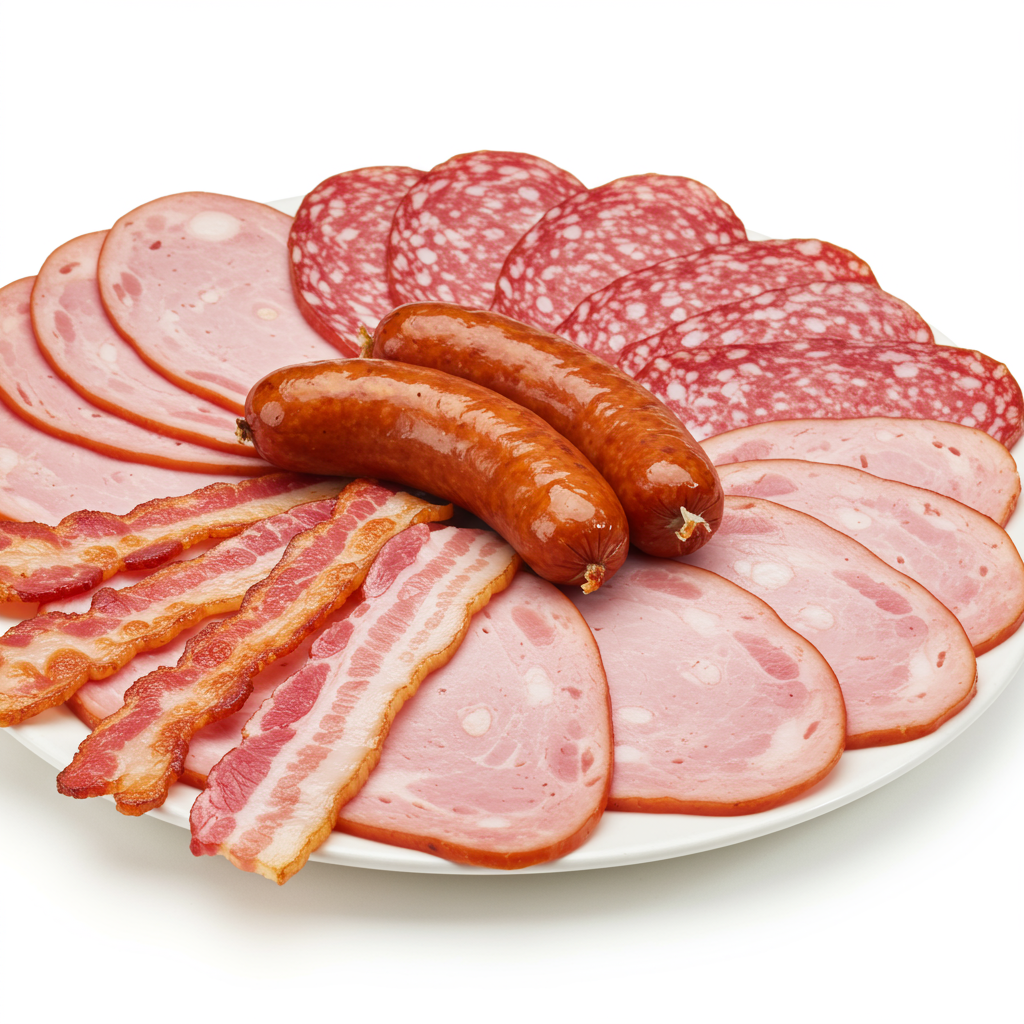

Is there a “safe” amount of processed meat you can eat without increasing your risk of serious health issues? According to recent, extensive research, the answer appears to be no. Even small amounts of foods like bacon, sausage, and deli meats may elevate your vulnerability to diseases like type 2 diabetes and certain cancers.

This finding comes from a massive review of over 70 previous studies, collectively involving millions of participants. US researchers meticulously analyzed the complex relationships between consuming ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and three significant health problems: type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and colorectal cancer. While they examined sugar-sweetened beverages and trans fatty acids, processed meat consistently showed the strongest negative associations.

Understanding the Startling Findings

The core message from the University of Washington team behind the review is stark: increased consumption of processed meat correlates directly with higher health risks. This pattern suggests there isn’t a threshold below which consumption is completely risk-free for conditions like diabetes and colorectal cancer. The researchers noted a “monotonic increase,” meaning the risk goes up incrementally with every additional amount consumed, no matter how small.

For illustration, the study pointed to specific examples. Eating just the equivalent of one hot dog per day was associated with significant risk increases compared to eating no processed meat. This daily habit was linked to at least an 11 percent greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes. It was also associated with at least a 7 percent higher risk of colorectal cancer. These are compelling figures highlighting the potential impact of even seemingly small dietary choices over time.

Putting the Research in Context

While the associations identified in this specific review were described as relatively weak and do not prove direct cause and effect (as is common with observational studies), the sheer scale of the data analyzed adds considerable weight to the findings. The studies reviewed often rely on self-reported dietary information, which can sometimes be inaccurate. However, the research employed a rigorous “Burden of Proof” methodology. This method is designed to be more conservative in assessing health impacts, meaning the reported risk values are likely minimums and could even underestimate the true danger.

This research aligns with a growing body of evidence linking ultra-processed foods (UPFs) more broadly to a wide array of adverse health outcomes. An extensive umbrella review published in The BMJ in 2024 synthesized evidence from 14 meta-analyses involving nearly 10 million participants. This review found “convincing” or “highly suggestive” evidence connecting greater UPF exposure to higher risks across multiple domains.

The Broader Problem with Ultra-Processed Foods

Processed meat is a prime example of an ultra-processed food. The BMJ review on UPFs linked them definitively to increased risks of:

Early death (from any cause and specifically cardiovascular disease)

Cardiometabolic diseases (including type 2 diabetes and obesity)

Mental health issues (such as anxiety and depression)

Other problems (like poor sleep and wheezing)

These findings reinforce the concerns raised by the processed meat review, positioning these products within a larger category of foods strongly associated with poor health. The potential mechanisms are multi-faceted. UPFs often have poor nutritional profiles – high in unhealthy fats, sugar, and salt, while being low in fiber and essential micronutrients. They can displace more nutritious whole foods in the diet. Furthermore, components like additives, contaminants from packaging, and alterations to the food matrix during processing may negatively impact digestion, nutrient absorption, gut health, and inflammatory responses in the body.

The ‘Protein Package’: Source Matters Most

Understanding the health impacts of food isn’t just about single ingredients; it’s about the entire “package.” When it comes to protein, its effect on health depends heavily on the other nutrients and compounds it comes with. Sources like fatty cuts of red meat or processed meats often come bundled with unhealthy saturated fat and sodium. Many processed meats also contain nitrates or nitrites, which can form carcinogenic compounds when digested.

Leading health institutions like the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health emphasize this point. Their research consistently links regular consumption of red meat, and especially processed red meat, to increased risks of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), part of the World Health Organization (WHO), classifies processed meat as “carcinogenic to humans” based on sufficient evidence linking it to colorectal cancer, and red meat as “probably carcinogenic.”

Replacing these sources with healthier protein options is associated with significantly reduced health risks. This includes plant-based proteins like beans, lentils, nuts, and seeds, which offer fiber, beneficial fats, and no cholesterol. Healthier animal protein options like fish (especially fatty fish rich in omega-3s) and poultry are also preferable alternatives.

Navigating Conflicting Information

While the scientific consensus points towards minimizing or eliminating processed meat, you might encounter differing perspectives. For instance, a controversial review published in the Annals of Internal Medicine suggested that for people eating average amounts (around 3-4 times per week), the link to major diseases wasn’t statistically “important” according to their specific criteria. This led that particular panel to suggest most people could continue their current intake.

However, it’s crucial to understand the context and expert commentary surrounding that review. Even experts quoted in that same article highlighted significant caveats:

Processed meat specifically remains problematic due to its high sodium and saturated fat content, strongly linked to heart disease.

The review primarily looked at “average” consumption and did not suggest higher quantities were safe.

Cooking methods (like high-temperature grilling or frying) create carcinogens in meat, regardless of processing.

And importantly, even that review’s findings didn’t suggest red or processed meat was healthy. Experts continued to recommend a diet centered on nutrient-dense, plant-based foods as being superior for overall health.

Therefore, while one review might debate the magnitude of risk at average levels based on specific evidence criteria, the overwhelming body of research, including the large review finding no “safe” level and the comprehensive UPF review, strongly supports the recommendation to limit or avoid processed meat consumption for optimal health.

Towards Healthier Dietary Choices

The findings from these reviews underscore the need for public health action and informed individual choices. The researchers in the Nature Medicine study suggested their data provides critical information for policymakers tasked with developing dietary guidelines and initiatives to reduce processed food consumption. This aligns with recommendations from other bodies supporting measures like warning labels or taxes on unhealthy foods.

Making significant dietary changes can be challenging, especially in environments where processed foods are highly accessible and convenient. However, for individuals, the message remains clear: prioritize whole, unprocessed foods as much as possible. This means focusing on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, and lean protein sources. Reducing or eliminating processed meat from your diet is a concrete step supported by robust evidence to lower your risk of serious chronic diseases.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is processed meat and why is it considered unhealthy?

Processed meat refers to meat that has been transformed through salting, curing, fermentation, smoking, or other processes to enhance flavor or improve preservation. Common examples include bacon, sausage, hot dogs, ham, deli slices, and jerky. These meats are often high in sodium, saturated fat, and can contain chemical additives like nitrates and nitrites. Research links these components, along with potential carcinogens formed during processing or cooking, to increased risks of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers, even at low consumption levels.

Does this mean I can never eat processed meat again, or is a little bit okay?

Based on the large review published in Nature Medicine and supported by other research like the BMJ umbrella review on UPFs, there is no identifiable “safe” level of processed meat consumption, particularly concerning risks for type 2 diabetes and colorectal cancer. This suggests that even small amounts may increase risk over time. While occasional consumption might pose a lower risk than regular intake, the findings indicate a “monotonic increase,” meaning risk rises with any increased amount. Therefore, public health advice leans towards minimizing or ideally eliminating processed meat intake altogether for optimal health.

What are healthier protein sources I can eat instead?

Focus on protein sources that come in a healthier “package.” Excellent choices include plant-based proteins like beans (black beans, kidney beans, chickpeas), lentils, tofu, tempeh, nuts, seeds, and whole grains (like quinoa). These often provide fiber, vitamins, and minerals without the downsides of processed meats. If you include animal products, prioritize unprocessed options like fish (especially fatty fish like salmon), poultry (chicken, turkey without skin), and eggs. Moderation with lean red meat (like occasional lean beef) and unsweetened dairy can also fit into a healthy dietary pattern.

Conclusion

The latest comprehensive research strengthens the evidence against processed meat consumption. Findings indicating no “safe” level of intake for conditions like type 2 diabetes and colorectal cancer, even in small amounts, coupled with broader evidence linking ultra-processed foods to numerous health problems, send a clear message. While processed foods may offer convenience, prioritizing whole, unprocessed alternatives is the most impactful step you can take to protect your long-term health and reduce your risk of serious chronic diseases. Making conscious choices about your protein sources is a key part of building a healthier diet.

Word Count Check: 1050