition known as “rabbit starvation” or protein poisoning. This occurs when the body receives insufficient fat or carbohydrates relative to protein, overwhelming the liver’s ability to process excess amino acids.

By systematically extracting and consuming bone grease, Neanderthals could balance their high-protein meat diet with crucial fats. This strategic dietary management would have provided stable energy, improved health, and supported the high metabolic demands of their active lives. The practice demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of nutritional needs and how to meet them using available resources.

Beyond Survival: Planning and Storage

The sheer scale of the processing activity at Neumark-Nord 2/2B suggests more than just immediate consumption. Processing the bones of over 170 large animals is a substantial undertaking, indicative of strategic planning. Rendered animal fat, unlike fresh meat, can be stored and transported, serving as a preserved energy source.

This suggests the Neanderthals at Neumark-Nord may have been producing bone grease not only for immediate dietary needs but also potentially for later use, perhaps during leaner times or for use during travel. Such foresight and the ability to plan for future resource needs are hallmarks of complex cognitive behavior, adding another layer to the growing evidence of Neanderthal sophistication.

Reshaping Our View of Neanderthals

For a long time, Neanderthals were often depicted as brutish, less capable ancestors compared to modern humans. Discoveries like the “fat factory” at Neumark-Nord actively dismantle these outdated stereotypes. This finding reveals a level of ingenuity, planning, and resource management that rivals, and in some cases predates, similar practices attributed to early Homo sapiens.

The identification of intensive grease rendering at 125,000 years ago significantly pushes back the known timeline for such resource intensification practices within the Homo genus. Previously, the earliest clear cases were associated with Upper Paleolithic sites much later. This demonstrates that Neanderthals were innovators capable of developing complex technological solutions to meet their survival needs, well before modern humans are traditionally credited with such sophistication.

Challenging the “Primitive” Narrative

The systematic process of smashing, crushing, and boiling bones using improvised containers requires not only physical effort but also significant knowledge and planning. It indicates an understanding of material properties (how fat is stored in bone), physics (how heat transfers and affects lipids), and engineering (creating functional vessels). This complex sequence of actions is a strong indicator of advanced cognitive abilities and cultural transmission of knowledge within Neanderthal groups.

Experts note the striking similarity between this ancient bone processing and resource utilization behaviors documented among historically recorded human foragers. This suggests that Neanderthals’ adaptations and survival strategies may have been far more akin to later modern humans than previously thought, underscoring their adaptability and behavioral flexibility.

Complex Landscape Use

The Neumark-Nord 2/2B “fat factory” wasn’t an isolated activity. It was part of a broader, strategic use of the landscape during the Last Interglacial period. Research across the Neumark-Nord complex reveals task-specific locations. For instance, nearby sites show evidence of hunting and intensive butchery of massive straight-tusked elephants and more minimal processing of deer elsewhere.

This suggests Neanderthals were not simply opportunistic inhabitants but active managers of their environment, choosing specific locations within the landscape for particular activities – a dedicated site for bone grease rendering, other sites for initial butchery of large kills, and potentially others for different tasks. This integrated view of their activities demonstrates a level of planning and ecological engagement previously underestimated. The scale of their impact on herbivore populations across this landscape, documented through numerous sites, hints at a robust, organized subsistence strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is bone grease rendering and why did Neanderthals do it?

Bone grease rendering is the process of extracting calorie-rich fat (lipids) from animal bones by breaking them down and heating them, typically in water. Neanderthals performed this process as early as 125,000 years ago in Germany. They did this primarily to access a dense energy source to supplement their high-protein diet, helping them obtain vital calories and potentially avoid nutritional issues like protein poisoning. The rendered fat also offered a form of food storage.

Where was this ancient Neanderthal bone processing site located?

The site where this early evidence of intensive bone grease rendering was found is called Neumark-Nord (specifically location NN2/2B). It is located in what is now central Germany. The site dates back approximately 125,000 years and was situated near the margin of a shallow prehistoric pool during the Last Interglacial period.

How does this finding change our understanding of Neanderthal capabilities?

This discovery dramatically changes our understanding of Neanderthal sophistication. It pushes back the timeline for complex resource intensification by tens of thousands of years, demonstrating that Neanderthals were capable of intricate planning, multi-step technological processes, and sophisticated dietary strategies much earlier than previously believed. It shows they were innovative problem-solvers who understood the nutritional value of fat and devised methods to extract it on a significant scale.

The discovery at Neumark-Nord provides compelling new insights into the lives of Neanderthals. It paints a picture of a species capable of complex thought, strategic planning, and innovative technology, utilizing their environment and resources in sophisticated ways. The “fat factory” stands as a powerful testament to their ingenuity, challenging old stereotypes and solidifying their place as a highly adaptable and capable branch of the human family tree. This finding underscores the ongoing evolution of our understanding of prehistoric hominins and highlights the value of dedicated archaeological research in revealing the complexities of our ancient relatives.

Word Count Check: 1127