A massive explosion rocked the remote Siberian sky over a century ago. On June 30, 1908, a fiery object tore through the atmosphere. This immense blast, known as the <a href="https://news.quantosei.com/2025/07/01/in-honor-of-world-asteroid-day-a-short-history-of-planetary-defense/” title=”Essential Guide to Planetary Defense & Asteroid Science”>tunguska event, flattened vast stretches of forest. It remains the largest cosmic-impact event in recorded history.

The incident devastated over 830 square miles (more than 2,000 square kilometers) of frozen taiga. It left behind a lasting scientific puzzle. The Tunguska event serves as a powerful reminder. Space objects intersecting Earth’s path pose potential dangers.

June 30 is now recognized globally. It’s International Asteroid Day. This day raises awareness about asteroid hazards. It promotes global efforts to address these rare but potentially deadly threats.

The Day the Sky Split Open

Eyewitness accounts from 1908 are haunting. Many people reported seeing a blazing fireball. It streaked across the sky at immense speed. Estimates suggest it traveled around 60,000 miles per hour.

Witnesses in Kirensk described the sight. They saw a ball of fire descend toward the horizon. This was followed by deafening noises. One person heard “separate deafening crash[es] like peals of thunder.” Then came “eight loud bangs like gunshots.”

Another observer said the object “took on a flattened shape” as it neared the ground. Some called it a “flying star with a fiery tail.” It seemed to vanish into the air.

One chilling report states: “I saw the sky in the north open to the ground and fire poured out.” The fire was “brighter than the sun.” People were terrified. “The sky closed again and immediately afterward, bangs like gunshots were heard.” They thought stones were falling.

A witness was standing on a porch at a trading post. A powerful heat wave struck him. He was reportedly thrown twenty feet. “The sky was split in two,” his account reads. “High above the forest the whole northern part of the sky appeared covered with fire.” He felt “a great heat, as if my shirt had caught fire.” Then came a “mighty crash.” The earth trembled. A “hot wind, as if from a cannon,” blew past the huts. The blast damaged buildings. Window panes were blown out. An iron hasp on a barn door broke. These accounts paint a vivid picture of the cosmic intrusion.

An Unsolved Scientific Puzzle

Seismic instruments detected the explosion. They were over 600 miles away. Yet, scientific expeditions faced delays. The first major investigation didn’t reach the remote site until almost two decades later. Mineralogist Leonid Kulik led early Soviet expeditions in the 1920s and 1930s. His team documented the aftermath.

The effects were clear upon arrival. Trees were flattened radially outward from a central point. This damage spanned hundreds of miles. Trees directly beneath the assumed blast site remained standing. However, they were stripped completely bare of branches and bark.

Crucially, researchers found no impact crater. This is the core mystery of Tunguska. Scientists estimate the object was between 50 and 100 meters (150 to 300 feet) across. It likely disintegrated in the atmosphere. This created a massive “airburst.” The explosion occurred at an altitude of roughly 6 to 10 kilometers (4 to 6 miles).

The energy released was immense. Estimates suggest it equaled a 12-megaton bomb. This is comparable to modern nuclear weapons. It was enough energy to level a large modern city. The absence of a crater strongly supports the airburst hypothesis. The object vaporized before hitting the ground.

Evidence and Ongoing Debate

Scientists have mapped the blast zone over time. It has a distinctive butterfly shape. Research since the 1990s provides more clues. Studies of local tree resin revealed trapped particles. These particles contain elements like nickel and iridium. These elements are more common in meteorites than in Earth’s crust. This provides geochemical evidence of an extraterrestrial origin.

Additional evidence supports the airburst theory. Researchers found rock fragments and shocked quartz. Irregularities in tree rings also point to a powerful atmospheric blast. The prevailing scientific consensus favors an asteroid airburst. However, some scientists have proposed a comet was responsible.

A notable debate concerns nearby Lake Cheko. Some researchers suggest it could be a crater formed by a fragment. Other studies dispute this hypothesis. No confirmed evidence of craters or the original object has ever been definitively found at Tunguska. Despite advanced simulations and analysis, the exact nature of the Tunguska object remains a subject of scientific inquiry.

New Perspective from Space

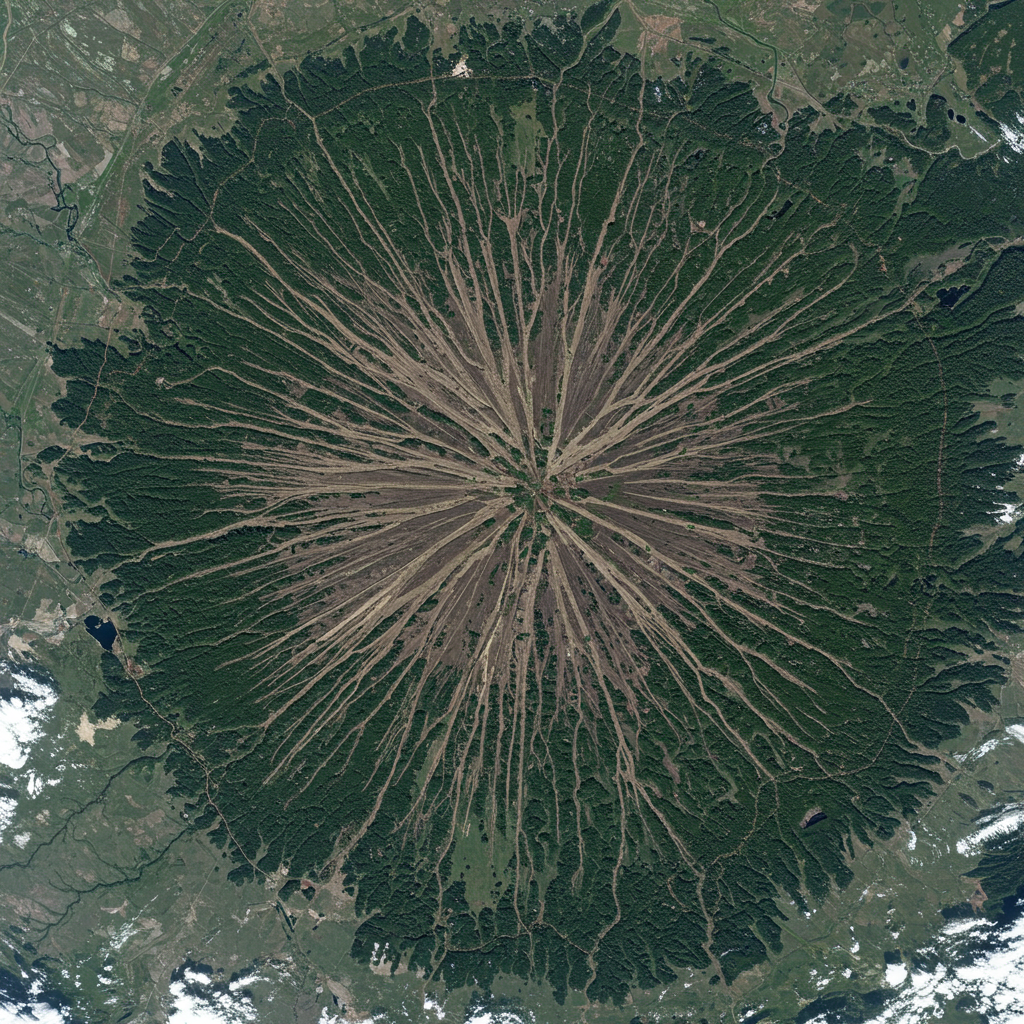

More than a century after the event, nature has healed the landscape. Recent satellite imagery offers a view of the site today. NASA’s Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured images. One such image was taken on July 6, 2024. It shows the present-day appearance of the blast zone.

The imagery reveals healthy pine forests, marshes, and rivers. There are no direct visible signs of an impact crater. There’s no obvious damage from the massive blast visible from orbit today. The image helps illustrate the approximate epicenter. Field surveys determined this location. While the scar has faded, the event’s scale remains a stark reminder.

Tracking Threats: The World of Near-Earth Objects

The Tunguska event highlights the risks from space. It drives modern efforts to track Near-Earth Objects (NEOs). NASA’s Earth Observatory defines NEOs. They are comets or asteroids. Their orbits bring them within 1.3 astronomical units of the Sun.

NASA actively monitors these objects. As of June 2025, NASA’s catalog listed over 38,000 known near-Earth asteroids. This number is growing rapidly. Asteroid surveys add hundreds of new entries monthly.

Observatories contribute significantly to this count. In just a few days in June 2025, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory reported a discovery. They found 2,104 new asteroids. Seven of these were classified as NEOs. Astronomers expect this observatory to reveal millions more. It will scan vast portions of the night sky.

Fortunately, most NEOs pose no threat. They are unlikely to intersect Earth’s orbit. However, the potential for a rare, large impact remains. This possibility spurred enhanced planetary defense efforts.

Planetary Defense: Learning from History

The risk of a “city-killer” asteroid impact led to action. In 2016, NASA established the Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO). Its mission is clear: find and track objects that could be hazardous. This office oversees initiatives like the NEO Observations Program.

A more recent event underscored the danger. In 2013, a meteor exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia. This event was recorded by modern instruments. That airburst was powerful. Estimates suggest it was up to 33 times stronger than the Hiroshima atomic bomb. The Chelyabinsk event reignited global concern about asteroid threats.

In the wake of Chelyabinsk, international cooperation increased. Space agencies worldwide united. They work to mitigate asteroid threats. The UN’s Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) supports key initiatives. These include the International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN). They also back the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group (SMPAG). Both groups boost international cooperation. They aim to improve detection and response to NEO threats. International Asteroid Day is part of these efforts. It emphasizes public awareness and coordinated crisis communication.

Modern technology improves detection capabilities. Missions like the planned NEO Surveyor will enhance tracking. The successful DART mission in 2022 demonstrated a mitigation technique. It proved a kinetic impactor could change an asteroid’s path. Events like Tunguska and Chelyabinsk are reminders. They highlight the dangerous potential of asteroid impacts. They underscore the need for constant vigilance. Space holds many unpredictable dangers.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the Tunguska event and why is it famous?

The Tunguska event was a massive explosion. It happened over Eastern Siberia on June 30, 1908. It’s the largest known asteroid-related blast in history. It flattened over 830 square miles of forest. It’s famous because despite its immense power, it left no impact crater. Scientists believe it was caused by a meteoroid or comet exploding in the atmosphere. This mystery, the lack of a crater, and the remote location captured public imagination and spurred scientific investigation.

How do scientists track potential asteroid threats today?

Scientists track potential asteroid threats by identifying and monitoring Near-Earth Objects (NEOs). These are space objects whose orbits come close to the Sun (and potentially Earth). NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO) leads this effort in the US. They use ground-based telescopes like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and plan future space missions like NEO Surveyor to find and track these objects. International efforts, such as the UN-supported IAWN and SMPAG, facilitate global cooperation in detection and response planning.

Could an event like Tunguska happen again, and what are the defenses?

Yes, an event like Tunguska could potentially happen again, as Earth’s orbit intersects with many space objects. While large impacts are rare, the risk exists. The Tunguska and Chelyabinsk events underscore this. Global defenses involve continuous detection and tracking of potentially hazardous NEOs by organizations like NASA’s PDCO. International cooperation through networks like IAWN is vital for early warning. Scientists are also developing and testing mitigation techniques, such as using kinetic impactors (like the DART mission demonstration) to alter an object’s trajectory, offering potential defense options.

The Tunguska event remains a compelling enigma. The lack of a crater still fuels scientific debate. Yet, its core lesson is undeniable. Earth is vulnerable to cosmic encounters. Over a century later, the site shows nature’s resilience in satellite images. But the event’s legacy persists. It drives modern efforts in planetary defense. Tracking near-Earth objects and improving detection technology is vital. Continued international cooperation is essential. Vigilance against space’s unpredictable dangers is our best defense.

Word Count Check: 1155